No internet connection.

All search filters on the page have been cleared., your search has been saved..

- Sign in to my profile My Profile

A Case Study on Power and Politics in Organizations

- By: Florian Hemme & Marlene Dixon

- Publisher: Human Kinetics, Inc.

- Publication year: 2015

- Online pub date: January 02, 2018

- Discipline: Organizational Behavior , Sports Management

- DOI: https:// doi. org/10.1123/cssm.2014-0039

- Keywords: bases of power , boards of directors , organizations , parks , power with , sport management , staff Show all Show less

- Contains: Content Partners | Teaching Notes Length: 4,821 words Region: Global Originally Published In: Hemme , F. , & Dixon , M. ( 2015 ) A case study on power and politics in organizations . Case Studies in Sport Management , 4 ( 13 ), 99 – 106 . Industry: Sports activities and amusement and recreation activities Type: Indirect case info Online ISBN: 9781526432759 Copyright: © 2015 Human Kinetics, Inc. More information Less information

Teaching Notes

James Park has been hired as the new CEO by the board of directors of GoSports Inc., a large national sporting goods retailer, which has been battling economic and internal issues over the previous years. Despite Park’s experience at the helm of large companies in need of profound strategic and structural change, in his new position at GoSports he has been “butting heads” with a powerful collective of executives unhappy with the hire and threatened by the new CEO’s accolades. To complicate matters, rumor has it that the decision to hire Park was far from unanimous, with various factions vying for control in the company, waiting for a chance to fill the power vacuum a quick departure by Park would leave behind. After two weeks with the company, Park is called before the board of directors to report on the progress made and how he plans to return GoSports to its former glory.

Keywords : power, organizational behavior, organizational politics, organizational performance, group dynamics, conflict

Two weeks ago, James Park was hired as CEO of GoSports Inc., a major retailer for sporting goods and apparel in North America, operating over 300 stores in all 48 contiguous states. His task was to revitalize the company’s culture and breathe new life into the firm’s stagnant operations. However, soon after he started his new job in high spirits, Park realized that a handful of longtime executives were unhappy with his hire and, apparently threatened by the new CEO’s accolades, resisted every idea for change. Additionally, various department heads believed that strengthening their respective divisions was the preferred way for turning around the company; some even actively attempted to subvert Park’s revitalization efforts by withholding information, lobbying against him, and instructing their subordinates to “keep doing what we have always done.”

Park knew he was under close scrutiny to show results, as the board of directors had made it clear that they expected him to live up to his reputation – and the generous signing bonus. To complicate matters, rumor had it that the decision to hire Park had been far from unanimous. In fact, various factions inside GoSports (including some inside the board of directors) were vying for control in the company, hoping Park would not last long.

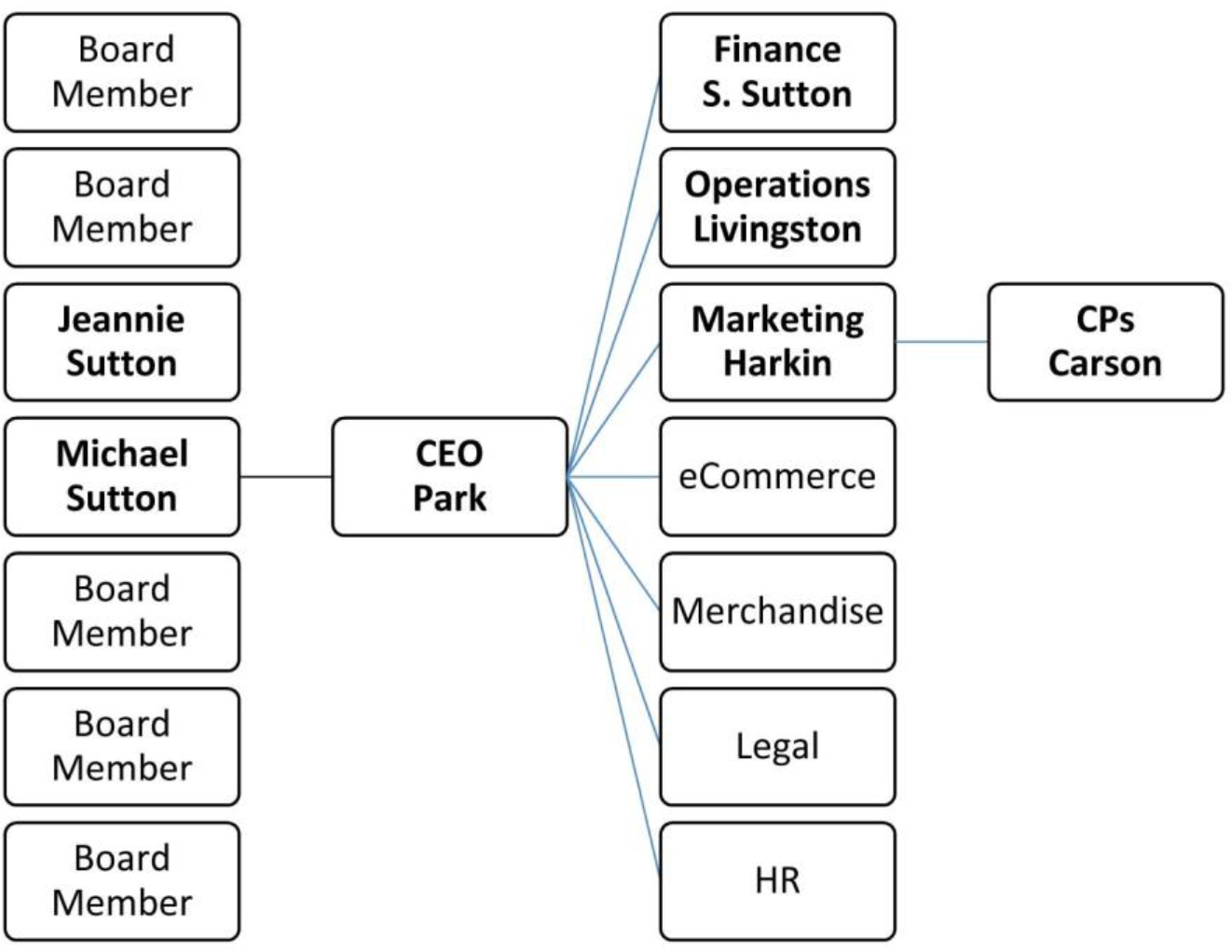

GoSports Inc. and the Sporting Good Retail Industry

GoSports Inc. was founded in 1973 and quickly grew from a small neighborhood store to a national chain. Headquartered in Philadelphia, PA, the Fortune 500 corporation provided customers with equipment for any sport, ranging from weight training to fishing. With this diverse product range came increased pressure to maintain a lean operation, and at the same time be able to meet consumer demand at the lowest inventory possible. After the original founder, Edward Sutton, had passed away, his three children took over the company. The oldest, Michael, and youngest, Jeannie, were members of the board, whereas the middle sister, Sarah, was director of finance. Most executives and high-ranking managers had been with the company for a long time and worked their way up from the inside ( Figure 1 ). In fact, most of them were from the greater Philadelphia area and had started as seasonal employees during high school. GoSports valued consistency and familiarity and most of the senior management shared personal interests and hobbies. At the same time, management at GoSports largely ruled by authority, emphasis on hierarchy, and favoritism. To complicate matters, there had been repeated disagreements over the years regarding the strategic direction of the company, with varying coalitions attempting to steer GoSports in one direction or another. These battles for internal control had not gone unnoticed, and mid- and low-level management had grown increasingly wary of being caught in the upper echelon’s power plays.

Over the past few years, GoSports had experienced a substantial decline in sales and revenue. Although part of these losses could be attributed to the overall shift toward online retailing, which favored smaller, specialized operations with less overhead, the downturn was in large part due to a series of missed opportunities and slow reactions to changing market conditions. GoSports’ management had proven unable to react to decreased foot traffic at physical stores and changing consumer preferences. Persistent disagreements and personal issues stymied effective decision making at the company. Competitors had seized on GoSports’ inability to evolve and had managed to capture significant market share. As numbers continued to deteriorate, the majority of the board of directors decided the company would benefit from an outside executive to revitalize the former industry leader and had pushed for the hire of Park. While shareholders and employees welcomed the bold move, it was unusual for GoSports to forsake its long-standing tradition of filling upper executive positions solely from within ( Figure 1 ).

Figure 1. Organizational chart

Charming and charismatic, with a certain penchant for flashiness, Park was well known in the industry for his ability to develop long-lasting relationships, spot trends, and quickly exploit opportunities. Born and raised in San Francisco, he attended Stanford University and launched his own sports and event management company in Los Angeles during his senior year of college. He eventually sold it to his partners after they had been able to establish the company as one of the most innovative and well-managed firms in the industry. His success in the highly competitive entertainment capital of the world made him a premier target for corporate headhunters and he eventually moved into a mid-level executive position with one of North America’s largest sporting goods manufacturers. During his ensuing 17-year tenure, Park quickly rose through the ranks and was integral in revitalizing the company, turning it into a multi-billion dollar business. During that time, Park spent several years working in Europe and Asia, where he still maintained many connections.

Park possessed an astute ability to understand people’s needs and desires and to gather support for his ideas and was known to quickly deal with those trying to stymie his efforts to guide his companies in a better direction. While lower and mid-level management often admired him for his approachable demeanor and honesty, fellow high-level executives had in public referred to him as a “shark” after Park had successfully pushed for organizational change against their will. At GoSports, the 45-year old Park, replaced 67-year old H. Grimm, who had been with the company for close to 35 years. The younger employees at GoSports welcomed the addition of Park, as many felt that over the years, seniority and personal connections had taken precedence over hard work, creativity, and merit. Many were excited about the fresh blood and the new vision Park brought with him.

The First Day

On his first day in the office, Park made it a point to walk around, shake hands, and to get to know employees of all ranks. Immediately, people noticed how different his warm and approachable presence was from Park’s predecessor and the cabal of current upper management. One of GoSports’ key account managers later commented, “You can tell he has been around the block a few times. His entire demeanor is different; he knows what he is talking about. I think he will be great for us, especially with all of his international experience.” After speaking with a group of executive assistants, one of them was particularly impressed by Park’s personable nature. She said, “What a charming guy! He seemed genuinely interested in what people had to say. When I ran into him a little later in the day, he even remembered my name.” Park even took the time to comment on one of the technology managers’ wall art. “I have had that Phillies mural for years now and none of the other managers has ever said anything. We chatted about baseball for a couple of minutes; he seems like a great guy.”

Later that day, Park gave a speech at a “town hall” meeting, the first in company history. Park planned on making these meetings a regular staple of corporate communication and employee involvement, just like he had done at his previous employer. His speech was emphatic, passionate, and left an instant impression with most of the employees.

It is an incredible honor to be here today to address you, my team, as your new CEO. First, I would like to thank the board of directors for putting their trust in me and for the opportunity to be part of a great organization. I would also like to thank all of you for the warm welcome you have given me this morning. I already have had the chance to speak to many of you and I hope that I will be able to meet everybody over the next couple of weeks. Today marks the beginning of a new era here at GoSports and I would like all of you to be a vital part of the process, for without you there is no GoSports and without your contribution we cannot succeed. It is my first day at work and I want nothing more than to get started, so let me keep this brief. GoSports faces a great number of challenges. But with those challenges come opportunities, opportunities we will seize to our fullest advantage. You already have an experienced management team that has been weathering the storm with you and now it is time to take matters back in our own hands, assume responsibility for our actions, and take GoSports back to where it belongs, the top. I pledge that I will always be available to every single one of you for your concerns, ideas, and feedback. We will broaden our channels of communication and encourage your creativity and your input. Later today, I will meet with your management team to plan our next steps. You will be kept informed during all stages of the process and your concerns will be taken into account. You are the power behind the changes we will have to make and I look forward to walking this path with you.

Park felt elated after that brief speech. He could tell that people liked what they had heard. During the speech, he had noticed several people nodding their head approvingly and a couple of employees approached him afterward expressing their personal welcome. GoSports’ employees appeared to take a lot of ownership of their company and their work. Park hoped to turn their attachment into a willingness to make personal sacrifices for the company. Unfortunately, things turned for the worse later that day when Park met with the rest of the executives. Among them was Luc Livingston, director of Operations at GoSports and heir apparent to the throne before the board had decided on Park as the new CEO; Betty Carson, director of Corporate Partnerships and Development; and Robert Harkin, director of Marketing. Also present was Director of Finance Sarah Sutton, as well as Michael and Jeannie Sutton. Park was scheduled to meet with the remaining board members the following week. While the majority of the employees and mid-level managers had given Park a warm welcome, the atmosphere at the executive meeting was frosty. Livingston opened the discussion by remarking sarcastically, “That was quite the speech you gave there. You better have a good secretary, now that you gave everybody permission to talk to you at all times of the day. People better still work and not spend their hours running to you with ludicrous suggestions.”

During the meeting, although never openly questioning Park’s suitability to run GoSports, Livingston had remained distant and dismissive, almost abrasive. Despite Park’s attempts to keep the conversation upbeat and professional, the director of Operations appeared to harbor ill will, making petty attempts to show how much more he deserved Park’s job. At one point during the meeting he remarked, “Why don’t you let us fill you in about how things are done here at GoSports? I am sure you had your way of running business in your previous position, just like we do here. After all, most of us have been here a long time. Well, except Sarah, she is still learning, too.” Park, not willing to muddy the waters on his very first day, politely replied by quickly covering some of his past work and then swiftly steering the conversation toward GoSports and the challenges ahead. He sensed that little would come out of having a group meeting, which Livingston would undoubtedly attempt to dominate, and suggested to meet with the other executives and board members individually.

Meeting with Luc Livingston

Luc Livingston, director of Operations, had started out at GoSports as a seasonal employee during high school and interned at the company’s headquarters during summers while attending the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. He had joined GoSports after graduating with highest honors and had quickly put his mark on the company’s operations. While he could be amicable when things were going well, he was known to have a short temper when waters were rough. He was incredibly skilled at navigating office politics, which enabled him to strike up beneficial relationships with a number of high-ranking executives early in his career. Under the tutelage of Howard Grimm and the protection of Michael Sutton, Livingston had been groomed to succeed Grimm whenever the time was right. He was extremely hungry for power and he had been enraged when he found out that he had been passed over for the job of CEO. He vowed to show everybody that the board had been pushed to make the wrong decision. He was planning to play along with the hiring of Park, but had already begun thinking about ways to ensure the new CEO’s quick failure. Unbeknownst to Michael Sutton, Livingston ultimately desired to be chairman of the board and viewed the CEO spot merely as a stepping stone to that position.

As Park had expected, Livingston provided little to no constructive information during their meeting. However, he was not foolish enough to blatantly question Park’s authority or overtly express his anger about not being chosen by the board to become the new CEO. Rather, he spent most of the time touting the achievements of his department, highlighting his own role in previous successes, and his long history with GoSports:

You see, James, I have been here a long time and I have been fortunate to work with a number of great people. But let me tell you, I have also seen people fail quickly because they didn’t understand our culture. We are a big family here and many of us have started from the very bottom and earned our way up. That kind of dedication and commitment is what has made us so successful and it will be key in our continued success. For example, when I started here all those years ago, we didn’t know the first thing about operations and how to run a company. Now, well, I built that success. GoSports needs someone in charge like that; someone who understands its strengths and weaknesses, someone who understands what it’ll take to focus on the right parts of the equation.

Meeting with Michael Sutton

The oldest of the three Suttons, Michael had always been a part of GoSports. He had no immediate interest in becoming involved with the actual business side of the company, but enjoyed playing politics and controlling things from behind the scenes as chairman of the board, a position he effectively inherited from his father. As the founder’s oldest son, Michael felt that everybody in the company owed him respect and reverence, and he was still angered that his sister had managed to convince the board to hire an outsider. While no one at GoSports questioned his commitment to the company and his desire to bring it back to former glory, few were convinced that Sutton spent enough time actually involving himself in the details of running a successful operation. Furthermore, his close ties with some of the executives made it hard for the board to remain independent and provide the checks and balances needed to control the CEO and ensure that shareholder interests were being maintained.

The meeting with Michael Sutton on the following day solidified Park’s first impression of the chairman. Even though Sutton was jovial, he made no secret of the fact that he would have favored Livingston to succeed Grimm, rather than hiring an outsider. He repeatedly alluded to Park’s limited knowledge of “how things work” at GoSports and made it a point to downplay many of the issues that plagued the company. Park could surmise that Sutton had spent little time in the past actually paying attention to what was going on in the industry. At one point Sutton remarked, “I can’t possibly keep up with every single detail. I have a lot of contacts, people talk to me all the time, and come to me for advice and to introduce them to others. I expect things to work the way they should without me looking over people’s shoulders all the time. After all, they know who they are ultimately working for.”

Most surprisingly, despite Park’s plans to meet with board members and executives individually, Jeannie Sutton, the chairman’s sister and youngest daughter of the deceased company founder, was also present. Noting Park’s surprise, she explained that her brother had asked her to attend so that the new CEO could get a better understanding of “what the family expects from him.” Jeannie Sutton was not involved in the company’s business beyond her role as board member and had historically backed her brother, whom she adored, in important decisions, believing he knew what would be best for the company. Much like her sister Sarah, however, Jeannie had grown wary of Michael’s bullish boardroom tactics. She was also suspicious of the concentration of power in the hands of a few, mostly male, individuals and had begun to wonder whether the extremely centralized decision-making process should be abandoned for a more open and inclusive approach.

Additionally, as Michael Sutton repeatedly pointed out, Jeannie had supported her sister Sarah’s push for hiring Park, indebting her to her brother to “at least show a united front once the new CEO gets here.” She seemed agreeable enough, yet Park sensed that she was caught in the power struggles between her siblings. She appeared guarded and did not volunteer much information as to the direction in which she wanted to see the company head. On two occasions, her brother interrupted her attempts to answer Park’s questions, after which she stayed quiet for the remainder of the conversation.

At one point during the conversation, which was rather a monologue by Sutton, the chairman had talked about his deceased father, the founder of GoSports:

You know, my father was a great man; he built this company from nothing, right here in Philadelphia. But there are things he could have done differently. He lacked the vision to really take this organization to the next level, take risks, be bold. There may have been some hiccups but I still believe we are on the right track. I have been working hard with director Livingston to position us well with regards to our competitors and I really hope that you have what it takes to continue down that path. I really suggest you work closely with him, let him show you the ropes. He has been with us for a long time and he knows what it takes to succeed, both here at GoSports and in this industry.

Park refrained from taking the bait, knowing full well that Livingston had been the one groomed to be next in line for the CEO position. Instead, he steered the conversation toward what appeared to be calmer waters, outlining some of his ideas to improve GoSports’ operations and bottom line. Sutton found fault with most of them and repeatedly told Park that “that won’t work with us here at GoSports.” Trying not to let his frustration show, Park left the meeting with a sense of foreboding. He knew then that working with the chairman of the board would not turn out to be as easy as he had hoped.

Meeting with Betty Carson

Betty Carson had joined GoSports after graduating from the University of Pittsburgh. The native Philadelphian was responsible for negotiating philanthropic support, sponsorships, and cause marketing efforts. Due to her position, she had access to a vast network of contacts in the industry. Additionally, she was very active in the local community and had recently begun pushing for GoSports to start a formally structured community volunteer program that would require employees of all ranks to engage with local schools, youth and children’s organizations, and animal shelters. Reactions to her efforts had been mixed, with most of her fellow senior executives outright rejecting the notion that they should be working alongside their subordinates. She was unsure how she felt about an outsider being chosen to become CEO, but also believed that GoSports’ culture had long been deteriorating. In her opinion, fresh blood might benefit the company and she was also hoping to interest the new CEO in her volunteer project.

Carson appeared to be elated to meet individually with Park. After the obligatory small talk, she steered the conversation toward her volunteer project. She told Park about the lack of support she had received for it, mostly because Livingston and Sutton had quickly denounced the merit of it and others had not considered it important enough to challenge the two men’s authority. Despite her challenges to get her project off the ground, Carson appeared to arguably be the most connected of all the executives. She provided Park with several anecdotes that involved members from all levels at GoSports and outside the company.

Meeting with Robert Harkin

Director of Marketing Robert Harkin had been with the company for over 20 years. He was a longtime confidant of Livingston, Grimm, and Michael Sutton, a member of the “old boys’ network” that had been running the company for over two decades. Despite his close relationships with the other men on the executive floor, though, Harkin believed that the time had come to initiate drastic change if the company wanted to survive. The current economic environment and changing consumption habits required emphasis on different aspects of the daily business than a decade ago. Harkin was under no illusion that GoSports had missed a number of exits on the road to continued and sustained competitive excellence. Furthermore, he had always tried to put the company’s best interests before personal feelings and relationships. Many employees considered him to be the most approachable of the male upper echelon and the people in his department admired him for his creative genius. While his connections with Livingston and Grimm had been extremely beneficial for his own career, he did not believe that Livingston was suitable to run a company like GoSports. Harkin also recently had begun to question the way that Michael Sutton threw his weight around without actually contributing to GoSports’ success. Overall, while he distrusted the outsider Park, he felt that the alternative would be even worse.

Harkin was enigmatic during the meeting with the new CEO. He talked at length about the deceased founder of the company, a man he admired for his tenacity and creativity. Park sensed that Harkin felt a deep sense of loyalty to GoSports as an organization rather than to the people currently in charge. When Park asked about his vision for the company, Harkin had evaded the question. He said, “We will always need creative people, people that have the guts to do big things, things that have not been done yet. I do not know what the future holds but I know that we as an organization may have to change a few things around if we want to succeed.” Leaving Harkin’s office, Park noticed a number of plaques, photographs, and framed awards on what appeared to be a department wall of fame. Harkin was in some of the pictures but most seemed to show other members of the department, often in groups, celebrating previous successes.

Meeting with Sarah Sutton

Sarah Sutton had only recently joined GoSports, after having worked for a number of financial consulting firms. After her father had passed, she initially had shown little interest in working for the company, but the recent issues and constant, at times public, disagreements had prompted her to abandon her career and join GoSports. She was concerned about her father’s legacy and felt that her siblings were doing too little to rectify the situation. She was particularly worried about her brother Michael being too close to Luc Livingston, whom she distrusted. As director of finance and a member of the founding family, Sarah had successfully pushed the board toward hiring an outsider to replace Howard Grimm as CEO. In her short time at the company, she had been able to improve the bottom line by imposing tighter budgets and forcing departments to operate more efficiently. She was well liked and respected for her past as a financial consultant and many of the female employees welcomed the fact that GoSports finally had a woman in charge of a department as pivotal as finance.

Sutton had warmly welcomed Park into her spacious office decorated with several diplomas and tasteful paintings. Park also noticed a number of awards the director had received during her previous career as a financial analyst and consultant. She cut right to business, asking Park how his meeting with her siblings had gone. Park was unsure how to answer. He sensed that Sarah Sutton could be a powerful ally but she was also the chairman’s sister. Equivocally, he offered, “Your brother seems to care a great deal about this company.” She pondered his response for a moment and answered, “He does. Unfortunately, he has no idea what he is doing and decided to back somebody who will eventually run this company into the ground.” Taken aback, Park asked who she was talking about and Sutton spent the rest of the time warning Park about Luc Livingston. She concluded their meeting by telling Park to make sure to get the right people on board with his revitalization efforts:

There are a number of great individuals here at GoSports, people that care deeply about this organization and that are very worried about the direction this organization has taken. Unfortunately, old habits and structures are hard to dissolve and re-develop for the better. You will be able to count on my support and that of many others but be prepared to run into problems. Most of the executives have been here a long time and none of them will be too thrilled about having their roles diminished.

Park thanked her for her advice, but at that point began to question his choice of taking the job. He had heard from several of his contacts in the industry that GoSports needed a profound change in corporate culture but he had not expected the situation to be this dire.

Meeting the Other Executives

Over the course of the next week, Park also met with the other executives and was able to gather valuable information about the company and its culture. He learned about the icy relationship between Livingston and Harkin—the former jealous of the other’s creativity and personal relationships with his peers, and the latter increasingly frustrated with having to work with someone who did not seem to put the company’s well-being before his own personal agenda. Park further noted a great deal of frustration among some of the other executives who did not form part of the inner circle.

The Present Day

Today, two weeks after being named CEO of GoSports, Park had been summoned to report to the board of directors his plans to turn the company around. He knew what he had to do in order to take GoSports not only back to its former place atop the industry, but also to unknown spheres yet untapped. He had formulated a strategy that involved the participation of key members of the executive team, as well as widespread support from mid- and lower-level employees. He knew it would not be easy. His pitch to the board had to be perfect, his arguments sound, and his rhetoric convincing. He straightened his tie, grabbed his notes, and headed into the meeting.

Discussion Questions

- 1. What is the main issue described in the case?

- 2. Who are the competing individuals/factions?

- 3. Using French and Raven’s (1959; see also Raven, 1959, 1965, 1992) extended power taxonomy, identify different power sources used and the people who use them. Individuals may use more than one power source.

- 4. Identify and analyze the problems created between organizational members due to uses of power.

- 5. Analyze the potential motivations behind particular uses of power.

- 6. Who would you identify as the most powerful individual in the case? Why?

Literature Cited

This case was prepared for inclusion in Sage Business Cases primarily as a basis for classroom discussion or self-study, and is not meant to illustrate either effective or ineffective management styles. Nothing herein shall be deemed to be an endorsement of any kind. This case is for scholarly, educational, or personal use only within your university, and cannot be forwarded outside the university or used for other commercial purposes.

2024 Sage Publications, Inc. All Rights Reserved

Sign in to access this content

Get a 30 day free trial, more like this, sage recommends.

We found other relevant content for you on other Sage platforms.

Have you created a personal profile? Login or create a profile so that you can save clips, playlists and searches

- Sign in/register

Navigating away from this page will delete your results

Please save your results to "My Self-Assessments" in your profile before navigating away from this page.

Sign in to my profile

Please sign into your institution before accessing your profile

Sign up for a free trial and experience all Sage Learning Resources have to offer.

You must have a valid academic email address to sign up.

Get off-campus access

- View or download all content my institution has access to.

Sign up for a free trial and experience all Sage Learning Resources has to offer.

- view my profile

- view my lists

- For educators

- English (US)

- English (India)

- English (UK)

- Greek Alphabet

This problem has been solved!

You'll get a detailed solution from a subject matter expert that helps you learn core concepts.

Question: Read the Organizational Power and Politics case study on pages 174-175 of your text. Let's begin by discussing the first question: (a)What source of power does Helen have, and (b) what type of power is she using? (c) Which influencing tactic is Helen using during the meeting? (d) Is negotiation and/or the (e) exchange tactic appropriate in this situation?

(a) Source of Power : To determine Helen's source of power, you would need to look at the information...

Not the question you’re looking for?

Post any question and get expert help quickly.

Power and politics in organizations

Cite this chapter.

- Liz Fulop ,

- Stephen Linstead &

- Faye Frith

246 Accesses

3 Citations

In the UK in the late 1980s, many polytechnics were about to become universities, of which Fairisle Polytechnic was one. At this time, however, they were still under the control of local authorities and they still provided non-advanced further education (NAFE) course — work of sub-degree standard. It was becoming clear that this level of work was regarded by the government as the province of the local authority institutions. It would only be left in the hands of the new universities if there was no alternative local provider, and in Fairisle there were several competent others. It followed that any site which was designated a NAFE site by the Asset Commission would revert to the local authority when they decided on the terms of separation, i.e. ‘divorce and alimony’. Fairisle currently occupied as one of its many sites a campus at Fawley Ridge, an area of prime residential land, rapidly appreciating in value and conservatively estimated to be worth at contemporary prices around £1.5 million as a piece of land alone. The new university would need such an asset given its desperate need for building space — but the site was almost exclusively NAFE, being devoted to evening classes in a huge range of languages and providing daytime courses for local business people. Only the highest level of linguistic qualification offered was regarded officially as being ‘advanced’ for funding purposes — and this was only 5 percent of the total workload.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Similar content being viewed by others

The More American Sociology Seeks to Become a Politically-Relevant Discipline, the More Irrelevant it Becomes to Solving Societal Problems

Strange Bedfellows: Austerity and Social Justice at the Neoliberal University

The Role of Shadow Organizing in Dealing with Overflows of Knowledge and Ambition in Higher Education

Anthony, P (1994) Managing Culture Buckingham: Open University Press.

Google Scholar

Bacharach, S. and Baratz, M.S. (1962) ‘Two faces of power’, American Political Science Review 56(4), November 947–52.

Bailey, F.G. (1970) Strategems and Spoils, Oxford: Blackwell.

Barbalet, J.M. (1986) ‘Power and resistance’, British Journal of Sociology 36(1): 521–48.

Blake, R. and Mouton, J. (1978) The New Managerial Grid , Houston: Gulf

Bolman, L.G. and Deal,T.E. (1991) Reframing Organizations:Artistry, Choice and Leadership, San Francisco: JosseyBass.

Buchanan, D. and Badham, R. (1998) Winning the Game : Power, Politics, and Organizational Change , London: Paul Chapman.

Burrell, G. and Morgan, G. (1979) Sociological Paradigms and Organisational Analysis, London: Gower.

Burrell, G. (1988)’Modernism, postmodernism and organization studies 2: The contribution of Michel Foucault’, Organization Studies 9(2): 221–35.

Article Google Scholar

Burton, C. (1987) ‘Merit and gender: Organisations and mobilisations of masculine bias’, Australian Journal of Social Issues 22(2): 424–49

Burton, C. (1991) The Promise and the Price:The Struggle for Equal Opportunity in Women’s Employment , Sydney: Allen and Unwin.

Byrt,W.J. (1973) Theories of Organisation , Sydney: McGraw-Hill.

Canetti, E. (1987) Crowds and Power, Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin.

Catalyst (1996) Women in Corporate Leadership: Progress and Prospects, NewYork: Catalyst.

Child, J. (ed.) (1973) Man and Organizations: The Search for Explanation and Social Relevance , London: Allen and Unwin.

Clegg, S.R. and Dunkerley, D. (1980) Organizations, Class and Control , London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Clegg, S.R. (1989) Frameworks of Power , London: Sage.

Book Google Scholar

Clegg, S.R. (1990) Modern Organizations: Organization Studies in the Postmodern World London: Sage.

Clegg, S.R. (1994) ‘Power relations and the constitution of the resistant subject’ in fermier, J., Nord, W. and Knights, D. (eds), Resistance and Power in Organizations: Agency, Subjectivity and the Labour Process, London: Routledge.

Coe,T. (1992) The Key to the Men’s Club , London: Institute of Management.

Collinson, D. (1994)’Strategies of resistance: Power, knowledge and subjectivity in the workplace’, in Jermier,,J., Nord, W. Knights, D. (eds), Resistance and Power in Organizations: Agency, Subjectivity and the Labour Process, London: Routledge.

Cooper, R.C. (1990) ‘Canetti’s sting’, SCOS Notework 9 (2/3): 45–53.

Crozier, M, (1964) The Bureaucratic Phenomenon Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Dahl, R. (1957) ‘The concept of power’, Behavioural Science 2 July: 201–15.

Dawson, S. (1986) Analysing Organisations, London: Macmillan.

Ely, R.J. (1995) ‘The power in demography: Women’s social construction of gender identity at work’, Academy of Management Journal 38: 589–634.

Forster, J. and Browne, M. (1996) Principles of Strategic Management , Melbourne: Macmillan.

French, J.R.P. and Raven, B. (1959) ‘The bases of social power’, in Cartwright, L. and Zander, A. (eds), Group Dynamics, Research and Theory , London: Tavistock.

Frith, F. and Fulop, L. (1992) ‘Conflict and power in organisations’, in Fulop, L. with Frith, F. and Hayward, H., Management for Australian Business:A Critical Text , Melbourne: Macmillan.

Fulop, L. (1992) ‘Bureaucracy and the Modern Manager’, in Fulop, L. with Frith, F. and Hayward, H., Management forAustralian Business:A Critical Text , Melbourne: Macmillan.

Glazer, M.P. and Glazer, PM, (1989) Whistle-Blowers : Exposing Corruption in Government and Industry , New York: Basic Books.

Goffman, E. (1979) GenderAdvertisements New York: Harper and Row.

Gollam, P. (1997)’Successful staff selection:The value of acknowledging women’, Management October: 25–6.

Gouldner,,A.W. (1954) Patterns of Industrial Bureaucracy New York:The Free Press.

Handy, C. (1985) Understanding Organizations (third edition), Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin.

Hardy, C. (1994) ‘Power and politics in organisations’, in Hardy, C. (ed.), Managing Strategic Action: Mobilizing Change , London: Sage.

Hardy, C. and Leiba-O’Sullivan, S. (1998) ‘The power behind empowerment: implications for research and practice’, Human Relations 15(4): 451–83.

Hickson, D.J. and McCullough,A.F. (1980) ‘Power in organizations’ in Salaman, G. and Thompson, K. (eds), Control and Ideology in Organizations , Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

Hickson, D.J., Hinings, C.R., Lee, C.A., Schneck, R.E. and Pennings,J.M. (1971) ‘The strategic contingencies theory of intraorganisational power’, Administrative Science Quarterly 16(2):216–29.

Jones, J.E. and Bearley, W.L. (1988) Empowerment Profile, King of Prussia, PA: Organization Design and Development.

Kanter, RM. (1977a) ‘Power games in the corporation’, Psychology Today July : 48–53.

Kanter, R.M. (1977b) Men and Women of the Corporation New York: Basic Books.

Kanter, R.M. (1979) ‘Power failure in management circuits’, Harvard Business Review 57 (4): 65–75.

Kanter, R.M. (1982) ‘The middle manager as innovator’, Harvard Business Review 60(4): 95–105.

Kanter, R.M. (I 983) The Change Masters: Innovation and Entrepreneurship in the American Corporation, New York: Simon and Schuster.

Kanter, R.M. (1989a) ‘Swimming in newstreams: Mastering innovation dilemmas’, California Management Review 31(4):45–69.

Kanter, R.M. (1989b) ‘The new managerial work’, Harvard Business Review 67(6): 85–92.

Kanter, R.M. (1989c) When Giants Learn to Dance: Mastering the Challenge of Strategy, Management and Careers in the I 990s , NewYork: Simon and Schuster.

Keys, B. and Case, T. (1990) ‘How to become an influential manager’, Academy of Management Executive 4: 38–51.

Kirkbride, P.S. (1985) ‘The concept of power: A lacuna in industrial relations theory?’, journal of Industrial Relations 27(3): 265–82.

Kotter,J. (1977) ‘Power, dependence, and effective management’, Harvard Business Review 55 (4): 125–36.

Knights, D. and Vurdubakis,T (1994) ‘Power, resistance and all that’, in Jermier,, J.M., Nord, W.R. and Knights, D. (eds), Resistance and Power in Organizations:Agency, Subjectivity and the Labour Process, London: Routledge.

Kram, K.E. (1985) Mentoring at Work, Glenview, III.: Scott, Foresman.

Lansbury, R.K. and Spillane, R. (1983) Organisational Behaviour in the Australian Context Melbourne: Longman Cheshire.

Linstead, S. (1997) ‘Resistance and return: Power, command and change management’, Studies in Cultures Organizations and Societies 3(1): 67–89.

Lukes, S. (1974) Power:A Radical View , London: Macmillan.

Maddock, S. and Parkin, D. (1994) ‘Gender cultures: How they affect men and women at work’, in Davidson, M. and Burke, R. (eds), Women in Management : Current Research Issues, London: Paul Chapman.

Margretta, J. (1997)’Will She Fit In?’, Harvard Business Review March—April: 18–32.

Marshall, J. (1995) Women Managers Moving On: Exploring Career and Life Choices , London: Routledge. Mauss, M. ( 1990 ) The Gift, London: Routledge.

McGregor, D. (1960) The Human Side of Enterprise, NewYork: McGraw-Hill.

Mechanic, D. (1962) ‘Sources of power of lower participants in complex organisations’, Administrative Science Quarterly 7: 349–64.

Mintzberg, H. (1983) Power In and Around Organisations Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Mintzberg, H. (1989) Mintzberg on Management: Inside Our Strange World of Organisations, New York and London: The Free Press.

Myers, D.W. and Humphreys, N.J. (1985) ‘The caveats in mentorship’, Business Horizons 28 (4): 9–14.

Pfeffer, J. (1981) Power in Organisations London: Pitman.

Pugh, D.S., Hickson, D.J. and Hinings, C.R. (1983) Writers on Organizations , Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin.

Ragins, B.R. (1997) ‘Diversified mentoring relationships in organizations: A power perspective’, Academy of Management Review 22 (2): 482–521.

Reed, M. (1985) Redirections in Organisational Analysis , New York: Tavistock.

Ryan, M. (1984) Theories of power’, in Kababadse, A. and Parker, C. (eds), Power, Politics, and Organisations:A Behavioural Science View , London: John Wiley.

Salaman, G. (1979) Work Organisations, Resistance and Control , London: Heinemann.

Silverman, D. (1970) The Theory of Organisations , London: The Open University.

Simpson, R. (1997) Have times changed? Career barriers and the token woman manager’, British Journal of Management (Special Issue) 8: 5121–30.

Velasquez, M. (1988) Business Ethics , Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Weber, M. (1964) The Theory of Social Economic Organization , London: Heinemann.

Whitley, W., Dougherty,T..W. and Dreher, G.F. (1991) ‘Relationship of career mentoring and socioeconomic origins to managers’ and professionals’ early career progress’, Academy of ManagementJournal 34: 331–51.

Download references

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Copyright information

© 1999 L. Fulop and S. Linstead

About this chapter

Fulop, L., Linstead, S., Frith, F. (1999). Power and politics in organizations. In: Management. Palgrave, London. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-15064-9_5

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-15064-9_5

Publisher Name : Palgrave, London

Print ISBN : 978-0-333-77632-2

Online ISBN : 978-1-349-15064-9

eBook Packages : Palgrave Business & Management Collection Business and Management (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

All Subjects

Power and Politics in Organizations

Study guides for every class, that actually explain what's on your next test, from class:.

A case study is a detailed analysis of a specific instance or example, often used to explore complex issues within real-world contexts. By examining a particular situation, case studies can reveal insights about power dynamics, leadership effectiveness, and organizational behavior, making them valuable tools for understanding how theory applies in practice.

congrats on reading the definition of Case Study . now let's actually learn it.

5 Must Know Facts For Your Next Test

- Case studies often involve multiple data sources such as interviews, observations, and archival records to provide a comprehensive view of the situation being analyzed.

- They are especially useful for exploring the relationship between leadership effectiveness and power dynamics in organizations.

- Case studies can highlight best practices and lessons learned from real-life scenarios, making theoretical concepts more relatable and applicable.

- Incorporating case studies into learning allows for critical thinking as students analyze the complexities of leadership and decision-making.

- They can also reveal the impact of contextual factors on organizational outcomes, demonstrating that one-size-fits-all solutions rarely apply in real-world situations.

Review Questions

- A case study provides a practical example that illustrates how different leadership styles can influence power dynamics within an organization. By analyzing a specific instance where leadership decisions directly impacted organizational outcomes, one can see the interplay between authority and influence. This approach allows for deeper insights into what makes leaders effective in various contexts.

- One strength of case studies is their ability to provide rich, contextual information that helps illuminate complex issues within organizations. They allow researchers to explore nuances that quantitative methods might overlook. However, a key weakness is that findings from a single case may not be generalizable to all situations, potentially limiting broader applicability. Additionally, the subjective nature of data collection and interpretation can introduce bias.

- By synthesizing findings from various case studies, one can identify common themes regarding effective leadership strategies across different contexts. For instance, several cases might reveal that transformational leadership consistently leads to higher employee engagement and better organizational outcomes. This synthesis allows for developing best practices that can guide future leaders in fostering positive environments while considering contextual variations.

Related terms

Qualitative Research : A research method focused on understanding the meaning behind human experiences, often involving interviews, observations, and case studies.

Leadership Styles : Different approaches that leaders use to motivate and guide their teams, including autocratic, democratic, transformational, and transactional styles.

Organizational Behavior : The study of how individuals and groups act within organizations, influenced by culture, structure, and the power dynamics present.

" Case Study " also found in:

Subjects ( 60 ).

- 2D Animation

- AP Human Geography

- AP Psychology

- Adolescent Development

- Adult Nursing Care

- Advanced Communication Research Methods

- Advanced Design Strategy and Software

- Advanced Editorial Design

- American Society

- Art Direction

- Art Therapy

- Business Anthropology

- Business Storytelling

- Causes and Prevention of Violence

- Communication Research Methods

- Comparative Criminal Justice Systems

- Contemporary Social Policy

- Crisis Management

- Curriculum Development

- Customer Insights

- Documentary Production

- Economic Development

- Economic Geography

- Educational Psychology

- Ethnic Studies

- Global Studies

- History of Education

- Human Storyteller

- Interest Groups and Policy

- Intro to African American Studies

- Intro to Comparative Politics

- Intro to Education

- Intro to Humanities

- Intro to Political Research

- Intro to Political Sociology

- Intro to Public Policy

- Intro to Sociology

- Investigative Reporting

- Journalism Research

- Leading Strategy Implementation

- Literacy Instruction

- Market Research Tools

- Mathematics Education

- Music Psychology

- Music of the Modern Era

- Organization Design

- Performance Studies

- Political Economy of International Relations

- Predictive Analytics in Business

- Professional Presentation

- Professionalism and Research in Nursing

- Social Problems and Public Policy

- Social Stratification

- Social Studies Education

- Sociology of Education

- Sociology of Marriage and the Family

- Sociology of Religion

- Special Education

- The Modern Period

© 2024 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.

Ap® and sat® are trademarks registered by the college board, which is not affiliated with, and does not endorse this website..

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

The 4 Types of Organizational Politics

- Michael Jarrett

The woods, the weeds, the rocks, the high ground.

Politics can become a dysfunctional force in organizations, but it can also be beneficial. To learn how to skillfully navigate organizational politics, managers first have to map the terrain. To do this, consider two questions: are you dealing with politics at the individual level or the enterprise level? And second, are you dealing with formal authority and structures or hidden, unspoken norms? Depending on the answers to these two questions, we end up with four different types of political terrain: “the weeds,” where personal influence and informal networks rule; “the rocks,” where power rests on individual interactions and formal sources of authority; the “high ground,” which combines formal authority with organizational systems; and “the woods,” or an organization’s implicit norms, hidden assumptions, and unspoken routines. Influential executives understand how to navigate all four terrains.

The first 100 days are usually the honeymoon period for any new CEO to make their mark and get others on board. However, for Airbus CEO Christian Streiff, it was just a brief window before his abrupt departure from the European aircraft company that’s part of the EADS consortium, along with DiamlerChrysler and Aerospatiale-Matra.

- MJ Michael Jarrett is a Senior Affiliate Professor in organizational behavior at INSEAD. Previously, Michael was a full-time faculty member at Cranfield School of Management, taught at London Business School, and consulted to companies on change management.

Partner Center

IMAGES

COMMENTS

This case was prepared for inclusion in Sage Business Cases primarily as a basis for classroom discussion or self-study, and is not meant to illustrate either effective or ineffective management styles. Nothing herein shall be deemed to be an endorsement of any kind.

Step 1. (a) Source of Power: To determine Helen's source of power, you would need to look at the information... Read the Organizational Power and Politics case study on pages 174-175 of your text. Let's begin by discussing the first question: (a)What source of power does Helen have, and (b) what type of power is she using?

4 Is everyone able to gain or exercise power in organizations? As with the previous chapters, we begin with a case study that sets the scene for discussing power and politics in organizations. The case study in this chapter is presented in two parts. Fawley Ridge In the UK in the late 1980s, many polytechnics were about to become universities ...

To answer this, we conducted a case study within a Fortune 250 company, Midwest Global Manufacturing (MGM), to explore the use of organizational politics for office-based employees and teleworkers. Our findings suggest that teleworkers strategically leverage the informal system to compensate for the lack of traditional social interaction to ...

individuals think of it rather than what it actually represents because. the higher the perceptions of politics are in the eyes of an organization. member, the lower in that person’s eyes is the ...

In Mintzberg’s (1983a; 1984; 2002) terms, the organization is a political arena, one in which the system of politics comes into play whenever the systems of authority, ideology, or expertise may be contested in various. CHAPTER 5 MANAGING POWER AND POLITICS IN ORGANIZATIONS 163. Image 5.3.

James Park has been hired as the new CEO by the board of directors of GoSports Inc., a large national sporting goods retailer, which has been battling economic and internal issues over the previous years. Despite Park’s experience at the helm of large companies in need of profound strategic and structural change, in his new position at GoSports he has been “butting heads” with a powerful ...

Case 13: A Case Study on Power and Politics in Organizations. Florian Hemme, M. Dixon. Published 29 December 2015. Business, Political Science. James Park has been hired as the new CEO by the board of directors of GoSports Inc., a large national sporting goods retailer, which has been battling economic and internal issues over the previous years.

A case study is a detailed analysis of a specific instance or example, often used to explore complex issues within real-world contexts. By examining a particular situation, case studies can reveal insights about power dynamics, leadership effectiveness, and organizational behavior, making them valuable tools for understanding how theory applies in practice.

And second, are you dealing with formal authority and structures or hidden, unspoken norms? Depending on the answers to these two questions, we end up with four different types of political ...