Help | Advanced Search

Astrophysics > Earth and Planetary Astrophysics

Title: revelations on jupiter's formation, evolution and interior: challenges from juno results.

Abstract: The Juno mission has revolutionized and challenged our understanding of Jupiter. As Juno transitioned to its extended mission, we review the major findings of Jupiter's internal structure relevant to understanding Jupiter's formation and evolution. Results from Juno's investigation of Jupiter's interior structure imply that the planet has compositional gradients and is accordingly non-adiabatic, with a complex internal structure. These new results imply that current models of Jupiter's formation and evolution require a revision. In this paper, we discuss potential formation and evolution paths that can lead to an internal structure model consistent with Juno data, and the constraints they provide. We note that standard core accretion formation models, including the heavy-element enrichment during planetary growth is consistent with an interior that is inhomogeneous with composition gradients in its deep interior. However, such formation models typically predict that this region, which could be interpreted as a primordial dilute core, is confined to about 10% of Jupiter's total mass. In contrast, structure models that fit Juno data imply that this region contains 30% of the mass or more. One way to explain the origin of this extended region is by invoking a relatively long (about 2 Myrs) formation phase where the growing planet accretes gas and planetesimals delaying the runaway gas accretion. Alternatively, Jupiter's fuzzy core could be a result of a giant impact or convection post-formation. These novel scenarios require somewhat special and specific conditions. Clarity on the plausibility of such conditions could come from future high-resolution observations of planet-forming regions around other stars, from the observed and modeled architectures of extrasolar systems with giant planets, and future Juno data obtained during its extended mission.

Submission history

Access paper:.

- Other Formats

References & Citations

- Google Scholar

- Semantic Scholar

BibTeX formatted citation

Bibliographic and Citation Tools

Code, data and media associated with this article, recommenders and search tools.

- Institution

arXivLabs: experimental projects with community collaborators

arXivLabs is a framework that allows collaborators to develop and share new arXiv features directly on our website.

Both individuals and organizations that work with arXivLabs have embraced and accepted our values of openness, community, excellence, and user data privacy. arXiv is committed to these values and only works with partners that adhere to them.

Have an idea for a project that will add value for arXiv's community? Learn more about arXivLabs .

The atmosphere of Jupiter

- Published: March 1976

- Volume 18 , pages 603–639, ( 1976 )

Cite this article

- Andrew P. Ingersoll 1

130 Accesses

2 Citations

Explore all metrics

Current information on the neutral atmosphere of Jupiter is reviewed, with approximately equal emphasis on composition and thermal structure on the one hand, and markings and dynamics on the other. Studies based on Pioneer 10 and 11 data are used to refine the atmospheric model. Data on the interior are reviewed for the information they provide on the deep atmosphere. The markings and dynamics are discussed with emphasis on qualitative relationships and analogies with phenomena in the Earth's atmosphere.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price excludes VAT (USA) Tax calculation will be finalised during checkout.

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Tenuous Atmospheres in the Solar System

Atmospheric Physics and Atmospheres of Solar-System Bodies

Aitken, D. K. and Jones, B.: 1972, Nature (London) 240 , 230.

Google Scholar

Anderson, J. D., Hubbard, W. B., and Slattery, W. L.: 1974a, Astrophys. J. 193 , L149.

Anderson, J. D., Null, G. W., and Wong, S. K.: 1974b, J. Geophys. Res. 79 , 3661.

Armstrong, K. R., Harper, D. A., Jr., and Low, F. J.: 1972, Astrophys. J. 178 , L89.

Aumann, H. H., Gillespie, C. M., Jr., and Low, F. J.: 1969, Astrophys. J. 157 , L69.

Baker, A. L., Baker, L. R., Beshore, E., Blenman, C., Castillo, N. D., Chen, Y.-P., Doose, L. R., Elston, J. P., Fountain, J. W., Gehreis, T., Kendall, J. H., KenKnight, C. E., Norden, R. A., Swindell, W., Tomasko, M. G., and Coffeen, D. L.: 1975, Science 188 , 468.

Barcilon, A. and Gierasch, P. J.: 1970, J. Atmospheric Sci. 27 , 550.

Bar-Nun, A.: 1975, Icarus 24 , 86.

Böhm, K.-H.: 1967, in R. N. Thomas (ed.), ‘Aerodynamic Phenomena in Stellar Atmospheres’, IAU Symp. 28 , 366.

Brinkmann, R. T.: 1974, Nature (London) 230 , 515.

Busse, F. H.: 1970, Astrophys. J. 159 , 629.

Busse, F. H.: 1975, Paper presented at the Jupiter Conference, Tucson, Arizona, May 19–23, 1975.

Cameron, A. G. W.: 1973, Space Sci. Rev. 14 , 392.

Carlson, R. W. and Judge, D. L.: 1974, J. Geophys. Res. 79 , 3623.

Carr, T. D.: 1971, Astrophys. Letters 7 , 157.

Chapman, C. R.: 1969, J. Atmospheric Sci. 26 , 986.

Chase, S. C., Ruiz, R. D., Münch, G., Neugebauer, G. Schroeder, M., and Trafton, L. M.: 1974, Science 183 , 315.

Divine, N.: 1971, ‘The Planet Jupiter (1970)’, NASA Space Vehicle Design Criteria (Environment), NASA SP-8069, Dec.

Duncombe, R. L., Kepczynski, W. J., and Seidelmann, P. K.: 1973, Fundamentals Cosmic Phys. 1 , 119.

Elliot, J., Wasserman, L., Veverka, J., Sagan, C., and Liller, W.: 1974, Astrophys. J. 190 , 719.

Flasar, F. M.: 1973, Astrophys. J. 186 , 1097.

French, R. G. and Gierasch, P. J.: 1974, J. Atmospheric Sci. 31 , 1707.

Gierasch, P. J.: 1973, Icarus 19 , 482.

Gierasch, P. J. and Goody, R. M.: 1969, J. Atmospheric Sci. 26 , 979.

Gierasch, P. J., Ingersoll, A. P., and Williams, R. T.: 1973, Icarus 19 , 473.

Gillett, F. C. and Westphal, J. A.: 1973, Astrophys. J. 179 , L153.

Gillett, F. C., Low, F. J., and Stein, W. A.: 1969, Astrophys. J. 157 , 925.

Graboske, H. C., Jr., Pollack, J. B., Grossman, A. S., and Olness, R. J.: 1975, Astrophys. J. , in press.

Gulkis, S.: 1973, Space Sci. Rev. 14 , 497.

Gulkis, S. and Poynter, R.: 1972, Phys. Earth Planetary Interiors 6 , 36.

Gulkis, S., Klein, M. J., and Poynter, R. L.: 1974, in A. Woszeryk and C. Iwaniszewska (eds.), ‘Exploration of the Planetary System’, IAU Symp. 65 , 367.

Henry, R. J. W. and McElroy, M. B.: 1969, J. Atmospheric Sci. 26 , 912.

Hess, S. L. and Panofsky, A. A.: 1951, in Compedium of Meteorology , American Meteorological Society, Boston, p. 391.

Hide, R.: 1961, Nature (London) 190 , 895.

Hide, R.: 1963, Mem. Soc. Roy. Sci. Liège (Series) V VII , 481.

Hide, R.: 1966, Planetary Space Sci. 14 , 669.

Houck, J., Pollack, J. B., Schack, D., and Reed, R.: 1974, Amer. Astron. Soc., 5th Annual Meeting, Palo Alto, Ca.

Howard, H. T., Tyler, G. L., Fjeldbo, G., Kliore, A. J., Levy, G. S., Brunn, D. L., Dickinson, R., Edelson, R. E., Martin, W. L., Postal R. B., Seidel, B., Sesplaukis, T. T., Shirley, D. L., Stelzried, C. T., Sweetnam, D. N., Zygielbaum, A. I., Esposito, P. B., Anderson, J. D., Shaprio, I. I., and Reasenberg, R. D.: 1974, Science 183 , 1298.

Hubbard, W. B.: 1969, Astrophys. J. 155 , 333.

Hubbard, W. B.: 1970, Astrophys. J. 162 , 687.

Hubbard, W. B.: 1973, Space Sci. Rev. 14 , 424.

Hubbard W. B. and Smoluchowski R.: 1973, Space Sci. Rev. 14 , 599.

Hubbard, W. B., and VanFlandern, T. C.: 1972, Astron. J. 77 , 65.

Hubbard, W. B., Hunten, D. M., and Kliore, A.: 1975, Astrophys. J. , in press.

Hubbard, W. B., Nather, R. E., Evans, D. S., Tull, R. G., Wells, D. C., van Citters, G. W., Warner, B., and Vanden Bout, P.: 1972, Astron. J. 77 , 41.

Hubbard, W. B., Trubitsyn, V. P., and Zharkov, V. N.: 1974, Icarus 21 , 147.

Hunten, D. M. and Münch, G.: 1973, Space Sci. Rev. 14 , 433.

Ingersoll, A. P.: 1973, Science 182 , 1346.

Ingersoll, A. P.: 1975, Paper presented at Jupiter Conference, Tucson, Arizona, May 19–23, 1975.

Ingersoll, A. P. and Cuzzi, J. N.: 1969, J. Atmospheric Sci. 26 , 981.

Ingersoll, A. P., Münch, G., Neugebauer, G., Diner, D. J., Orton, G. S., Schupler, B., Schroeder, M., Chase, S. C., Ruiz, R. D., and Trafton, L. M.: 1975a, Science 188 , 472.

Ingersoll, A. P., Münch, G., Neugebauer, G., and Orton, G. S.: 1975b, Paper presented at Jupiter Conference, Tucson, Arizona, May 19–23, 1975.

Keay, C. S. L., Low, F. J., Rieke, G. H., and Minton, R. B.: 1973, Astrophys. J. 183 , 1063.

Khare, B. N. and Sagan, C.: 1973, Icarus 20 , 311.

Kieffer, H. H.: 1967, J. Geophys. Res. 72 , 3179.

Kliore, A., Fjeldbo, G., Seidel, B. L., Sesplankis, T. T., Sweetnam, D. W., Woiceshyn, P. M.: 1975, Science 188 , 474.

Larson, H. P., Fink, U., Treffers, R., Gautier, T. N.: 1975, Astrophys. J. , in press.

Lewis, J. S.: 1969, Icarus 10 , 365.

Lewis, J. S.: 1973, Space Sci. Rev. 14 , 401.

Lewis, J. S. and Prinn, R. G.: 1970, Science 169 , 472.

Maxworthy, T. and Redekopp, L. G.: 1975, Paper presented at Jupiter Conference, Tucson, Arizona, May 19–23, 1975.

McElroy, M. B.: 1973, Space Sci. Rev. 14 , 460.

Molton, P. M. and Ponnamperuma, C.: 1974, Icarus 21 , 166.

Murphy, R. E. and Fesen, R. A.: 1974, Icarus 21 , 42.

Newburn, R. L., Jr. and Gulkis, S.: 1973, Space Sci. Rev. 14 , 179.

Newburn, R. L., Jr. and Gulkis, S.: 1975, in Foundations of Space Biology and Medicine Vol. I , part 2, ch. 3, NASA Office of Life Science, Washington, D. C.

Ohring, G.: 1973, Astrophys. J. 184 , 1027.

Orton, G. S.: 1975a, Icarus , in press.

Orton, G. S.: 1975b, Paper presented at Jupiter Conference, Tucson, Arizona, May 19–23, 1975.

Orton, G. S.: 1975c, Icarus , in press.

Orton, G. S.: 1975d, Icarus , in press.

Owen, T. and Mason, H. P.: 1969, J. Atmospheric Sci. 26 , 870.

Palmén, E. and Newton, C. W.: 1969, Atmospheric Circulation Systems , Academic Press, New York and London.

Peek, B. M.: 1958, The Planet Jupiter , Faber and Faber, London.

Pilcher, S. B., Prinn, R. B., and McCord, T. B.: 1973, J. Atmospheric Sci. 30 , 302.

Podolak, M. and Cameron, A. G. W.: 1974, Icarus 22 , 123.

Pollack, J. B. and Reynolds, R. T.: 1974, Icarus 21 , 248.

Pollard. D. and Ingersoll, A. P.: 1975, to be published.

Prinn, R. G.: 1970, Icarus 13 , 424.

Prinn, R. G. and Lewis, J. S.: 1975, Science 190 , 274.

Reese, E. J. and Smith, B. A.: 1968, Icarus 9 , 474.

Ridgway, S. T.: 1974, Astrophys. J. 187 , L41.

Roberts, P. H.: 1968, Phil. Trans. Roy. Soc. London A263 , 93.

Salpeter, E. E.: 1973, Astrophys. J. 181 , L83.

Savage, B. D. and Danielson, R. E.: 1968, in P. J. Brancazio and A. G. W. Cameron (eds.), Infrared Astronomy , Gordon and Breach, New York, p. 211.

Smith, B. A.: 1975, Paper presented at Jupiter Conference, Tucson, Arizona, May 19–23, 1975.

Smoluchowski, R.: 1973, Astrophys. J. 185 , L95.

Solberg, H. G., Jr.: 1969, Planetary Space Sci. 17 , 1573.

Spiegel, E. N.: 1963, Astrophys. J. 138 , 216.

Stauffer, D. and Kiang, C. S.: 1974, Icarus 21 , 129.

Stone, P. H.: 1967, J. Atmospheric Sci. 24 , 642.

Stone, P. H.: 1971, Geophys. Fluid Dyn. 2 , 147.

Stone, P. H.: 1972, J. Atmospheric Sci. 29 , 405.

Stone, P. H.: 1974, J. Atmospheric Sci. 31 , 1471.

Streett, W. B.: 1973, Astrophys. J. 186 , 1107.

Streett, W. B., Ringermacher, H. I., and Veronis, G.: 1971, Icarus 14 , 319.

Strobel, D. F.: 1973, J. Atmospheric Sci. 30 , 489.

Strobel, D. F.: 1974, Astrophys. J. 192 , L47.

Strobel, D. F. and Smith, G. R.: 1973, J. Atmospheric Sci. 30 , 718, 964 (corrigendum).

Swindell, W. and Doose, L. R.: 1974, J. Geophys. Res. 79 , 3634.

Taylor, D. J.: 1965, Icarus 4 362.

Taylor, F. W.: 1973, J. Atmospheric Sci. 30 , 677.

Terrile, R. J. and Westphal, J. A.: 1975, Amer. Astron. Soc. Div. Planetary Sci., 6th Annual Meeting, Columbia, Md.

Tomasko, M. G.: 1974, Astrophys. J. 187 , 641.

Tomasko, M. G., Clements, A. E., and Castillo, N. D.: 1974, J. Geophys. Res. 79 , 3653.

Trafton, L. M.: 1967, Astrophys. J. 147 , 765.

Trafton, L. M.: 1973, Astrophys. J. 179 , 971.

Trafton, L. M. and Stone, P. H.: 1974, Astrophys. J. 188 , 649.

Vapillion, L., Combes, M., and Lecacheux, J.: 1974, Astron. Astrophys. 29 135.

Veverka, J., Wasserman, L. H., Elliot, J., Sagan, C., and Liller, W.: 1974, Astron. J. 79 , 74.

Wallace, L., Caldwell, J. J., and Savage, B. D.: 1972, Astrophys. J. 172 , 755.

Wallace, L., Prather, M., and Belton, M. J. S.: 1974, Astrophys. J. 193 , 481.

Wasserman, L. H.: 1974, Icarus 22 , 105.

Weidenschilling, S. J. and Lewis, J. S.: 1973, Icarus 20 , 465.

Westphal, J. A., Matthews, K., and Terrile, R. J.: 1974, Astrophys. J. 188 , L111.

Williams, G. P. and Robinson, J. B.: 1973, J. Atmospheric Sci. 30 , 684.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Division of Geological and Planetary Sciences, California Institute of Technology, 91125, Pasadena, Calif., U.S.A

Andrew P. Ingersoll

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Additional information

Contribution No. 2652 of the Division of Geological and Planetary Sciences, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, Calif. 91125, U.S.A.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Ingersoll, A.P. The atmosphere of Jupiter. Space Sci Rev 18 , 603–639 (1976). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00169519

Download citation

Received : 28 July 1975

Issue Date : March 1976

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00169519

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Atmospheric Model

- Thermal Structure

- Current Information

- Neutral Atmosphere

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

NASA’s Juno Mission Uncovers Heart of Jovian Moon’s Volcanic Rage

The north polar region of Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io was captured by NASA’s Juno during the spacecraft’s 57th close pass of the gas giant on Dec. 30, 2023. Data from recent flybys is helping scientists understand Io’s interior.

A new study points to why, and how, Io became the most volcanic body in the solar system.

Scientists with NASA’s Juno mission to Jupiter have discovered that the volcanoes on Jupiter’s moon Io are each likely powered by their own chamber of roiling hot magma rather than an ocean of magma. The finding solves a 44-year-old mystery about the subsurface origins of the moon’s most demonstrative geologic features.

A paper on the source of Io’s volcanism was published on Thursday, Dec. 12, in the journal Nature, and the findings, as well as other Io science results, were discussed during a media briefing in Washington at the American Geophysical Union’s annual meeting, the country’s largest gathering of Earth and space scientists.

About the size of Earth’s Moon, Io is known as the most volcanically active body in our solar system. The moon is home to an estimated 400 volcanoes, which blast lava and plumes in seemingly continuous eruptions that contribute to the coating on its surface.

Although the moon was discovered by Galileo Galilei on Jan. 8, 1610, volcanic activity there wasn’t discovered until 1979, when imaging scientist Linda Morabito of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California first identified a volcanic plume in an image from the agency’s Voyager 1 spacecraft.

This animated tour of Jupiter’s fiery moon Io, based on data collected by NASA’s Juno mission, shows volcanic plumes, a view of lava on the surface, and the moon’s internal structure.

“Since Morabito’s discovery, planetary scientists have wondered how the volcanoes were fed from the lava underneath the surface,” said Scott Bolton, Juno principal investigator from the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. “Was there a shallow ocean of white-hot magma fueling the volcanoes, or was their source more localized? We knew data from Juno’s two very close flybys could give us some insights on how this tortured moon actually worked.”

The Juno spacecraft made extremely close flybys of Io in December 2023 and February 2024 , getting within about 930 miles (1,500 kilometers) of its pizza-faced surface. During the close approaches, Juno communicated with NASA’s Deep Space Network , acquiring high-precision, dual-frequency Doppler data, which was used to measure Io’s gravity by tracking how it affected the spacecraft’s acceleration. What the mission learned about the moon’s gravity from those flybys led to the new paper by revealing more details about the effects of a phenomenon called tidal flexing.

Prince of Jovian Tides

Io is extremely close to mammoth Jupiter, and its elliptical orbit whips it around the gas giant once every 42.5 hours. As the distance varies, so does Jupiter’s gravitational pull, which leads to the moon being relentlessly squeezed. The result: an extreme case of tidal flexing — friction from tidal forces that generates internal heat.

Your browser cannot play the provided video file(s).

This five-frame sequence shows a giant plume erupting from Io’s Tvashtar volcano, extending 200 miles (330 kilometers) above the fiery moon’s surface. It was captured over an eight-minute period by NASA’s New Horizons mission as the spacecraft flew by Jupiter in 2007.

“This constant flexing creates immense energy, which literally melts portions of Io’s interior,” said Bolton. “If Io has a global magma ocean, we knew the signature of its tidal deformation would be much larger than a more rigid, mostly solid interior. Thus, depending on the results from Juno’s probing of Io’s gravity field, we would be able to tell if a global magma ocean was hiding beneath its surface.”

The Juno team compared Doppler data from their two flybys with observations from the agency’s previous missions to the Jovian system and from ground telescopes. They found tidal deformation consistent with Io not having a shallow global magma ocean.

“Juno’s discovery that tidal forces do not always create global magma oceans does more than prompt us to rethink what we know about Io’s interior,” said lead author Ryan Park, a Juno co-investigator and supervisor of the Solar System Dynamics Group at JPL. “It has implications for our understanding of other moons, such as Enceladus and Europa, and even exoplanets and super-Earths. Our new findings provide an opportunity to rethink what we know about planetary formation and evolution.”

There’s more science on the horizon. The spacecraft made its 66th science flyby over Jupiter’s mysterious cloud tops on Nov. 24. Its next close approach to the gas giant will occur 12:22 a.m. EST, Dec. 27. At the time of perijove, when Juno’s orbit is closest to the planet’s center, the spacecraft will be about 2,175 miles (3,500 kilometers) above Jupiter’s cloud tops and will have logged 645.7 million miles (1.039 billion kilometers) since entering the gas giant’s orbit in 2016.

More About Juno

JPL, a division of Caltech in Pasadena, California, manages the Juno mission for the principal investigator, Scott Bolton, of the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. Juno is part of NASA’s New Frontiers Program, which is managed at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, for the agency’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington. The Italian Space Agency (ASI) funded the Jovian InfraRed Auroral Mapper. Lockheed Martin Space in Denver built and operates the spacecraft. Various other institutions around the U.S. provided several of the other scientific instruments on Juno.

More information about Juno is available at:

https://science.nasa.gov/mission/juno

News Media Contact

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

818-393-9011

Karen Fox / Erin Morton

NASA Headquarters, Washington

202-385-1287 / 202-805-9393

[email protected] / [email protected]

Southwest Research Institute, San Antonio

210-522-2254

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 18 December 2024

Tidally driven remelting around 4.35 billion years ago indicates the Moon is old

- Francis Nimmo ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3573-5915 1 ,

- Thorsten Kleine ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4657-5961 2 &

- Alessandro Morbidelli ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8476-7687 3 , 4

Nature volume 636 , pages 598–602 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

19k Accesses

2172 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Early solar system

- Geochemistry

The last giant impact on Earth is thought to have formed the Moon 1 . The timing of this event can be determined by dating the different rocks assumed to have crystallized from the lunar magma ocean (LMO). This has led to a wide range of estimates for the age of the Moon between 4.35 and 4.51 billion years ago (Ga), depending on whether ages for lunar whole-rock samples 2 , 3 , 4 or individual zircon grains 5 , 6 , 7 are used. Here we argue that the frequent occurrence of approximately 4.35-Ga ages among lunar rocks and a spike in zircon ages at about the same time 8 is indicative of a remelting event driven by the Moon’s orbital evolution rather than the original crystallization of the LMO. We show that during passage through the Laplace plane transition 9 , the Moon experienced sufficient tidal heating and melting to reset the formation ages of most lunar samples, while retaining an earlier frozen-in shape 10 and rare, earlier-formed zircons. This paradigm reconciles existing discrepancies in estimates for the crystallization time of the LMO, and permits formation of the Moon within a few tens of million years of Solar System formation, consistent with dynamical models of terrestrial planet formation 11 . Remelting of the Moon also explains the lower number of lunar impact basins than expected 12 , 13 , and allows metal from planetesimals accreted to the Moon after its formation to be removed to the lunar core, explaining the apparent deficit of such materials in the Moon compared with Earth 14 .

Similar content being viewed by others

Moon’s high-energy giant-impact origin and differentiation timeline inferred from Ca and Mg stable isotopes

Giant impacts and the origin and evolution of continents

Onset of the Earth’s hydrological cycle four billion years ago or earlier

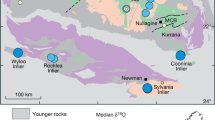

An age for the Moon can be determined by dating a process that results in chemical fractionation of parent and daughter elements of a suitable radionuclide chronometer and that can be closely linked to formation of the Moon itself. One such process is the crystallization of the lunar magma ocean (LMO), which led to density-driven separation of early mafic cumulates that sank to the bottom from buoyant plagioclase-rich cumulates that floated to the top of the LMO, forming the ferroan anorthosites (FANs) that dominate the lunar crust 15 . Crystallization of the LMO produced a residual liquid referred to as KREEP (for strong enrichments in potassium, rare earth elements and phosphorus), the formation of which is frequently used to mark the end of the LMO’s solidification 15 . Ages for the distinct early- and late-formed products of the LMO are remarkably consistent and all give an age of approximately 4.35 billion years ago (Ga), including (1) the most reliable crystallization ages of FANs, (2) the 147 Sm– 143 Nd and 176 Lu– 176 Hf model ages of KREEP, (3) a whole-rock 146 Sm– 142 Nd isochron of FANs, mare basalts (which formed by remelting of the LMO’s mafic cumulates) and KREEP, and (4) crystallization ages of the magnesian suite (Mg suite; which represent melts intruded into the earlier-formed anorthositic crust) (see summary of ages in ref. 16 ). These ages have been interpreted to reflect rapid crystallization of the LMO and late formation of the Moon at approximately 4.35 Ga (refs. 2 , 4 , 16 ). However, thermal evolution models predict a more protracted LMO solidification, and interpreting the aforementioned ages within the framework of such models leads to an estimated earlier Moon formation at 4.425 ± 0.025 Ga (ref. 17 ). Either way, these young proposed ages are problematic for two reasons. First, they are late compared with the predictions of most dynamical models of planet formation 11 , 18 . Second, they are inconsistent with the occurrence of rare lunar zircons with older ages 5 , 7 and hafnium isotopic compositions indicative of derivation from a KREEP source that may have formed as early as about 4.5 Ga (ref. 6 ), implying that the Moon would have formed even earlier. Early Moon formation ages have been proposed based on an approximately 4.51-Ga rubidium–strontium model for volatile loss from the Moon 19 and an approximately 4.52 Ga hafnium–tungsten (Hf–W) model age for lunar core formation 20 , but the veracity of both ages is debated 21 , 22 . Nevertheless, if the Moon did form early, then the clustering of approximately 4.35-Ga lunar ages must record a major magmatic event unrelated to the LMO 16 ; one such possible event is a large impact, for instance, the one that formed the South Pole–Aitken (SPA) Basin 8 .

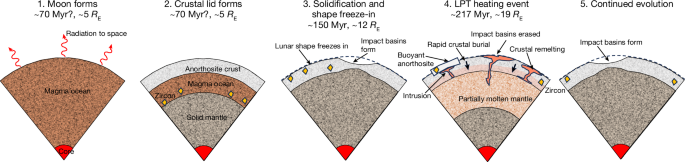

Here we argue that the approximately 4.35-Ga age records an episode of tidal heating, and is not directly tied to either the formation of the Moon or the crystallization of the original post-impact magma ocean. Tidal heating has previously been proposed as an explanation for some of the Moon’s long-wavelength crustal features 23 . The tidally heated Moon was a ‘heat pipe’ body similar to Jupiter’s moon Io, in which heat is advected by hot melt intruding or erupting at the surface, rather than being conducted 24 , 25 . In this picture, partial melt percolates rapidly through the lunar mantle, causing widespread isotopic re-equilibration. The continued eruption of material prevents the development of a true magma ocean 26 and results in rapid burial and/or reheating of the crust. As shown below, these processes should generally result in thermal resetting of the isotopic systems frequently used to date lunar samples, perhaps apart from those in some near-surface zircons. As such, a tidally driven remelting event at about 4.35 Ga resolves existing lunar chronological paradoxes and provides information on how tidal dissipation in the Earth has varied over time. Figure 1 summarizes our predicted timeline of events.

The timing of Moon formation and initial magma ocean freezing is uncertain. Zircons form during the final stages of LMO crystallization and are then transported upwards during eruptions. The Moon probably formed at around 5 R E (ref. 53 ) and its shape froze-in at about 12 R E (see text) and was not modified by the later tidal heating event (the LPT) at about 19 R E . However, the intense volcanism and reheating and/or burial associated with this event reset all crustal chronometers except for relict zircons, and erased pre-existing impact basins. Here time in million years (Myr) is counted forwards from the formation of the Solar System at 4,568 Myr before present.

Remelting during the Laplace plane transition at 4.35 Ga

Three possible episodes of tidal heating of the Moon can be identified: the evection resonance, at approximately 8 Earth radii ( R E ) 27 , 28 , 29 ; the Laplace plane transition (LPT), at 16–22 R E (ref. 9 ) and the associated inner and outer 3:2 resonances 30 ; and the Cassini state transition, at 30–34 R E (ref. 31 ). These resonances occur, respectively: when the Moon’s orbit precession period equals one year; when the effects of the Sun and Earth on the Moon’s orbital precession are equal; and when the lunar spin and orbit precession periods are equal. Of these transitions, the Cassini state transition occurs at the largest semi-major axis and thus the magnitude of tidal heating is low. Typical values are less than 0.1 W m −2 (ref. 32 ), which are unlikely to trigger widespread melting of the Moon. For reasons explained below, the Moon’s passage through the evection resonance is unlikely to be the main driver for remelting, simply because, to occur at 4.35 Ga, it would require the early Earth to be very non-dissipative, even less so than Jupiter, which is implausible. For these reasons, we focus here on the LPT, which was originally proposed to explain the high inclination of the Moon’s orbit 9 .

The peak tidal heating rate during the LPT is estimated to be 10 14 –10 15 W (3–30 W m −2 ) for a few to several tens of million years 9 , 30 , 33 . The primary reason for the large energy release is that a high orbital eccentricity leads to strong tidal heating and a rapid decrease in the lunar semi-major axis. The heat flux range during the LPT may be compared with the present-day tidal heat production rate in Io of about 2.5 W m −2 (ref. 34 ), indicating that the Moon experienced Io-like or larger heat fluxes during the LPT.

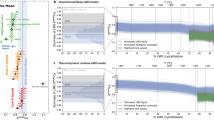

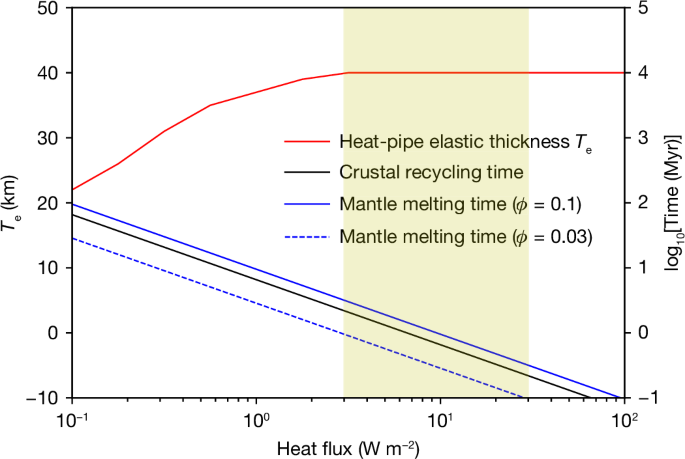

These high heat fluxes imply prodigious mantle melting and volcanism. Assuming that the tidally generated heat is removed from the mantle via advection of melt, we can calculate how long it takes for the entire mantle to be fluxed through the melting region ( Methods ). Figure 2 shows that for the estimated LPT heat fluxes, this timescale is of order a few million years, depending on the melt fraction. Thus, over the duration of the LPT heating event 9 , 30 , we expect the entire mantle to be partially remelted a few times. However, because of the rapid melt removal, we do not expect an actual magma ocean to form 26 .

The shaded box denotes the inferred tidal heat flux during the LPT 9 . A heat-pipe Moon can retain a thick elastic layer while recycling the entire crust and remelting the entire mantle in a time short compared with the few to tens of million years duration of a tidal heating event. The crustal thickness is taken to be 40 km and ϕ is the mean mantle melt fraction. Further details can be found in Methods .

Source Data

Crustal recycling and zircon resetting

Melt produced during the LPT may be either primarily erupted at the surface or intruded within the crust; different regions of the Moon will be dominated by intrusion or extrusion depending on the local density contrast between melt and crust 35 . Pre-existing anorthositic crustal blocks, being low density, are likely to be intrusion dominated.

For end-member cases where all melts are erupted to the surface, crustal material is continually buried and advected downwards by erupting lavas. Sufficiently deep burial will result in thermal resetting and, eventually, remelting. The characteristic timescale to reset the entire crust t o is simply t o = h c / u , where h c is the crustal thickness and u is the areally averaged vertical melt velocity. Figure 2 plots the crustal recycling time as a function of the heat flux and shows that for the LPT range of 3–30 W m −2 , this time is about 0.1–1 Myr ( Methods ). Given the likely LPT duration of a few to tens of million years 9 , 30 , 33 , complete recycling is expected, so that the final crustal ages recorded in these regions will simply be the time at which the LPT-driven recycling ceased.

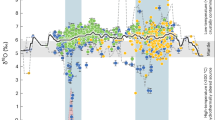

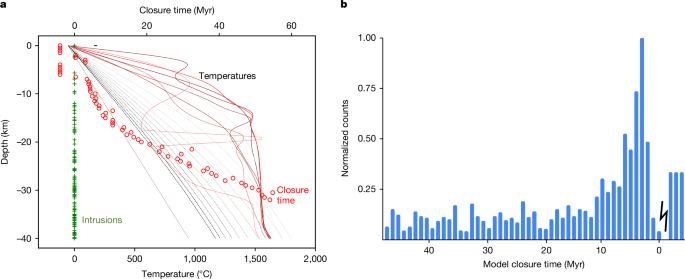

For areas that experience intrusive rather than extrusive volcanism, we created a simple conductive thermal evolution model to study the effects of multiple intrusions, and track how these intrusions reset the ages recorded by rocks and zircons ( Methods ). Figure 3a shows snapshots from an example model. The crust heats up while intrusions (green crosses) are added over a period of 3.5 Myr appropriate for the LPT (red lines), and then subsequently cools (grey and black lines). Zircons (red circles) record a lead–lead (Pb–Pb) closure time (relative to the model start time) depending on their cooling history. Some near-surface zircons (negative ages) are never reset because they cool too fast; deep-seated zircons cool slowly and thus record a wide range of closure times. In between, there is a pile-up of ages around 3–5 Myr (near the time heating ends in this particular model), because this region cools rapidly once the heating episode ends. Figure 3b plots a histogram of model zircon Pb–Pb closure times using 30 realizations, similar to Fig. 3a . We find that there is a peak in the distribution at 3–5 Myr, and a small fraction (about 12%) of zircons are not reset at all. These model results—a narrow peak 8 and a few ancient zircons 5 , 7 —strongly resemble the characteristics of actual lunar zircons.

The tidal heating and intrusions begin at 0 Myr and end at 3.5 Myr. a , A single realization of our thermal model. The solid red lines show temperatures at equally spaced times from 0 Myr to 3.5 Myr; the grey and black dashed lines from 5 Myr to 55 Myr. The green crosses show the depths of individual intrusions, where here the intrusion scale height is 20 km. The red circles denote the Pb–Pb closure time for 50-μm-radius zircons. Negative values indicate zircons that are never reset. Here we assume a melt advection velocity u = 6 cm yr −1 and the intrusion thickness is 2 km ( Methods ). b , Histogram of Pb–Pb closure time from 30 realizations, where the count is normalized to the largest value. Negative closure times mean that the zircons were never reset, so the distribution of ages is arbitrary. It is noted that the pronounced peak is approximately coincident with the end of the tidal heating event.

Apart from the zircons, tidal heating during the LPT resolves other paradoxes in the chronology of the Moon. First, mare basalts, FANs and KREEP-rich samples plot along a single 146 Sm– 142 Nd isochron 4 , 36 , which has been interpreted to indicate that these samples were in isotopic equilibrium at approximately 4.35 Ga. These samples originate from various depths within the Moon, ranging from the first tens of kilometres down to a few hundreds to 1,000 km (refs. 37 , 38 ). Consequently, attaining isotopic equilibrium for such a significant volume of the Moon is only possible by large-scale advection of melt. This, combined with the widespread occurrence of approximately 4.35-Ga ages among lunar samples, has until now been ascribed to a late formation of the Moon and rapid solidification of the LMO 4 , 16 . However, thermal models suggest a longer-lived LMO, which should have produced crystallization products with distinct ages 17 . A tidal heating event explains both the preponderance of approximately 4.35-Ga lunar ages 16 and isotopic equilibrium across large portions of the Moon 4 , given that this event was short-lived (a few tens of million years at most 9 , 30 , 33 ) with respect to the uncertainties of the lunar ages.

Second, the lunar Mg suite appears to derive from distinct reservoirs of the LMO, including mafic cumulates from the early stages of LMO solidification, plagioclase-rich cumulates similar to FANs, and KREEP. Thus, the Mg suite must have formed by remelting after initial LMO crystallization 37 . Crystallization ages of Mg-suite rocks also cluster around approximately 4.35 Ga, which so far has been explained by remelting due to cumulate overturn immediately after rapid LMO solidification 16 . However, tidal remelting of the Moon will result in intrusion of melt into any pre-existing crust, naturally explaining the close temporal link between the Mg-suite rocks and the earlier-formed FANs. Our models show that these intrusions result in resetting of ages for nearby FANs (Extended Data Fig. 1 ), consistent with the indistinguishable ages of FANs and Mg-suite rocks. Moreover, this scenario permits the preservation of older ages for those FANs that remained more distant from any intrusion, although the current evidence for such rocks is weak 39 .

Although in principle the SPA Basin 8 or the older, predicted Procellarum Basin 40 could have caused the resetting event recorded in the approximately 4.35-Ga lunar ages, recent models and analysis documented in Methods do not provide strong support for these ideas. In our model, the SPA Basin should be younger than 4.35 Ga, because otherwise it would have been erased.

Implications for the early evolution of the Moon

A tidally induced remelting of the Moon at approximately 4.35 Ga is consistent with several prominent features of the Moon, including the survival of the Moon’s fossil bulge, the absence of ancient impact basins, and the disparate late accretionary histories of Earth and the Moon. The Moon appears to have ‘frozen in’ its shape at some earlier epoch when it was closer to the Earth and had different orbital or rotational characteristics 10 , 41 . Although the details are controversial, freezing in this fossil bulge requires the development of a rigid elastic layer, which must not be disrupted by a later tidal heating event. Importantly, one of the characteristics of an extrusive heat-pipe body is that the bulk of crust at any time is cool and rigid 24 , thus allowing a fossil bulge to persist.

A previous study 10 found that the fossil bulge can be explained if a 12.8-km-thick elastic layer developed when the Moon was at a distance of 13 R E , whereas an elastic thickness T e of 25 km requires a semi-major axis of 16 R E . Thus, the fossil figure was probably established before the LPT. If T e had decreased below these values subsequently, the fossil bulge would have been reduced. However, Fig. 2 shows that the T e inferred for an extrusive heat-pipe Moon during the LPT (solid red line) can be up to 40 km and thus permit fossil-bulge survival. Intrusions would reduce this value but still permit a cold, rigid layer to persist 25 .

Although the Moon is canonically cratered, with about 50 impact basins, dynamical models suggest that it should host more 12 . One recent study suggested that all basins and craters forming before 4.35–4.41 Ga were erased 13 . Some ancient impacts may have gone unrecorded because they occurred while a subsurface magma ocean was present 42 . But remelting in the mantle and the massive volcanism and resurfacing associated with the approximately 4.35-Ga tidal heating event provides an alternative way of erasing the Moon’s earlier bombardment history and explaining the observed basin and crater population.

Finally, a puzzle concerning the Moon is the much lower concentration of highly siderophile elements (HSEs) in its mantle compared with Earth 14 . Previous explanations for this feature include disproportional late accretion of large objects to Earth 43 and late HSE removal from the lunar mantle during slow magma ocean crystallization terminated by mantle overturn 12 . Our remelting model offers an alternative, as follows. After the original magma ocean crystallized, subsequent impacts will have stranded metal in the lunar mantle 44 . A later remelting of the mantle will have remobilized this metal, which would scavenge HSEs as they descend to the lunar core. If the lunar mantle lost all the HSEs accumulated before 4.35 Ga, the model lunar HSE concentrations delivered by subsequent impacts match those measured, assuming 30% retention of impact material on the Moon 45 . It is striking that this argument, based solely on dynamical simulations, yields an onset time for HSE retention of approximately 4.35 Ga (refs. 12 , 13 , 45 ), consistent with our remelting hypothesis.

Implications for the age of the Moon

Interpretation of the approximately 4.35-Ga lunar ages as a result of tidal heating rather than original LMO crystallization implies that the Moon formed earlier. As the LPT occurs at a particular semi-major axis (16–22 R E ) 9 , by tying it to a remelting event at 4.35 Ga we can make inferences about the Moon’s early orbital evolution. The primary driver of lunar migration is tidal dissipation in Earth, parameterized by the dissipation factor Q E . Early migration was rapid and probably on a timescale comparable to that on which Earth was evolving during its recovery from the Moon-forming impact. Consequently, predicting Q E from first principles is challenging and depends on poorly known factors such as the timescale for Earth’s magma ocean crystallization and the thickness and duration of any early atmosphere 46 , 47 .

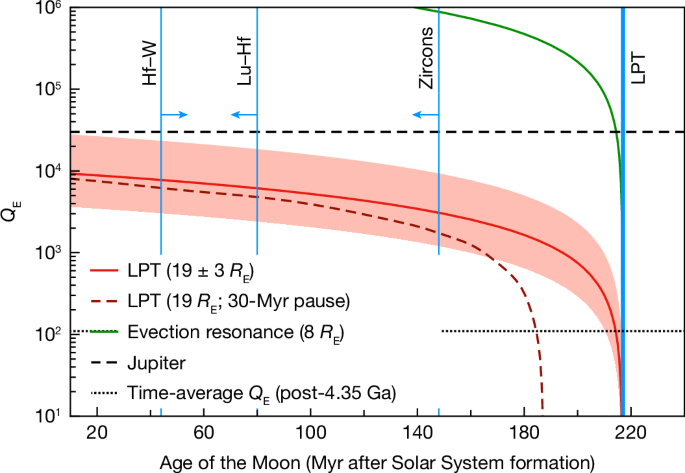

Nonetheless, we can deduce an average Q E applicable to this period of lunar evolution ( Methods ). The red line in Fig. 4 shows the trade-off between the time the Moon formed and the mean Q E required for it to reach 19 R E at 4.35 Ga. The uncertainty in the LPT distance (±3 R E ) is indicated by the red shading. An early formation time allows a less dissipative Earth (higher Q E ). The Moon may have stalled at the LPT for some tens of million years 9 , 30 , 34 , but Fig. 4 shows that this has very little effect on Q E except if the Moon formed late (which is ruled out by the zircon ages; see below). The Q E values derived are generally much higher (less dissipative) than the present-day solid Earth, for which Q E ≈ 300 (ref. 48 ). However, they are lower than the Q of Jupiter, which has been measured to be roughly 3 × 10 4 using astrometry 49 . One would not expect a solid silicate body, even if fully molten, to be less dissipative than a gas giant like Jupiter 50 , and so the Q of Jupiter can be taken as strict upper limit for Q E .

Dissipation factor Q E shown as a function of Moon formation time for the Earth to reach 19 ± 3 R E at 4.35 Ga (red line). The dashed red line includes a pause at the LPT of 30 Myr (see text). The horizontal black lines indicate two constraints on Q E : the mean value after 4.35 Ga (see text); and the measured value of Q for Jupiter 49 , which we take to be an upper bound for Earth. The vertical blue lines denote the time of the LPT, Pb–Pb ages of rare individual zircons 5 , 7 , a Lu–Hf model age for KREEP formation derived from lunar zircons 6 , and the Hf–W model age for core formation on Earth, which provides the earliest possible time of Moon formation 52 .

Figure 4 shows that the time interval between the formation of the Moon and the onset of the LPT is uncertain; it could be as much as about 200 Myr or as short as about 10 Myr. The latter interval is consistent with long-term orbital evolution models 51 , where the Moon reaches 20 R E about 10 Myr after formation. However, also shown in Fig. 4 are the ages of the oldest lunar zircons as well as the Lu–Hf model age of KREEP formation as determined on lunar zircons. As these zircons formed after substantial differentiation of the Moon 6 , the Moon must have formed before these zircons crystallized at approximately 4.43 Ga, that is, at least approximately 80 Myr before the LPT. Conversely, a lower limit for the time of Moon formation is provided by the two-stage Hf–W model of core formation in Earth of 4.533 Ga, which provides the earliest time at which core formation can have ceased 52 . As the last core formation event on Earth is thought to have been triggered by the Moon-forming impact, this model age also provides the earliest time at which the Moon can have formed, which is about 180 Myr before the LPT.

Although the poor knowledge of Q E limits our ability to precisely date the formation of the Moon using the time of the LPT, our model strongly suggests that the Moon formed much earlier than 4.35 Ga, probably in the range of 4.43–4.53 Ga. Dynamical models show that terrestrial planet formation is sufficiently stochastic to allow for a Moon-forming event as late as about 200 Myr, even starting from a concentrated distribution of material around 1 AU (ref. 11 ). However, such a protracted phase of terrestrial planet formation typically leads to systems that are dynamically overexcited, and the amount of material accreted by Earth after formation of the Moon is too small to account for the abundances of HSEs in Earth’s mantle 11 , 18 . Formation of the Moon at approximately 4.5 Ga would solve these problems, but in this case the Moon would have accumulated many more impact basins and more late-accreted material than observed 12 , 13 . Thus, our proposal of an early Moon formation followed by a late, tidally driven remelting appears a likely way of reconciling these apparently contradictory observations.

Heat-pipe Moon

The advection–diffusion equation in a two-dimensional Cartesian geometry with no internal heating is written 24

where T is temperature, κ is the thermal diffusivity, u is the downwards velocity of the crust due to burial and z is positive downwards. In steady state, the solution is

where T s is the surface temperature and T b is the temperature at the base of the crust (thickness h c ). It is noted that this expression reduces to the standard conduction equation in the limit that u is small. The conductive heat flux at the base of the crust is F = ( T b − T s ) u / κ , which can be rewritten as ρC p u ( T b − T s ), the advective heat flux (the two must balance in steady state). Here ρ is the density and C p is the specific heat capacity, modified to include a latent heat effect (that is, we augment the usual specific heat capacity with a term L /( T b − T s ) where L is the latent heat).

The isotherm defining the base of the elastic layer in oceanic mantle material on Earth is at about 720 K (ref. 54 ). We use this isotherm and equation ( 1 ) to determine the elastic thickness as a function of the heat flux. For a specified heat flux F , we can also solve for u and thus derive the overturn time t c / u . Thus, if F = 10 W m −2 , we obtain u = 0.06 m yr −1 and a crustal overturn time of 0.67 Myr.

The mantle melting timescale may be derived as follows. The surface flow rate of material is 4π \({R}_{M}^{2}\) u , and if the melt fraction is ϕ then the rate at which mantle material is fluxed through the melting zone is 4π \({R}_{M}^{2}\) u / ϕ , where R M is the lunar radius (1,740 km). The total volume of the mantle is approximately that of the whole Moon, 4/3π \({R}_{M}^{3}\) . Thus, the timescale to flux the whole mantle through the melting zone is R M ϕ /3 u . If ϕ = 0.1 and u = 0.1 m yr −1 , then the timescale is 0.58 Myr, comparable to the crustal overturn timescale.

The parameters adopted are as follows: ρ = 2,600 kg m −3 , k = 2 W m −1 K −1 (ref. 17 ), L = 450 kJ kg −1 , C p = 1,200 J kg −1 K −1 , T s = 220 K and T b = 1,500 K. In our baseline models, we take h c = 40 km (ref. 55 ). It has been suggested previously that the early Moon was a heat-pipe body 56 , but not in the context of a tidal heating event.

Intrusive resetting

We solve a simple static one-dimensional finite-difference heat-conduction equation in which intrusions are added at intervals. To take into account the random nature of intrusive behaviour, we assign a probability distribution for the height above the base of the crust z ′ at which the intrusion occurs, where the probability is proportional to exp(− z ′/ δ ), with δ an user-specified scale height. A low value of δ means that intrusions are concentrated towards the base of the crust. For simplicity, we assume a single characteristic intrusion thickness Δ d (an integer multiple of the grid spacing Δ z ) and a characteristic time interval between intrusions Δ t . Once Δ d is specified, Δ t is then determined by the requirement that Δ d /Δ t = u , where u is calculated as described above.

At intervals Δ t , we intrude an intrusion of thickness Δ d at a randomly chosen grid point in the crust. The intruded material is given an initial temperature of T m and the surface temperature T s is kept constant. The basal heat flux F b is also kept constant at a value appropriate for the Moon before the heating event; the assumption is that tidal heat produced in the mantle is being transported by advection (melt ascent) rather than conduction. As intrusions proceed, the basal temperature will increase. Tidal heating starts at model time zero, ends after 3.5 Myr and we then continue the model up to 55 Myr. The finite-difference timestep is set to be 0.3Δ z 2 / κ to satisfy the Courant criterion, with Δ z = 0.5 km. The thermal parameters are the same as for the heat-pipe model (above); other nominal parameter values are: T m = 1,550 °C, F b = 50 mW m −2 and Δ d = 2 km.

We use the same model to investigate the extent to which heating by the intrusions results in resetting of Pb–Pb zircon ages. Here we implement a simple model for diffusion to track the time at which diffusive loss effectively ceases; this time will give the age recorded.

For a zircon with constant diffusivity D , the time τ it takes for diffusive loss to penetrate a distance p into the crystal is given by p = (π 2 Dτ ) 1/2 , where π 2 is a factor appropriate for our (assumed spherical) crystal 57 . In reality, D is temperature dependent. We therefore differentiate the constant- D relationship to obtain

Here Δ p is the change in penetration distance over a time interval Δ t . As long as D is changing slowly, we can use this expression to determine how p ( t ) increases with time. Once p ( t ) equals half the radius of the crystal, 7/8 of the crystal volume will have experienced Pb loss, resetting is assumed to have occurred and in the next timestep we restart the calculation setting p = 0 and t = Δ t (to avoid a singularity at the origin). In this manner, we can track when Pb loss effectively ceases. We assume that the diffusivity is given by D 0 exp(− Q / RT ), where for Pb D 0 = 0.11 m 2 s −1 and Q = 550 kJ mol −1 (ref. 58 ) and R is the gas constant. Application of this approach with a cooling rate of 10 °C Myr −1 yields closure temperatures of 968 °C and 877 °C with zircon radii of 100 μm and 10 μm, respectively. These values compare favourably to the values of about 990 °C and 895 °C shown in Fig. 13 of ref. 58 . In our nominal model, we assume a zircon radius of 50 μm.

For a given depth within the Moon, we know how the temperature is evolving with time and can therefore calculate D ( t ) and the time at which the last resetting takes place for any zircons present at that depth. This approach is the basis of the zircon ages shown in Fig. 3 , where a uniform initial distribution of zircons with depth is assumed. The results change minimally (<1%) if we double or halve the zircon radius. If the intrusions are more concentrated towards the base of the crust, the fraction of zircons not undergoing resetting increases, as expected (Extended Data Fig. 2 ). The same analysis for Hf (which diffuses more slowly) shows that around 30% of zircons are not reset for our nominal model parameters. Longer-duration heating events result in more rock resetting (Extended Data Fig. 3 ).

Lunar orbital evolution

Dissipation in the Earth drives outwards evolution of the Moon, whereas dissipation in the Moon circularizes the Moon’s orbit and can also drive inwards orbital evolution 59 . Below we assume that dissipation in the Earth dominates. The semi-major axis evolution of the Moon a is then given by 60 :

Here k 2E and Q E are the tidal Love number and dissipation factor of the Earth, m and M are the mass of the Moon and Earth, respectively, R E is the radius of the Earth and n is the mean motion of the lunar orbit. We take M = 6 × 10 24 kg, m = 7.4 × 10 22 kg, R E = 6,400 km and k 2E = 0.97. The latter value is that appropriate for a strengthless (for example, molten) Earth, rather than taking the present-day value of 0.299, which is due to the rigidity of the present-day mantle 59 . A limitation of all existing models of the LPT 9 , 30 , 34 is that they assume constant Q and k 2 values; we anticipate that incorporating thermal–orbital feedbacks will shorten the period of tidal heating.

The role of ancient impacts

We consider whether it is possible that a large impact that formed the SPA Basin or the older, predicted Procellarum Basin 40 caused the resetting event recorded in the approximately 4.35-Ga lunar ages. Regarding the SPA Basin, there are three possibilities. The first is that ejecta from the SPA impact itself polluted the Apollo region, but models show that this does not take place 61 . Second, SPA melt-sheet material may have been redistributed by subsequent impacts 8 , but we find that the fraction of such material at the Apollo sites was only around 2% (see below). Third, the SPA Basin might have triggered mantle convection and melting 62 , but a potential problem with this model is that the volcanism it produces is long-lived and would not obviously generate the spike in ages that a short period of tidal heating does, and that is observed among the lunar ages. This model also implies melting focused on one hemisphere, whereas ours argues for global melting. Of note, the lunar meteorite Kalahari 009 shows a Pb–Pb age of 4.369 ± 0.007 Ga and based on chemical grounds is thought to derive from the lunar farside, consistent with our model of a global remelting event at around 4.35 Ga (ref. 63 ). As this event will probably have erased any pre-existing basins, we predict that the SPA Basin itself is younger than 4.35 Ga.

Finally, models of the impact that formed the putative Procellarum Basin 45 show that the resulting impact melt is localized and would not be sufficient to cause the kind of global mixing and resetting that the lunar samples appear to require. Thus, current models do not support the idea of impacts being responsible for the resetting event.

Redistribution of material from the SPA Basin

The Apollo sites will have received material originating from the SPA melt sheet and redistributed by subsequent impacts 8 . They will also have received material ejected from other regions of the Moon. We wish to compare the relative masses of these two contributions. The key factor is that the fraction of ejecta travelling with a particular velocity decreases as that velocity increases 64 ; thus more distant impacts supply a lower fraction of ejecta material compared with nearer impacts.

Using the simple Maxwell model 65 , 66 , we can show that the volume of material V s ejected at a radial velocity exceeding a specified value u s ratioed to the total volume of material V ejected is given by

where g is the surface gravity, R t is the transient crater diameter and Z is a constant. A larger transient crater produces a greater fraction of high-velocity material, but the sensitivity is weak 64 . The minimum radial velocity u s required for a particle to travel a distance s is given by ( gs /2) 1/2 .

We need to deduce the transient crater radius R t from the observed crater radius R f . To do so, we use the scaling used in ref. 67 where

Here R c is the simple-complex crater transition radius (9 km for the Moon) and ξ is a constant.

We use a catalogue of all impact craters exceeding 1–2 km diameter on the Moon 68 , a total of 1,296,795 excluding the SPA Basin itself. To calculate the volume of material ejected from a particular region by subsequent impacts, we use the following algorithm for each impact crater. (1) Determine whether the centre of the impact crater falls within the specified region (for example, the SPA melt sheet). (2) If it does, determine the great-circle distance s from the centre of the impact crater to the target location. (3) Calculate the minimum horizontal speed u s required to achieve this distance. (4) Calculate the transient crater radius R t associated with the measured final radius of the crater R f using equation ( 4 ). (5) Use u s , R t and equation ( 3 ) to calculate the volume of material ejected at a speed exceeding u s compared with the total volume of material ejected.

This algorithm can be repeated for each crater observed to determine the total mass ejected from the specified region capable of reaching the target site. We perform this algorithm twice, once for craters within the SPA melt sheet and once for craters elsewhere. The ratio of the two answers gives a measure of what fraction of all material accumulating at the target site is derived from the SPA melt sheet. For our nominal parameter values, we find a value of 1.7%.

We follow ref. 66 and take Z = 2.71. Equation ( 3 ) then yields an exponent of 0.55, slightly lower than the range of 0.6–0.85 advocated by ref. 64 . A higher value yields a lower value of Z and results in a smaller contribution from the SPA basin. For instance, if we take Z = 2.2, then the volume fraction is reduced to 1.4% compared with 1.7% for the nominal model. We use ξ = 0.22 to reproduce the relationship between the transient and final crater diameter derived by ref. 69 . Using a lower value of ξ = 0.13 causes a slight reduction in the volume fraction deriving from the SPA Basin (1.3% compared with 1.7%). We take g = 1.6 m s −2 and use the location (0°, 0°) as an appropriate average of the Apollo site locations. Variations in longitude or latitude by ±10° change the volume fraction answer by less than 0.1%.

Data availability

The output used to produce the figures is available at https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.kprr4xhdz . Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The codes used to generate results are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13968139 .

Canup, R. M. & Asphaug, E. Origin of the Moon in a giant impact near the end of the Earth’s formation. Nature 412 , 708–712 (2001).

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Borg, L. E., Connelly, J. N., Boyet, M. & Carlson, R. W. Chronological evidence that the Moon is either young or did not have a global magma ocean. Nature 477 , 70–72 (2011).

Gaffney, A. M. & Borg, L. E. A young solidification age for the lunar magma ocean. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 140 , 227–240 (2014).

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar

Borg, L. E. et al. Isotopic evidence for a young lunar magma ocean. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 523 , 115706 (2019).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Nemchin, A. et al. Timing of crystallization of the lunar magma ocean constrained by the oldest zircon. Nat. Geosci. 2 , 133–136 (2009).

Barboni, M. et al. Early formation of the Moon 4.51 billion years ago. Sci. Adv. 3 , e1602365 (2017).

Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Greer, J. et al. 4.46 Ga zircons anchor chronology of lunar magma ocean. Geochem. Persp. Let. 27 , 49–53 (2023).

Article Google Scholar

Barboni, M. et al. High-precision U–Pb zircon dating identifies a major magmatic event on the Moon at 4.338 Ga. Sci. Adv. 10 , eadn9871 (2024).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Cuk, M., Hamilton, D. P., Lock, S. J. & Stewart, S. T. Tidal evolution of the Moon from a high-obliquity, high-angular-momentum Earth. Nature 539 , 402–406 (2016).

Matsuyama, I., Trinh, A. & Keane, J. T. The lunar fossil figure in a Cassini state. Planet. Sci. J. 2 , 232 (2021).

Woo, J. M. Y., Nesvorný, D., Scora, J. & Morbidelli, A. Terrestrial planet formation from a ring: long-term simulations accounting for the giant planet instability. Icarus 417 , 116109 (2024).

Morbidelli, A. et al. The timeline of the lunar bombardment: revisited. Icarus 305 , 262–276 (2018).

Nesvorný, D. et al. Early bombardment of the moon: connecting the lunar crater record to the terrestrial planet formation. Icarus 399 , 115545 (2023).

Day, J. M. D. & Walker, R. J. Highly siderophile element depletion in the Moon. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 423 , 114–124 (2015).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Warren, P. H. The magma ocean concept and lunar evolution. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 13 , 201–240 (1985).

Borg, L. E. & Carlson, R. W. The evolving chronology of Moon formation. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 51 , 25–52 (2023).

Maurice, M., Tosi, N., Schwinger, S., Breuer, D. & Kleine, T. A long-lived magma ocean on a young Moon. Sci. Adv. 6 , eaba8949 (2020).

Jacobson, S. A. et al. Highly siderophile elements in Earth’s mantle as a clock for the Moon-forming impact. Nature 508 , 84–87 (2014).

Mezger, K., Maltese, A. & Vollstaedt, H. Accretion and differentiation of early planetary bodies as recorded in the composition of the silicate Earth. Icarus 365 , 114497 (2021).

Thiemens, M. M., Sprung, P., Fonseca, R. O. C., Leitzke, F. P. & Münker, C. Early Moon formation inferred from hafnium–tungsten systematics. Nat. Geosci. 12 , 696–700 (2019).

Borg, L. E., Brennecka, G. A. & Kruijer, T. S. The origin of volatile elements in the Earth–Moon system. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119 , e2115726119 (2022).

Kruijer, T. S., Archer, G. J. & Kleine, T. No 182 W evidence for early Moon formation. Nat. Geosci . https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-021-00820-2 (2021).

Garrick-Bethell, I., Perera, V., Nimmo, F. & Zuber, M. T. The tidal-rotational shape of the Moon and evidence for polar wander. Nature 512 , 181–184 (2014).

O’Reilly, T. C. & Davies, G. F. Magma transport of heat on Io: a mechanism allowing a thick lithosphere. Geophys. Res. Lett. 8 , 313–316 (1981).

Article ADS Google Scholar

Spencer, D. C., Katz, R. F. & Hewitt, I. J. Tidal controls on the lithospheric thickness and topography of Io from magmatic segregation and volcanism modelling. Icarus 359 , 114352 (2021).

Miyazaki, Y. & Stevenson, D. J. A subsurface magma ocean on Io: exploring the steady state of partially molten planetary bodies. Planet. Sci. J. 3 , 256 (2022).

Cuk, M. & Stewart, S. T. Making the Moon from a fast-spinning Earth: a giant impact followed by resonant despinning. Science 338 , 1047–1052 (2012).

Tian, Z., Wisdom, J. & Elkins-Tanton, L. Coupled orbital-thermal evolution of the early Earth–Moon system with a fast-spinning Earth. Icarus 281 , 90–102 (2017).

Rufu, R. & Canup, R. M. Tidal evolution of the evection resonance/quasi-resonance and the angular momentum of the Earth–Moon system. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 125 , e2019JE006312 (2020).

Ćuk, M., Lock, S. J., Stewart, S. T. & Hamilton, D. P. Tidal evolution of the Earth–Moon system with a high initial obliquity. Planet. Sci. J. 2 , 147 (2021).

Siegler, M. A., Bills, B. G. & Paige, D. A. Effects of orbital evolution on lunar ice stability. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 116 , E03010 (2011).

Downey, B. G., Nimmo, F. & Matsuyama, I. The thermal–orbital evolution of the Earth–Moon system with a subsurface magma ocean and fossil figure. Icarus 389 , 115257 (2023).

Tian, Z. & Wisdom, J. Vertical angular momentum constraint on lunar formation and orbital history. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117 , 15460–15464 (2020).

Article ADS MathSciNet CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Veeder, G. J., Matson, D. L., Johnson, T. V., Blaney, D. L. & Goguen, J. D. Io’s heat flow from infrared radiometry: 1983–1993. J. Geophys. Res. 99 , 17095–17162 (1994).

Wilson, L. & Head, J. W. Generation, ascent and eruption of magma on the Moon: new insights into source depths, magma supply, intrusions and effusive/explosive eruptions (part 1: theory). Icarus 283 , 146–175 (2017).

Brandon, A. D. et al. Re-evaluating Nd-142/Nd-144 in lunar mare basalts with implications for the early evolution and bulk Sm/Nd of the Moon. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 73 , 6421–6445 (2009).

Shearer, C. K. et al. Thermal and magmatic evolution of the Moon. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 60 , 365–518 (2006).

Longhi, J. Experimental petrology and petrogenesis of mare volcanics. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 56 , 2235–2251 (1992).

Borg, L. E., Gaffney, A. M. & Shearer, C. K. A review of lunar chronology revealing a preponderance of 4.34–4.37 Ga ages. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 50 , 715–732 (2015).

Whitaker, E. A. The lunar Procellarum Basin. In Multi-ring Basins: Formation and Evolution; Proc. Lunar and Planetary Science Conference 105–111 (Pergamon Press, 1981).

Garrick-Bethell, I., Wisdom, J. & Zuber, M. T. Evidence for a past high-eccentricity lunar orbit. Science 313 , 652–655 (2006).

Article ADS MathSciNet CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Miljković, K. et al. Large impact cratering during lunar magma ocean solidification. Nat. Commun. 12 , 5433 (2021).

Bottke, W. F., Walker, R. J., Day, J. M. D., Nesvorny, D. & Elkins-Tanton, L. Stochastic late accretion to Earth, the Moon, and Mars. Science 330 , 1527–1530 (2010).

Marchi, S., Canup, R. M. & Walker, R. J. Heterogeneous delivery of silicate and metal to the Earth by large planetesimals. Nat. Geosci. 11 , 77–81 (2018).

Zhu, M.-H. et al. Reconstructing the late accretion history of the Moon. Nature 571 , 226–229 (2019).

Zahnle, K. J., Lupu, R., Dobrovolskis, A. & Sleep, N. H. The tethered Moon. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 427 , 74–82 (2015).

Korenaga, J. Rapid solidification of Earth’s magma ocean limits early lunar recession. Icarus 400 , 115564 (2023).

Ray, R. D., Eanes, R. J. & Chao, B. F. Detection of tidal dissipation in the solid Earth by satellite tracking and altimetry. Nature 381 , 595–597 (1996).

Lainey, V., Arlot, J.-E., Karatekin, Ö. & van Hoolst, T. Strong tidal dissipation in Io and Jupiter from astrometric observations. Nature 459 , 957–959 (2009).

Goldreich, P. & Soter, S. Q in the Solar System. Icarus 5 , 375–389 (1966).

Farhat, M., Auclair-Desrotour, P., Boué, G. & Laskar, J. The resonant tidal evolution of the Earth–Moon distance. Astron. Astrophys. 665 , L1 (2022).

Kleine, T. & Walker, R. J. Tungsten isotopes in planets. Ann. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 45 , 389–417 (2017).

Salmon, J. & Canup, R. M. Lunar accretion from a Roche-interior fluid disk. Astrophys. J. 760 , 83 (2012).

Watts, A. B. Isostasy and Flexure of the Lithosphere (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2001).

Wieczorek, M. A. et al. The crust of the Moon as seen by GRAIL. Science 339 , 671–675 (2013).

Moore, W. B., Simon, J. I. & Webb, A. A. G. Heat-pipe planets. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 474 , 13–19 (2017).

Carslaw, H. S. & Jaeger, J. C. Conduction of Heat in Solids (Oxford Univ. Press, 1986).

Cherniak, D. J. & Watson, E. B. Pb diffusion in zircon. Chem. Geol. 172 , 5–24 (2001).

Meyer, J., Elkins-Tanton, L. & Wisdom, J. Coupled thermal–orbital evolution of the early Moon. Icarus 208 , 1–10 (2010).

Murray, C. D. & Dermott, S. F. Solar System Dynamics (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2000); https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139174817 .

Citron, R. I., Smith, D. E., Stewart, S. T., Hood, L. L. & Zuber, M. T. The South Pole–Aitken Basin: constraints on impact excavation, melt, and ejecta. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51 , e2024GL110034 (2024).

Jones, M. J. et al. A South Pole–Aitken impact origin of the lunar compositional asymmetry. Sci. Adv. 8 , eabm8475 (2022).

Snape, J. F. et al. Ancient volcanism on the Moon: insights from Pb isotopes in the MIL 13317 and Kalahari 009 lunar meteorites. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 502 , 84–95 (2018).

Melosh, H. J. Impact Cratering: A Geologic Process (Oxford Univ. Press, 1989).

Croft, S. K. Cratering flow fields: implications for the excavation and transient expansion stages of crater formation. Lunar Planet. Sci. Conf. Proc. 3 , 2347–2378 (1980).

ADS Google Scholar

Barnhart, C. J. & Nimmo, F. Role of impact excavation in distributing clays over Noachian surfaces. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 116 , E01009 (2011).

Zahnle, K., Schenk, P., Levison, H. & Dones, L. Cratering rates in the outer Solar System. Icarus 163 , 263–289 (2003).

Robbins, S. J. A new global database of lunar impact craters >1–2 km: 1. Crater locations and sizes, comparisons with published databases, and global analysis. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 124 , 871–892 (2019).

Potter, R. W. K., Collins, G. S., Kiefer, W. S., McGovern, P. J. & Kring, D. A. Constraining the size of the South Pole–Aitken Basin impact. Icarus 220 , 730–743 (2012).

Ganguly, J. & Tirone, M. Relationship between cooling rate and cooling age of a mineral: theory and applications to meteorites. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 36 , 167–175 (2001).

Download references

Acknowledgements

T.K. and A.M. acknowledge support from the European Research Council Advanced Grant HolyEarth (grant number 101019380).

Open access funding provided by Max Planck Society.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of California Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA, USA

Francis Nimmo

Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research, Göttingen, Germany

Thorsten Kleine

Collège de France, CNRS, PSL University, Sorbonne University, Paris, France

Alessandro Morbidelli

Laboratoire Lagrange, Université Cote d’Azur, CNRS, Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur, Boulevard de l’Observatoire, Nice, France

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

The authors conceived of this study together. F.N. led the paper, carried out all the modelling and wrote the first draft. T.K. contributed the sections on lunar geochronology. A.M. contributed the sections on dynamical constraints on Moon formation and the cratering record. All authors commented on and edited the paper.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Francis Nimmo .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information.

Nature thanks Melanie Barboni and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended data fig. 1 result of intrusion model on sm-nd ages..

a) A realization of the same thermal model as in Fig. 3 but with δ = 4 km (intrusions concentrated towards the base of the crust). The red line shows the maximum temperature experienced at each depth. The green boxes show where intrusions are added. The mid-crust has regions that are reset (maximum temperature exceeds Sm-Nd blocking temperature) but are not actually intruded. The blocking temperature of the Sm-Nd system in plagioclase is from ref. 70 . b) Fraction of crust reset but not intruded as a function of scale height δ and basal heat flux F b .

Extended Data Fig. 2 Sensitivity of zircon results to parameter variations.

a) Fraction of zircons with Pb-Pb ages 3-6 Myr (i.e. as the heating episode ends) (red line) and fraction with Pb-Pb ages that are not reset (black line) as a function of the intrusion scale height δ, based on 30 realizations with F b = 50 mWm −2 and Δd = 2 km. The peak in ages between 3-6 Myr becomes more pronounced as intrusions become more widely distributed throughout the crust (larger δ). b) As for a) but exploring the zircon fraction as a function of basal heat flux F b and intrusion thickness Δd . Here δ = 20 km. Calculation techniques are described in Methods .

Extended Data Fig. 3 Sensitivity of thermally reset crust to duration of heating event.

Sensitivity of fraction of crust reset (in terms of Sm-Nd ages) and not intruded, as a function of the duration of the heating event. The parameter δ is the scale height of the intrusions (small δ means intrusions are more clustered towards the base of the crust).

Source data

Source data fig. 2, source data fig. 3, source data fig. 4, source data extended data fig. 1, source data extended data fig. 2, source data extended data fig. 3, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Nimmo, F., Kleine, T. & Morbidelli, A. Tidally driven remelting around 4.35 billion years ago indicates the Moon is old. Nature 636 , 598–602 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-08231-0

Download citation

Received : 17 April 2024

Accepted : 16 October 2024

Published : 18 December 2024

Issue Date : 19 December 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-08231-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

May 26, 2017 · The initial measurement of Jupiter’s gravity will inform interior models with implications for the extent, existence, and mass of Jupiter’s core. The magnitude of the observed magnetic field observed was 7.766 G, almost twice as strong as expected. More results from Juno’s initial passes are discussed in a companion paper .

Jan 1, 2013 · The paper highlights important achievements in Jupiter study during the last few decades starting from early seventies. During the first two decades of its journey both 'Pioneer' and 'Voyager ...

Feb 21, 2022 · The Juno mission has revolutionized and challenged our understanding of Jupiter. As Juno transitioned to its extended mission, we review the major findings of Jupiter's internal structure relevant to understanding Jupiter's formation and evolution. Results from Juno's investigation of Jupiter's interior structure imply that the planet has compositional gradients and is accordingly non ...

In this research paper, we have explored effects of Jupiter (Guru) mahadasha on Lord Sri Rama according to the planetary positions in his birth chart [1-16] and ascertained its validity by ...

Current information on the neutral atmosphere of Jupiter is reviewed, with approximately equal emphasis on composition and thermal structure on the one hand, and markings and dynamics on the other. Studies based on Pioneer 10 and 11 data are used to refine the atmospheric model. Data on the interior are reviewed for the information they provide on the deep atmosphere. The markings and dynamics ...

Mar 7, 2018 · Read the paper: Jupiter’s atmospheric jet streams extend thousands of kilometres deep. ... Human Technopole (HT) is an interdisciplinary research institute in Milan (Italy) created and supported ...

Jan 30, 2023 · The Chinese scientific community is currently vigorously engaged in exploring the next frontier of Jovian system science and identifying the specific goals for the Chinese Jupiter mission through a series of workshops. This thematic collection will include papers presented at the Chinese Planetary Workshops for Jupiter Sciences.

Oct 5, 2001 · The total mass of Jupiter's satellites is about the same as that of Mars and probably about 1% of the heavy-element mass (everything except hydrogen and helium) inside Jupiter. This is a similar ratio to the heavy-element distribution in our solar system, where the Sun contains around 10 Jupiter masses and the planetary system tens of Earth ...

Dec 12, 2024 · What the mission learned about the moon’s gravity from those flybys led to the new paper by revealing more details about the effects of a phenomenon called tidal flexing. Prince of Jovian Tides. Io is extremely close to mammoth Jupiter, and its elliptical orbit whips it around the gas giant once every 42.5 hours.

5 days ago · The tidally heated Moon was a ‘heat pipe’ body similar to Jupiter’s ... Source data are provided with this paper. ... T.K. and A.M. acknowledge support from the European Research Council ...