An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

How to undertake research as a dental undergraduate

Emma elliott, sathyam sharma.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author.

Issue date 2021.

This article is made available via the PMC Open Access Subset for unrestricted research re-use and secondary analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source. These permissions are granted for the duration of the World Health Organization (WHO) declaration of COVID-19 as a global pandemic.

By Alya Omar , Emma Elliott and Sathyam Sharma

©PeopleImages/E+/Getty Images Plus

How do dentistry and mental health link together? What role do dentists have in addressing patient mental health? How confident do you feel about taking on that role? When you find a research question that interests you and grabs your attention, you shouldn't be afraid to approach a project alongside your studies. For a small group of us at Barts and the London Dental School, this question was related to confidence and education around patient mental health. What started as a small idea ultimately snowballed into a multi-centre research project called 'Open Up', spanning five dental schools across the UK and Ireland. Whether you have high ambitions in research, want to contribute to the field or simply want to explore an area of interest, we hope this serves as a guide to get you started.

When you first consider a research question, you should begin by looking at the literature that already exists in the field - formally known as a 'literature review'. Our research question was 'How confident are UK dental students at addressing patient mental health?'. So we took a step back and looked at the UK clinical picture and the current best available research. You should initially outline the picture within the population you are interested in and follow by evidencing the need for your research question. For example, our literature review covered the following points:

Psychiatric disorders are on the rise within the UK population with 20% of men and 30% of women professionally diagnosed with a psychiatric condition 1

Several studies had already investigated practitioner confidence when addressing patient mental health and reported low confidence 2

We found no studies that assessed UK dental undergraduate education or student confidence around patient mental health.

According to the GDC dental practitioners are in a position where we need to be able to 'identify, explain and manage the impact of medical and psychological conditions'. 3

Once you have a good grasp of the existing literature around your research question you should consider the benefit your work could bring to the dental research community. This will help you plan the project and figure out the best way to answer your research question. We wanted to see if modern dental undergraduate education was creating confident dental students who could comfortably address patient mental health. To be of benefit, we needed to survey the existing clinical year groups in the BDS curriculum and run focus groups to gather dental students' opinions on how their confidence could be enhanced. A literature review and a basic outline of the study puts you in good stead to then approach a potential supervisor.

A supervising tutor will guide your research project with their experience and will ensure you get the most out of it, advising you on how to proceed and helping you collaborate with others. This chosen person can be any tutor who is willing, but someone is much more likely to supervise you if you come to them with at least a partially-formed idea. A supervising tutor is key to helping you secure approval to run your project, assisting you in analysing your findings and guiding your project write-up if you wish to submit it to a journal.

After securing our supervising tutor and successfully pitching the project, we ran our initial study. We found that students believed an interactive workshop with case-based discussion was the best way to improve their confidence when addressing patient mental health. Dr Catherine Marshall, a clinical lecturer in psychiatry, helped us develop such an educational intervention; she also helped us develop pre- and post-workshop surveys that allowed us to see how participant confidence changed as a result of the workshop. She was instrumental in the project, giving expert input on her field. If your topic of interest requires specialist advice, do not be afraid to reach out and collaborate for the best results.

Once you have your research question, methodology and a supervising tutor, you should feel more comfortable with conducting a project alongside your degree. This is a strong starting point, but projects will inevitably change and mould around your circumstances. We initially published work based on research in a single institute, only later realising that we could think bigger and conduct the study across multiple dental schools. Don't restrict yourself, but don't bite off more than you can chew either!

When you first consider a research question, you should begin by looking at the literature that already exists in the field

You need to think ' will my project benefit from participation from a wider group of people ?' Larger groups of study participants can lead to more generalisable data, which is of greater use to researchers. Therefore, we decided to survey the confidence of dental students across multiple dental schools and then deliver our workshop intervention at each school. Student representatives were appointed at each school and were responsible for the research there. This is also a key point - when undertaking research, you should appropriately credit those involved, will they be authors or acknowledgements? It is important to consider this early on and be clear to the people you ask to help with the study.

Our representatives became authors of the study, alongside Dr Marshall and our supervisor, Dr Hurst. Expanding a project can be difficult, but if you want to work on a larger study then you can consider collaborating with students via DentSoc, (or DentSoc presidents), BDSA, conferences or even via shout-outs in the Student BDJ. Using these methods, we were able to collaborate with students at Trinity College Dublin, Newcastle, Kings College London and Dundee.

When conducting research, your circumstances will change and you will have to adapt. For us, we had to work around the COVID-19 pandemic; we had a large multi-centre project that relied on the delivery of an in-person workshop during a massive public health crisis! Admittedly, this isn't something we could have prepared for, but it highlights that research isn't always smooth sailing. We initially planned to collaborate with nine dental schools, but the pandemic meant we had to reconsider, shrink and shorten the project.

Putting your research on hold isn't ever ideal, but sometimes it is best to take a step back and reconsider how the project may need adapting to a change. The change might be something small or large - perhaps you had a personal change in circumstances and what you had planned is no longer feasible. This is fine! Just adapt the work so that what you have done doesn't go to waste.

In our case we had to adapt the research for online delivery of the workshop and restrict the study to the schools that had already made progress with surveying the student body. This change took a long time to consider, leaving the project on a long hiatus. However, once we had taken time to consider these decisions, the changes were easier to implement. Adapting to COVID-19 for us meant brainstorming with our representatives to ensure everyone knew how we were re-designing our methodology.

Sometimes, these changes can be ultimately beneficial! Despite our initial difficulties in organising online virtual webinars in place of our in-person workshops, we found that the format made things easier. It allowed the representatives to be better supported as we could drop in on the virtual sessions if they needed it. With the online format we also had the option to have the workshop delivered by the same people, thereby increasing uniformity amongst workshops.

After all these difficulties, we managed to evidence that whilst national student confidence was low when addressing patient mental health, the workshop was an effective beneficial intervention! This knowledge is of benefit to dental research as it evidences how, if we are appropriately educated, we can improve patient outcomes, better supporting and understanding those with poor mental health. You too can make such an input in the field of dental research; if you have an inkling of an idea or a more fleshed out question you want to explore, why not consider research alongside your degree? It can be as much of a benefit to yourself (via conferences, collaboration and project management) as it can be to others and our patients.

Top tips for research around studies.

Perform a literature review around your concept to identify gaps in research and to ensure thorough understanding of the field

Choose who to work with - as an undergraduate you will always need a supervisor, but do you want to work with others? This can split the workload but you must ensure everyone is appropriately credited

Consider what impact your research could have and design your methodology appropriately to ensure your data answers your research question

If you want to collaborate with other schools and do a larger study, you can reach out via DentSoc, BDSA or BDJ Student

Be prepared to adapt and make changes as you go, things will not always go to plan!

- 1. Mental Health Foundation. Fundamental Facts About Mental Health. [ebook] London: Mental Health Foundation. 2016. Available at: https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/publications/fundamental-facts-about-mental-health-2016 (Accessed July 2021).

- 2. Freeman R. Have dentists a role in identifying mentally ill patients? Br Dent J 2001; 191: 621.

- 3. Preparing for Practice: Dental Team Learning Outcomes for Registration (2015 Revised Edition). General Dental Council.

- View on publisher site

- PDF (483.2 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

- Account Login

Science at the ADA

Innovative research for clinical decision making, critical policy information and oral health care performance measures.

What are some good research topics for dental students?

Dr. Bella Hayes

Popular Articles

Never miss a post, share this article, recent faqs, what are the advantages of digital marketing for dental practices, what are the steps to becoming a dental lab technician, what are the advantages of choosing a career in dental public health, what are the benefits of pursuing a dental career in public health, what are the career opportunities for dentists who want to work for international organizations, what are the job prospects for dental graduates who specialize in periodontics, people also asked.

What is the minimum high school GPA required to become a dentist?

Does dental school use your GPA from college or high school?

Can I get into dental school with a 3.35 GPA and 21 on DAT?

Is becoming a dentist a good career choice?

What is the process of becoming a dentist?

How long does it take to get a dentist degree?

What are some tips for coming up with a clever title for a research paper on dentistry?

What should I study before dental school?

Dentistry guidelines articles.

How to Choose the Right Dental School for You: Important Factors to Consider

Best Books for Dental Students: Recommendations for Success in Academics and Beyond

Navigating Dental Board Exams: How to Prepare and Succeed in Your Licensure Journey

Enhancing Your Dentistry Career: Exploring Dental Research Opportunities

Login to dentistry guidelines.

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Evidence Based Dental Care: Integrating Clinical Expertise with Systematic Research

Mallika kishore, sunil r panat, ashish aggarwal, nupur agarwal, nitin upadhyay, abhijeet alok.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

NAME, ADDRESS, E-MAIL ID OF THE CORRESPONDING AUTHOR: Dr. Mallika Kishore, Post Graduate Student, Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology, Institute of Dental Sciences, Bareilly, UP, India. Phone: 09719858806, E-mail: [email protected]

Received 2013 May 31; Revision requested 2013 Nov 24; Accepted 2013 Dec 19; Issue date 2014 Feb.

Clinical dentistry is becoming increasingly complex and our patients more knowledgeable. Evidence-based care is now regarded as the “gold standard” in health care delivery worldwide. The basis of evidence based dentistry is the published reports of research projects. They are, brought together and analyzed systematically in meta analysis, the source for evidence based decisions. Activities in the field of evidence-based dentistry has increased tremendously in the 21 st century, more and more practitioners are joining the train, more education on the subject is being provided to elucidate the knotty areas and there is increasing advocacy for the emergence of the field into a specialty discipline. Evidence-Based Dentistry (EBD), if endorsed by the dental profession, including the research community, may well- influence the extent to which society values dental research. Hence, dental researchers should understand the precepts of EBD, and should also recognize the challenges it presents to the research community to strengthen the available evidence and improve the processes of summarizing the evidence and translating it into practice This paper examines the concept of evidence-based dentistry (EBD), including some of the barriers and will discuss about clinical practice guidelines.

Keywords: Evidence based medicine, Dentistry, Dental care, Dental education

Introduction

The practice of dentistry presents many challenges on a daily basis. Keeping up with new materials and techniques, dealing with the numerous demands of running a small business, and meeting a variety of professional obligations, all compete for our time and attention [ 1 ]. As healthcare providers, it is important that physicians and dentists offer the best possible care for their patients. This requires not only a sound educational base but also a good source of current best evidence to support their treatment recommendations [ 2 ]. To do it successfully, certain skills need to be obliviously acquired, being the intention of evidence-based dentistry the providing better information for the clinician, improved treatment for the patient, and consequently an increased standing of the profession [ 3 ].In many countries, there has been increasing concern about the use of Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) in oral health care [ 4 ].The principles and methods of evidence based dentistry give dentists the opportunity to apply relevant research findings to the care of their patients. The key to finding evidence is to start with a focused, well-built clinical question [ 5 ]. Evidence-based oral health care includes the search for the best evidence, critical evaluation of the evidence, and integration of the evidence with the practitioner’s experience and expertise. Therefore, dental educators, dental students, and dental practitioners need to be aware of the uncertainties surrounding scientific evidence, the ways that the results of clinical studies are collected and analyzed, and the importance of unbiased research on which to base clinical decision making [ 6 ].

A goal of Healthy People 2010 is to promote the oral health of 50% of the nation’s children by applying sealants to their molar teeth. Unfortunately, just 32% of children aged 6 to 19 years have sealants. This may be due to the relatively slow translation of current biomedical science into dental practice [ 7 ].

The need for valid and current information for answering everyday clinical questions is growing. Ironically, the time available to seek the answers seems to be shrinking. In addition, a surprising amount of published research “belongs in the bin”[ 8 ] .

Evidence-based dentistry (EBD) closes the gap between clinical research and real world dental practice and provides dentists with powerful tools to interpret and apply research findings [ 9 ]. In dentistry, the evidence-based movement is at a relatively early stage of development. In addition to collating guidelines on effective care, it is critically important to understand what factors will influence dentists’ ability to change their clinical practices to incorporate the evidence. Without an understanding of how dentists change their clinical practices, evidence-based dentistry will achieve little [ 10 ].Therefore, it is crucial to implement evidence from research into clinical practice, and by doing this, the concept of EBD can become practically relevant to the dentist [ 11 ].

Evidence Based Dentistry

According to Azarpazhooh A et al., Evidence-based practice is a process of lifelong, self-directed learning in which providing health care creates the need for important information about diagnosis, prognosis, treatment, and other clinical and health care issues [ 12 ]. The American Dental Association’s definition is by far the most comprehensive, as it captures the core elements of EBD. They define it as “an approach to oral health care that requires the judicious integration of systematic assessments of clinically relevant scientific evidence, relating to the patient’s oral and medical condition and history, with the dentist’s clinical expertise and the patient’s treatment needs and preferences” [ 13 ]. It is a widely accepted term in the medical fields around the world. It can be defined as “the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients”[ 14 ].

Evidence-based practice (EBP) is said to be the current best approach to provide interventions that are scientific, safe, efficient and cost effective. The reasons for this are assumed to be through improvements in physicians’ and dentists’ skills and knowledge, as well as in the communication between patients and their physicians about the rationale behind clinical recommendations made. While studies have attempted to assess the levels of awareness and implementation of EBD amongst various groups of clinicians in different settings, it is not possible to generalize the results to all clinicians [ 2 , 15 ]. Evidence is based on the existence of at least one well-conducted randomized control trial (RCT) [ 16 ]. When asked about evidence-based practice, general dentists have a problem with the words themselves. The word “base” conjures an image of fundamental change. It implies a change in an essential entity, a foundation, something the practitioner cannot do without. The word “evidence” also causes a problem, because it has not been part of the vocabulary of clinical practice. It may conjure fear, because it relates to legal and regulatory matters. Evidence is what lawyers bring before a judge and jury in the pursuit of truth and justice [ 17 ].

Concept of Evidence Based Dentistry

In understanding the concept of EBD, it is helpful to clarify what it is not. It is not a “cookbook” approach to practice. EBD requires the integration of the best evidence with clinical expertise and patient preferences and, therefore, it informs, but never replaces, clinical judgement. Evidence-based health care recognizes the complex environment in which clinical decisions are made and the importance of individual patient circumstances, beliefs, attitudes and values[ 17 ]. Evidence-based practice is a practical approach to clinical problems. It involves tracking down the best available evidence, assessing its validity and using “rules of evidence” to grade the evidence according to its strength [ 18 ].

Evidence based dentistry does not mean clinicians abandon everything they learned in dental school. It does not force clinicians to go backwards to justify things the profession universally accepts [ 19 ].

Goals of Evidence Based Dentistry

Evidence-based dentistry has two main goals: best evidence/research, and the transfer of this in practical use. This involves four basic phases: Asking evidence-based questions (framing an answerable question from a clinical problem); Searching for the best evidence; Reviewing and critically appraising the evidence; Applying this information in a way to help the clinical practice [ 20 ]. An additional phase has been suggested that is the evaluation of performance of the techniques, procedures or materials [ 21 ].Evidence-based practice involves tracking down the available evidence, assessing its validity and then using the “best” evidence to inform decisions regarding care. Rules of evidence have been established to grade evidence according to its strength [ 5 ].

Steps in Practising Evidence Based Dentistry

In traditional dental care, emphasis is placed on the dentist’s accumulated knowledge and experience, adherence to accepted standards, and the opinion of experts and peers. Evidence-based practice, in contrast, places a premium on using current evidence to solve clinical questions [ 22 ].It presupposes two things about the dentist: one, that he or she is conversant with the current literature, and two, that he or she is competent to evaluate it. The first requires that dentists read the scientific literature, particularly in clinical research, and the second requires that they can critically appraise the literature. Niederman and Badovinac [ 23 ] identify five steps in clinical decision making that the evidence-based dentist must be involved in:

1) Converting clinical information needs into an answerable question

2) Using electronic databases to find available evidence

3) Critically appraising the evidence for validity and importance

4) Integrating the appraisal with the patient’s perceived needs and applying these results in clinical practice

5) Evaluating their own performance

Awareness of Evidence Based Dentistry Among the Dentists

There have been various studies performed to study the awareness of dentists regarding the evidence based dentistry. In a study done in Kuwait it was concluded that the overall awareness of EBD amongst dentists was low, even though more than half of them reported that they generally practise it [ 2 ].

Similar study carried out among the general dental practitioners currently practising in the North West of England and it was found that only 29% (60/204) could correctly define the term EBP. When faced with clinical uncertainties 60% (122/204) of general dental practitioners turned to friends and colleagues for help and advice. Eighty one percent of respondents were interested in finding out further information about EBP (165/204) [ 9 ].

Other studies carried out to evaluate evidence-Based Practice among a group of Malaysian Dental Practitioners and response rate was 50.3 percent [ 14 ].

Clinical Practice Guidelines

Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs) are “systematically developed statements to assist practitioners and patients in arriving at decisions on appropriate health care for specific clinical circumstances.”[ 1 ].

Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (EB-CPGs) are structured and formal, and use rigorous, explicit and reproducible methods to assemble and evaluate the evidence. These guidelines are based on systematic reviews and incorporate values and preferences of patients and practitioners. The process of creating a well-developed EB-CPG includes external review and comment by those who will be using the guidelines - for example, a wide range of clinicians, as well as patients or their representatives [ 24 ].

The development of EB-CPGs in dentistry is in the beginning stages. A review in 1995 of guideline development by various dental organizations and specialties in the United States revealed a lack of systematic analysis of the literature.

Implementing Evidenced Based Dentistry in Clinical Practise

Learning involves identifying and evaluating new methods that might improve care and prognosis, determining when to implement those that appear to improve care, and discarding old diagnostics and therapeutics that prove to be unsound [ 25 ]. In this information age, it is not uncommon for a patient to rush home from the dentist’s office to look up on the Internet or in health reference texts the drug or diagnosis that was provided. Science in the form of statistical evidence is being introduced into everyday language through advertising [ 16 ]. However, some studies have demonstrated that EBD, when taught only in the classroom, may have little impact on the attitudes or behaviors of clinical practitioners. In other words, theoretical knowledge of EBD, obtained without opportunities to practice using an evidence-based approach to patient care decision making, may lead to no changes in dental practice at all. Therefore, it is crucial to implement evidence from research into clinical practice, and by doing this, the concept of EBD can become practi¬cally relevant to the dentistry [ 11 ].

Although considerable resources are spent on clinical research, little attention has been paid to the implementation of research evidence into clinical care [ 10 ]. EBP may not be a concept that every dentist is familiar with, but increasing consumer pressures and the present economic, social, and political changes, will necessarily demand that evidence based principles are implemented [ 9 ].

Searching For the Best Evidence

Practitioners can access computerize bibliographic database such as MEDLINE for references either online via the Internet or in a CD-ROM format [ 26 ]. Below are some essential online resources for evidence based research.

PubMed is a free medical database provided by the U.S. National Library of Medicine and the National Institutes of Health (NLM). Highly authoritative and up-to-date, PubMed gives you access to MEDLINE, NLM’s database of citations and abstracts in the fields of medicine, nursing, dentistry, veterinary medicine, health care systems and preclinical sciences. Updated daily, Pub Med gives you access to over 14 million citations dating back to the 1950s. Records are indexed using the NLM’s Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) [ 13 ].

The Cochrane Collaboration

The Cochrane Collaboration is an international organization whose overall aim is to b;uild and maintain a database of up-to-date systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials of health care and to make these readily accessible electronically. It has been called “an enterprise that rivals the Human Genome Project in its potential implications for modern medicine” [ 27 ] and has also been described as being one of the most significant clinical advances since the creation of the National Institutes of Health in the U.S [ 13 ].

Barriers to Implementing Evidence-Based Clinical Practise

In many countries, there has been increasing concern about the use of evidence-based practice (EBP) in oral health care. The call for the implementation of EBP to increase the effectiveness of dental care seems to face many obstacles [ 4 ].

Potential Barriers to Change

1) Environmental: a) In the practice: There are limitations of time and organisation of the practice (for example, a lack of disease registers or mechanisms to monitor repeat prescribing).

b) In education: Due to inappropriate continuing education and failure to connect with program to promote better quality of life. There is lack of incentives to participate in effective educational activities.

c) In health care: Due to lack of financial resources and defined practice populations. Ineffective or unproved activities promoted by health policies. Failure to provide practitioners with access to appropriate information.

d) In society : Due to influence of the media on patients in creating demands or beliefs. There is impact of disadvantage on patients’ access to care.

2) Personal

a) Factors associated with the practitioner

Due to obsolete knowledge and influence of opinion leaders (such as health professionals whose views influence their peers) along with beliefs and attitudes (for example, a previous adverse experience of innovation).

b) Factors associated with the patient

There are demands for care by the patient and perceptions or cultural beliefs about appropriate care [ 28 ].

A qualitative study was carried out to assess the obstacles among the Flemish (Belgian, Dutch-speaking) dentists experience in the implementation of EBP in routine clinical work. Three major categories of obstacles were identified. These categories relate to obstacles in

1) Evidence,

2) Partners in health care (medical doctors, patients, and government),

3) Field of dentistry.

Their findings suggested that educators should provide communication skills to aid decision making, address the technical dimensions of dentistry, promote lifelong learning, and close the gap between academics and general practitioners (dentists) in order to create mutual understanding [ 4 ].

The most common barriers to implementation of early-adopting dentists are difficulty in changing current practice model, resistance and criticism from colleagues, and lack of trust in evidence or research [ 7 ].

In an article noted that “dentistry is stunningly inexact science.” It is therefore becoming increasingly clear in this “age of Information” that investigative journalism and consumer activism render all clinical decision-making subject to external scrutiny rather than to just professional or peer-review as in the past [ 29 ].

Current Status of Clinically Relevant Evidence in Dentistry

The translation of research into practice assumes that clinically relevant evidence is available. Unfortunately, in light of the billions of dollars invested in dental research during the last five decades in Europe and the US, the dental research community has paid relatively little attention to clinical aspects of care. Consequently, and contrary to the situation in medicine, there are relatively few randomized controlled trials and other outcomes oriented studies in dentistry that have evaluated clinically relevant interventions. For example, there are no clinical trials that have compared the outcomes of different methods of caries diagnosis using relevant outcome measures. Also, no outcome studies are available for disease-based management of dental caries, periodontal diseases, or facial pain [ 30 ].

The evidence needed for evidence-based dentistry must include a broader range of outcomes, including those considered important by patients. For example, a classic definition of appropriateness indicates that treatment is deemed appropriate when the expected health benefit exceeds the expected negative consequences by a sufficiently wide margin that the treatment is worth doing [ 31 ].

Benefits of Evidence Based Practise

There are some advantages of evidence based practice [ 32 ] [ Table/Fig-1 ].

[Table/Fig-1]:

Advantages of evidence based dental practise

Evidence-based dentistry does offer the opportunity for the practice of dentistry to enter a new era, it is worth recalling an old maxim— “the trouble with opportunity is it always comes disguised as hard work.” Educators have an important role to play in providing communication skills to aid decision making, addressing the technical dimensions of dentistry, promoting lifelong learning, and closing the gap between academics and general dentists in order to create mutual understanding The ultimate goal would be assisting dental students in learning the skills to practice evidence-based dentistry so that they can provide their future patients with the best clinical evidence and judgment for optimal and cost-effective dental care. There is, therefore, a need to apprise current practitioners on the new method of thinking. Dentistry needs to make strides to keep pace with the prevailing paradigm of evidence-based care. There is a strong “need for the science behind our treatment decisions”.

Financial or Other Competing Interests

- [1]. Sutherland SE. The building blocks of evidence-based dentistry. J Can Dent Assoc. 2000;66:241–4. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [2]. Haron IM, Sabti MY, Omar R. Awareness, knowledge and practice of evidence-based dentistry amongst dentists in Kuwait. Eur J Dent Educ. 2012;16:e47–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0579.2010.00673.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [3]. Ballini A, Capodiferro S, Toia M, Cantore S, Favia G, De Frenza G, et al. Evidence-based dentistry: what’s new? Int J Med Sci. 2007;4:174–8. doi: 10.7150/ijms.4.174. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [4]. Hannes K, Norré D, Goedhuys J, Naert I, Aertgeerts B. Obstacles to implementing evidence-based dentistry: a focus group-based study. J Dent Educ. 2008;72:736–44. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [5]. Sutherland SE. Evidence-based dentistry: Part IV. Research design and levels of evidence. J Can Dent Assoc. 2001;67:375–8. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [6]. Crawford JM, Briggs CL, Engeland CG. Publication bias and its implications for evidence-based clinical decision making. J Dent Educ. 2010;74:593–600. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [7]. Spallek H, Song M, Polk DE, Bekhuis T, Frantsve-Hawley J, Aravamudhan K. Barriers to implementing evidence-based clinical guidelines: a survey of early adopters. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2010;10:195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jebdp.2010.05.013. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [8]. Sutherland SE. Evidence-based dentistry: Part V. Critical appraisal of the dental literature: papers about therapy. J Can Dent Assoc. 2001;67:442–5. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [9]. Iqbal A, Glenny AM. General dental practitioners’ knowledge of and attitudes towards evidence based practice. Br Dent J. 2002;193:587–91. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4801634. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [10]. McGlone P, Watt R, Sheiham A. Evidence-based dentistry: an overview of the challenges in changing professional practice. Br Dent J. 2001;190:636–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4801062. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [11]. Faggion CM Jr, Tu YK. Evidence-based dentistry: a model for clinical practice. J Dent Educ. 2007;7:825–31. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [12]. Azarpazhooh A, Mayhall JT, Leake JL. Introducing dental students to evidence-based decisions in dental care. J Dent Educ. 2008;72:87–109. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [13]. Rabb-Waytowich D. You ask, we answer:Evidence-based dentistry: Part 1. an overview. J Can Dent Assoc. 2009;75:27–8. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [14]. Yusof ZY, Han LJ, San PP, Ramli AS. Evidence-based practice among a group of Malaysian dental practitioners. J Dent Educ. 2008;72:1333–42. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [15]. Haj-Ali RN, Walker MP, Petrie CS, Williams K, Strain T. Utilization of evidence-based informational resources for clinical decisions related to posterior composite restorations. J Dent Educ. 2005;69:1251–6. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [16]. Beyers RM. Evidence-based dentistry: a general practitioner’s perspective. J Can Dent Assoc. 1999;65:620–2. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [17]. Browman GP. Evidence-based paradigms and opinions in clinical management and cancer research. Semin Oncol. 1999;26:9–13. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [18]. Sackett DL. Rules of evidence and clinical recommendations for the management of patients. Can J Cardiol. 1993;9:487–9. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [19]. Goldstein GR. What is evidence based dentistry? Dent Clin North Am. 2002;46(1-9):v. doi: 10.1016/s0011-8532(03)00044-2. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [20]. Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ. 1996;312:71–2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [21]. Carr AB, McGivney GP. Users’ guides to the dental literature: how to get started. J Prosthet Dent. 2000;83:13–20. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [22]. Coulter ID. Evidence-based dentistry and health services research: is one possible without the other? J Dent Educ. 2001;65:714–24. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [23]. Niederman R, Badovinac R. Tradition-based dental care and evidence-based dental care. J Dent Res. 1999;78:1288–91. doi: 10.1177/00220345990780070101. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [24]. Jadad A. Randomized controlled trials. London: BMJ Books; 1998. From individual trials to groups of trials: reviews, meta-analyses and guidelines; pp. 78–92. [ Google Scholar ]

- [25]. Marinho VC, Richards D, Niederman R. Variation, certainty, evidence, and change in dental education: employing evidence-based dentistry in dental education. J Dent Educ. 2001;65:449–55. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [26]. Nainar SM. Evidence-based dental care-a concept review. Pediatr Dent. 1998;20:418–21. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [27]. Naylor CD. Grey zones of clinical practice: some limits to evidence-based medicine. Lancet. 1995;345:840–2. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92969-x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [28]. Haines A, Donald A. Making better use of research findings. BMJ. 1998;317:72–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7150.72. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [29]. Ecenbarger W. How honest are dentists? Reader’s Digest. February, 1997;150:50–56. [ Google Scholar ]

- [30]. Dickersin K, Manheimer E. The cochrane collaboration: evaluation of health care and services using systematic reviews of the results of randomized controlled trials. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1998;41:315–31. doi: 10.1097/00003081-199806000-00012. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [31]. Bader J, Ismali A, Clarkson J. Evidence-based dentistry and the dental research community. J Dent Res. 1999;78:1480–3. doi: 10.1177/00220345990780090101. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- [32]. Merijohn GK, Bader JD, Frantsve-Hawley J, Aravamudhan K. Clinical decision support chairside tools for evidence-based dental practice. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2008;8:119. doi: 10.1016/j.jebdp.2008.05.016. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (90.8 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Current Research in Dentistry

Aims and scope.

Current Research in Dentistry cover articles on evaluation, diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of diseases, disorders and conditions of the soft and hard tissues of the jaw, the oral cavity, maxillofacial area and the adjacent and associated structures and their impact on the human body. Current Research in Dentistry is an international, peer reviewed journal publish two times a year.

It is with great pleasure that we announce the SGAMR Annual Awards 2020. This award is given annually to Researchers and Reviewers of International Journal of Structural Glass and Advanced Materials Research (SGAMR) who have shown innovative contributions and promising research as well as others who have excelled in their Editorial duties.

This special issue "Neuroinflammation and COVID-19" aims to provide a space for debate in the face of the growing evidence on the affectation of the nervous system by COVID-19, supported by original studies and case series.

The SGAMR Editorial Board is pleased to announce the inauguration of the yearly “SGAMR Young Researcher Award” (SGAMR-YRA). The best paper published by a young researcher will be selected by a journal committee, from the Editorial Board.

- Recently Published

- Most Viewed

- Most Downloaded

Doctor of Science in Dental Research/Dentistry

Application Procedures

There are two routes of entry to the TUSDM Doctor of Science program:

- Candidates who are applying to the Doctor of Science program only

- Candidates who apply to a joint Doctor of Science/Advanced Education program in Orthodontics, Periodontics, Prosthodontics, Endodontics or Pediatric Dentistry

Applicants must hold an approved dental degree (DDS, DMD, or BDS), and may or may not be interested in dental specialization. Evidence of excellent scholarship, research potential, and a career interest in academic dentistry must be demonstrated.

Doctor of Science Candidate Only

Candidates may pursue the Doctorate of Science (DSc) degree without participating in an Advanced Education specialty certificate program. Candidates must submit a complete application to the TUSDM Office of Admissions. A complete application includes a brief essay (300 to 500 words) describing the candidate’s research experience, reasons for wanting to pursue the DSc in Dental Research, and research topic ideas. TOEFL score, if applicable, are required. DSc-only candidates must apply by March 1 in order to matriculate on July 1 of that same year.

Joint Program Candidates

Candidates interested in jointly pursuing a Doctorate of Science (DSc) degree and participating in an Advanced Education specialty certificate program must indicate this in their application and letter of intent. A complete application includes a brief essay (300 to 500 words) describing the candidate’s research experience, reasons for wanting to pursue the DSc in Dental Research, and research topic ideas. Note: Candidates must submit a separate application to their preferred Advanced Education specialty program. Deadlines for joint programs vary depending on the specialty.

Applications are reviewed on a case-by-case basis. Depending on admission decisions, candidates may be admitted to the DSc-only or specialty-only program.

Students enrolled in the DSc-only program are charged at the customary post-graduate tuition rate for three years. Students enrolled in a joint DSc/Advanced Education specialty certificate program are charged at the customary post-graduate tuition rate the first two years, then they are also charged an additional 25% of the customary post-graduate tuition rate for each semester they are concurrently enrolled in both programs.

The proposed DSc curriculum and program delivery are designed to include two tracks.

Track 1: DSc only – three years to completion

Track 2: DSc + dental specialty – five years to completion

- Year 1 and 2 – Courses and development of research proposal and execution of research project

- Year 3, 4, and 5 – Students will begin their specialty programs and department-specific courses, e.g., periodontology, etc.

The first two years are identical for both tracks. Students will complete core coursework, an oral qualifying exam, a research proposal, and applicable electives guided by their research interests and thesis topic. Students will also perform independent research and study, presenting their culminating work in a thesis defense.

Research Methods in Dentistry

- © 2022

- Fahimeh Tabatabaei 0 ,

- Lobat Tayebi ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1947-5658 1

School of Dentistry, Marquette University, Milwaukee, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

- Presents guidelines to overcoming research challenges faced by students

- Provides comprehensive coverage of all aspects of dental research

- Covers ethics in research—in animal as well as human studies

7581 Accesses

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this book

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Other ways to access

Licence this eBook for your library

Institutional subscriptions

About this book

Similar content being viewed by others.

The recent ethics boom in dentistry—moral fig leaf, fleeting trend or professional awakening?

Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry

How evidence-based is dentistry anyway? From evidence-based dentistry to evidence-based practice

- Biomedical research

- Dental research

- Evidence-based Research

- Medical Research

- Research ethics

- Research design

- Research methods

- Research proposal

- Research writing

- Responsible Conduct of Research

- Technical research

Table of contents (7 chapters)

Front matter, introduction to dental research.

Fahimeh Tabatabaei, Lobat Tayebi

Design Cycle of Research

Systematic review and evidence-based research in dentistry, writing a research proposal, scientific/clinical research report, reference management in scientific writing, ethics in dental research, back matter, authors and affiliations, about the authors.

Fahimeh Tabatabaei, DDS, Ph.D., is a dentist and a postdoctoral fellow at Marquette University School of Dentistry, Milwaukee, WI. She studied in the fields of oral biology and dental biomaterials at Toulouse University in France, and in 2010 was awarded her Ph.D. in Dental Biomaterials by Tehran University of Medical Sciences. Dr. Tabatabaei has published more than 60 peer-reviewed journal articles and book chapters. She was Associate Professor and Head of the Dental Biomaterials Department at the National University of Iran (SBMU), where she supervised two Ph.D. theses and mentored many dental students. She taught courses on research methodology for dental students and residents for years and authored the book Research Methods in Dentistry in Persian (Noordanesh Publisher, 2013).

Lobat Tayebi, Ph.D., is an Associate Professor and Director of Research at Marquette University School of Dentistry. She is a researcher in materials science and regenerative dentistry with multiple patents in the field. Her publication list comprises more than 320 articles . She teaches the Research Methods in Dentistry course at Marquette and has mentored more than 80 DDS students, residents, researchers, graduate students, and postdocs who are highly productive in research.

Bibliographic Information

Book Title : Research Methods in Dentistry

Authors : Fahimeh Tabatabaei, Lobat Tayebi

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-98028-3

Publisher : Springer Cham

eBook Packages : Engineering , Engineering (R0)

Copyright Information : The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2022

Hardcover ISBN : 978-3-030-98027-6 Published: 10 April 2022

Softcover ISBN : 978-3-030-98030-6 Published: 11 April 2023

eBook ISBN : 978-3-030-98028-3 Published: 09 April 2022

Edition Number : 1

Number of Pages : XIII, 165

Number of Illustrations : 35 b/w illustrations, 5 illustrations in colour

Topics : Biomedical Engineering and Bioengineering , Dentistry , Research Skills , Biomedical Engineering/Biotechnology

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Open access

- Published: 22 June 2023

Patients’ perspectives on the use of artificial intelligence in dentistry: a regional survey

- Nasim Ayad 1 ,

- Falk Schwendicke 2 ,

- Joachim Krois 2 ,

- Stefanie van den Bosch 3 ,

- Stefaan Bergé 3 ,

- Lauren Bohner 1 ,

- Marcel Hanisch 1 na1 &

- Shankeeth Vinayahalingam 1 , 3 na1

Head & Face Medicine volume 19 , Article number: 23 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

7188 Accesses

11 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

The use of artificial intelligence (AI) in dentistry is rapidly evolving and could play a major role in a variety of dental fields. This study assessed patients’ perceptions and expectations regarding AI use in dentistry. An 18-item questionnaire survey focused on demographics, expectancy, accountability, trust, interaction, advantages and disadvantages was responded to by 330 patients; 265 completed questionnaires were included in this study. Frequencies and differences between age groups were analysed using a two-sided chi-squared or Fisher’s exact tests with Monte Carlo approximation. Patients’ perceived top three disadvantages of AI use in dentistry were (1) the impact on workforce needs (37.7%), (2) new challenges on doctor–patient relationships (36.2%) and (3) increased dental care costs (31.7%). Major expected advantages were improved diagnostic confidence (60.8%), time reduction (48.3%) and more personalised and evidencebased disease management (43.0%). Most patients expected AI to be part of the dental workflow in 1–5 (42.3%) or 5–10 (46.8%) years. Older patients (> 35 years) expected higher AI performance standards than younger patients (18–35 years) ( p < 0.05). Overall, patients showed a positive attitude towards AI in dentistry. Understanding patients’ perceptions may allow professionals to shape AI-driven dentistry in the future.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI) have led to tremendous changes and challenges in the field of dentistry [ 1 ]. AI describes the theorisation and development of computer systems (e.g., neural networks) aiming to imitate the human intellect [ 2 ]. These networks are composed of many layers that transform input data (e.g., images) into outputs (e.g., disease presence/absence), allowing a wide range of possible applications from automated treatment planning to improved diagnostics [ 3 ].

In the near future, AI could play a major role in nearly every part of dentistry, including oral and maxillofacial surgery, cariology and endodontics, periodontics, paediatric dentistry, orthodontics and prosthodontics [ 2 ].

The image analysis of dental X-rays could be considered as the most important possible function of AI in dentistry. The frequent use of intraoral and panoramic images underlines the importance of the imaging sector in dentistry. Recently, AI has shown promising results in the analysis of dental X-rays in various studies [ 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ]. The first Food and drug Adminisration (FDA) approved/ Conformité Européenne (CE) marked AI solutions are currently entering the market and the clinical arena [ 8 ].

Nevertheless, a range of challenges still require solutions. The technical complexity of modelling patient data to tailor medical decisions increases exponentially with the confronted uncertainties and erroneous data used in clinical decision making [ 9 ]. The limited availability of data, poor methodological reproducibility and the narrow usability of current AI systems are the three main reasons why AI has not yet become a major assistive technological system in dentistry [ 10 ]. Moreover, ethical and legal challenges remain; debates around data privacy, safety and effectiveness or liability are still ongoing. Open public and political discussions are desired to rethink the current regulatory frameworks and ensure they can be adapted to the healthcare system [ 11 ]. However, the extent to which AI solutions are adapted in dentistry will mainly depend upon the attitudes of clinicians and patients [ 12 ].

Few studies have investigated dentists’ and dental students’ attitudes and perceptions towards AI [ 13 , 14 , 15 ]. These studies shared optimistic views, with a positive impact on dental care. One recent controlled study assessed patients’ perspectives towards AI for radiographic caries detection and the impact of AI-based diagnosis on patients’ trust [ 16 ]. Compared to Kosan et al., the current work addressed patients´ perspectives on AI in general.

Another study assessed patients’ perceptions of the use of AI in radiology and identified six key domains of patients’ perspectives: (1) proof of technology, (2) procedural knowledge, (3) competence, (4) efficiency, (5) personal interaction and (6) accountability [ 17 ].

The purpose of the present study was to assess patients’ knowledge and perceptions of AI in dentistry. This study was purely explorative, without concrete hypothesis testing. Understanding patients’ perceptions may allow dentists to shape AI-driven dentistry in the future.

Materials and methods

A modified 18-item questionnaire in the German language (Table 1 ) was used based on the survey design by Scheetz et al. [ 12 ]. The survey questions focused on demographics, self-perceived dental health, expectancy, accountability, trust, interaction, advantages and disadvantages. The survey questions were validated through a literature review and pilot testing. Disagreements regarding any questions were resolved by consensus (NA, LB, MH). To avoid any potential discrimination, questions regarding gender or education were omitted. The inclusion criteria were a minimum age of 18 and fluent proficiency in German. Approval for this survey was granted by the Ethics Committee of the Westphalia-Lippe Medical Association, Westfälische-Wilhelms University Münster (IRB approval no. 2021–616-f-S). This study was conducted in accordance with the code of ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Sample size

Sample size estimation and power calculations were waived by the Institute of Biostatistics and Clinical Research of Westfälische-Wilhelms University Münster. This study was purely explorative and observational, using convenience sampling without concrete hypothesis testing.

Study design

The cross-sectional questionnaire was distributed to patients who visited the outpatient clinic at the Department of Cranio-Maxillofacial Surgery, University hospital Münster, and a private dental clinic in Münster, Germany, between November 2021 and March 2022. These two clinics cover a broad range of clinical areas, such as implantology, oral surgery, reconstructive dentistry, prosthodontics, orthognathic surgery and periodontics. Participation was voluntary, and no incentives were provided. Written in-formed consent was obtained from each participant prior to the survey commencement.

All participating patients received an ethically approved information sheet with a written explanation of the anticipated use of AI in dentistry (e.g., intraoral scan segmentation and digital implant position design). For further clarity, the first AI application receiving CE marking in dentistry (dentalXrai Pro, dentalXrai GmbH, Berlin) was provided as an example.

Descriptive statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS Statistics Version 28.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Depending on the frequency, group differences were calculated using two-sided chi-squared or two-sided Fisher’s exact tests. An asymptomatic approximation using the Monte Carlo method was used in cases with invalid computational times. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

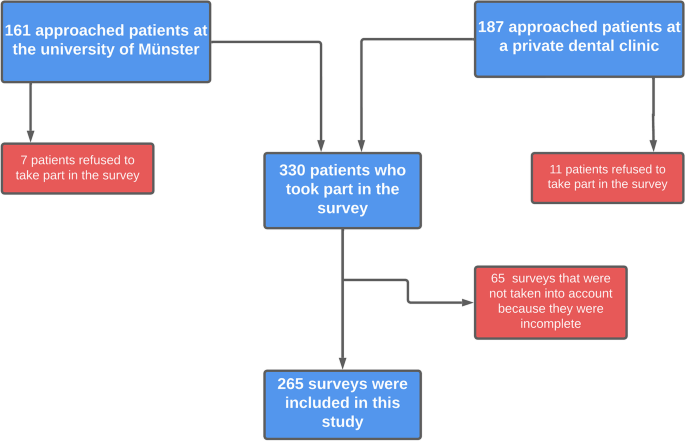

Of the 348 participants to whom the questionnaire was distributed, 18 (5.2%) refused to answer, and 265 answered the questionnaire completely. Sixty-five incomplete surveys were excluded from further analysis based on the exclusion criteria. The flowchart showing the survey distribution procedure is shown in Fig. 1 .

Flowchart showing the survey distribution procedure

The demographics and self-perceived dental health of the 265 patients are outlined in Table 2 .

Self-perceived knowledge of artificial intelligence

The majority of the patients ( n = 248, 93.6%) assessed their knowledge of digital technology as ‘average’ or ‘above average’. In comparison, only half of the participants ( n = 139, 52.5%) rated their knowledge of AI as ‘average’ or ‘above average’. In total, 47.5% ( n = 126) rated their knowledge of AI as ‘nothing’ or ‘below average’.

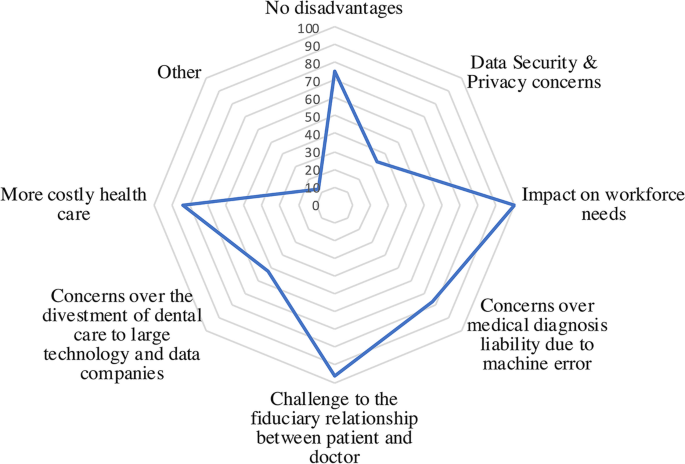

Disadvantages of using AI in dentistry

The top three disadvantages cited by patients regarding the use of AI in dentistry were (1) the impact on workforce needs (37.7%), (2) new challenges to the fiduciary relationship between dentist and patient (36.2%) and (3) increased dental care costs (31.7%) (Fig. 2 ). Additional expressed disadvantages were liability, neglect of education, limited applicability for older dentists and lack of empathy. Only 12.8% of the cases were perceived as having a data privacy disadvantage.

Cited Disadvantages of using AI in dentistry

Major advantages of AI in dentistry

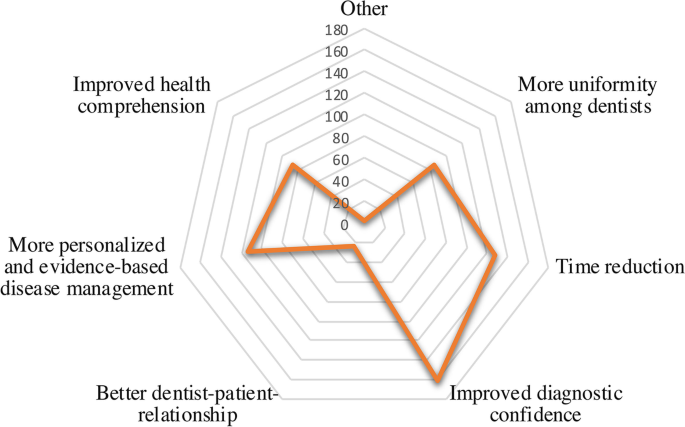

The top three advantages respondents perceived regarding the use of AI in dentistry were ‘improved diagnostic confidence’ (60.8%), followed by ‘time reduction’ (48.3%) and ‘more personalised and evidencebased disease management’ (43.0%) (Fig. 3 ). Another stated advantage was the dual-control principle. The dual-control-principle is a theory that requires for certain activities (i. e. decision making in diagnosing or treatment) at least two operators/systems in order to increase accuracy and transparency. In addition, the impact on the fiduciary relationship between the dentist and patient was considered an advantage by only 9.1% of respondents.

Cited Advantages of using AI in dentistry

Improvement in public oral health

Regarding whether the implementation of AI would lead to better public oral health, the majority ( n = 137, 51.7%) responded that they were unsure. About one-quarter of the volunteers ( n = 73, 27.5%) believed that public oral health would experience a major improvement due to the use of AI.

Hypothetical workflow for diagnosing dental x-rays

One possible future way of diagnosing intra and extraoral dental images could be as follows: Dental images will be analysed by an AI first and the findings will be assessed by the dentist afterwards. Of the respondents, 84.9% ( n = 225) agreed with this proposed procedure, while a minority (4.9%, n = 13) disagreed.

Acceptable AI performance standards and clinical workflows

Around half of the patients ( n = 125, 47.2%) stated that AI should perform better than an average-performing dentist, while 29.1% ( n = 77) expected AI to be as good as the best dentist. Only a minority (7.5%, n = 20) demanded that AI be better than the best performing dentist. Significant differences were seen between younger (18–35 years) and older (> 35 years) patients in terms of acceptable AI performance standards ( p < 0.05). Older patients expected higher AI performance standards. Around half of the respondents assumed that the use of AI could prevent mistakes made by dentists ( n = 129, 48.7%).

Expected time until AI will be part of dental workflows

Most patients expected that AI would be part of the dental workflows either in 1–5 ( n = 112, 42.3%) or 5–10 years ( n = 124, 46.8%) years. Only a tenth ( n = 21, 7.9%) expected AI integration 10 years or later. Furthermore, the majority ( n = 195, 73.6%) agreed with the following statement: ‘Dentistry will benefit from the use of artificial intelligence’.

The use of AI in dentistry is rapidly evolving and could play a major role in the dental office in the near future. As Chen et al. [ 18 ] pointed out, AI systems can be categorised into pre-, inter- and post-appointment AI systems. The idea of a comprehensive AI dental care system predicts that AI could play a role in patient management (pre-appointment) to analyse patients’ needs and risks, in diagnosis and treatment planning/decision and in outcome prediction (inter-appointment), as well as in labour work (e.g., design for prosthodontics) and treatment evaluation (post-appointment). This model emphasises the variety of tasks that AI could take part in. Nevertheless, the inter-appointment AI systems would be most visible to patients, as these systems would intervene in diagnosis, treatment decisions and planning.

The present survey assessed patients’ perceptions and attitudes towards AI in dentistry. Our findings are in line with previous surveys. The introduction of new technologies will lead to a shift in skill and expertise requirements. A consensus has arisen that education and training programmes need to be adjusted to labour market requirements [ 19 ]. Furthermore, surveys have highlighted disadvantages regarding employment prospects [ 20 , 21 ]. However, as other studies have pointed out, AI will rather work synergistically with clinicians than replace clinicians completely by overtaking clinical work [ 22 ]. The conclusion of other surveys that investigated the attitudes of dental students towards AI was that implementing AI in further dental training curricula is important [ 15 , 23 ].

AI-based communication often lacks intentionality and therefore constitutes a significant obstacle at the communication level. In line with these findings, previous studies have shown a preference for clinician based diagnostic decisions over AI-based diagnostic decisions [ 17 , 24 , 25 , 26 ]. Handing over parts of the communication to AI-driven systems as part of the diagnosis and treatment procedure can be crucial to the wellbeing of the patients and therefore the relationship between dentists and patients. Compared with the findings of this study, about a third of the participants stated that the use of AI in the dental field could arise new challenges to the fiduciary relationship between dentist and patient (36.2%). However, assistive AI systems should provide support to the dentist, which would enhance their ability to attend to higher valued tasks, such as more professional interactions with patients, integrating patients into the diagnosis and treatment process and being more visible to the clinical team and patients [ 27 ]. The dentist is constantly asked to nonverbally assess the patient’s feelings and adapt their further actions based on their evaluation [ 28 ]. Moreover, due to the fact that 330 patients took part in the survey and only eighteen patients have declined to do so, an enormous interest for AI in dentistry among dental patients is observable. This underlines the importance of such surveys in order to demonstrate the possibilities of AI implementation in the dental field for patients.

Lastly, AI-based dental care will raise new questions about cost-effectiveness and ever rising healthcare costs. About a third of the patients, that have participated in our survey concern about a possible raise of costs. However, Rossi et al. analysed cost-effectiveness using health economic modelling via Markov models and concluded that the current evidence supporting AI as a decision support mechanism is limited [ 29 , 30 ]. More investigation is needed.

Previous studies have referred to AI as a facilitator of faster, more precise and more personalised and evidence-based disease management. These studies have reported on par or even higher diagnostic accuracies than average dentists [ 8 , 10 , 31 ].

To be more precise, AI is mainly used in lesion segmentation in the fields of cariology and endodontics. Identifying tooth surface loss, root caries, periapical lesions or root fractures is crucial in further treatment decision-making. Depending on the diagnosis, the affected tooth may undergo tooth preserving/restorative treatment or, in the worst case, extraction. The treatment decision will have a major impact on further treatment requirements. Accurate and precise detection of lesions is important in the implementation of suitable treatments [ 32 ]. In terms of caries detection, numerous studies have reported that trained and validated AI systems have significantly higher accuracy and sensitivity than clinicians [ 8 , 29 , 32 , 33 ]. As the present study assessed the acceptable performance of AI, about half of the participant stated the AI systems should be better than an average dentist and could prevent mistakes made by the dentist. Compared with the studies that investigated the actual performance of AI, current AI-systems could live up the participants´ claim.

The detection of periapical lesions in endodontic treatment is essential for further treatment planning and the prediction of treatment success. Setzer et al. reported excellent results in identifying periapical lesions on Cone Beam Computer Tomography (CBCT) using a deep learning system based on an encoder-decoder architecture (U-NET) [ 34 ]. The application of such systems could lead to more reliability in diagnosis, with accuracy levels on par or even higher than experienced specialists [ 35 ].

Furthermore, the development of AI systems in the fields of oral and maxillofacial surgery is promising. AI systems may help in diagnosing the pathologies of various types of diseases and assist in treatment planning. Neural networks may be used to diagnose pathologies in the bone and mucosa, guiding orthognathic surgery, implantology and complication management [ 36 ]. For example, with an accuracy of 94%, a support vector machine (SVM) classifier system was able to differentiate between periapical cysts and keratocystic odontogenic tumours in CBCT scans [ 37 ]. In addition, diagnosing tumorous lesions at an early stage has a significant impact on disease treatment and outcomes. AI systems may have the ability to help professionals and mitigate healthcare delays [ 38 ]. In terms of orthognathic surgery, AI could play a major role from treatment planning to treatment follow-up. With the ability to visualise the treatment beforehand, confusion and misunderstanding by the patient may be limited [ 39 ].

In orthodontic treatment planning, the analysis of cephalometric radiographs is vital to successful treatments. The automated detection of landmarks by a knowledge-based algorithm showed no significant difference from manual detection [ 40 , 41 ]. Another study showed that a web-based deep learning application analysing 23 landmarks on cephalograms showed a classification success rate of 88.43% [ 42 ]. Camci et al. showed that a deep learning system that evaluated the tooth size of unerupted teeth had higher accuracy than the use of a Moyer’s table [ 43 ]. A scoping review stated the possibility of improving diagnostic accuracy in orthodontics using AI [ 44 ].

AI can also be used in paediatric dentistry. Numbering deciduous teeth in paediatric panoramic radiographs is crucial to identifying congenital or non-congenital issues. Recently, a convolutional neural network (CNN)-based system was able to detect deciduous teeth in panoramic radiographs with a sensitivity of 0.98 [ 45 ].

As the majority of the patients have stated that AI could lead to an improved diagnostic confidence, the opinion of most participants comes in the line with the studies that observed promising results regarding AI performance in the dental field. When it comes to an improved public oral health by using AI in dentistry, only about a quarter of the participants expect a major improvement. The authors conclude that more studies are needed to create awareness for AI-systems among patients.

Nevertheless, these models need to undergo a more transparent validation process using external data to verify their generalisability and reliability [ 46 ]. Due to the rapid development process, AI systems may be considered black-box systems by critical users and consumers. Developers may need to stress the principles of these models in a more transparent manner to keep clinicians and patients engaged and to avoid trust issues [ 47 ]. As about half of the respondents (47.5%, n = 126) rated their knowledge of AI as ‘nothing’ or ‘below average’, integrating patients in the development process and creating greater insight into the medical AI world may lead to enhanced AI knowledge. Transparency in the developing process could lead to more trustworthiness among patients.

Furthermore, AI models have proven to be extremely time-efficient for certain tasks, such as image segmentation [ 6 ]. Yasa et al. used a CNN-based system to identify teeth in bitewing radiographs, which yielded promising results in terms of accuracy and time efficiency [ 48 ]. Improving the dental workflow and increasing diagnostic accuracy may lead to more efficient, personalised dentistry. Time-efficiency have also been stated to be a major advantage of using AI in dentistry by the participants of the study.

The present study has a range of strengths and limitations. First, it is one of the few studies that focused on the attitudes and expectations of patients towards AI in dental and maxillofacial fields. The representativeness of this explorative study should be regarded with caution for several reasons. Even though the sample size was reasonable, larger sample sizes are needed for in-depth subgroup analysis next to validated instruments. Furthermore, Germany is a high-income country and therefore higher oral care awareness can be expected. Future studies can then be tested with a concrete hypothesis in reference to this study.

Overall, patients showed a positive attitude towards the use of AI in dentistry. Major advantages were the increase in diagnostic confidence, time efficiency and more personalised disease management. To achieve an increase in knowledge about AI, the development of AI should be more transparent and visible to patients.

Availability of data and materials

The data used in this study can be made available from the corresponding author within the regulation boundaries for data protection.

Schwendicke F, Golla T, Dreher M, Krois J. Convolutional neural networks for dental image diagnostics: a scoping review. J Dent. 2019;91: 103226.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Mörch CM, Atsu S, Cai W, Li X, Madathil SA, Liu X, et al. Artificial intelligence and ethics in dentistry: a scoping review. J Dent Res. 2021;100:1452–60.

Vinayahalingam S, Goey R, Kempers S, Schoep J, Cherici T, Moin DA, et al. Automated chart filing on panoramic radiographs using deep learning. J Dent. 2021;115: 103864.

Choi E, Lee S, Jeong E, Shin S, Park H, Youm S, et al. Artificial intelligence in positioning between mandibular third molar and inferior alveolar nerve on panoramic radiography. Sci Rep. 2022;12:2456.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Lee S, Kim D, Jeong H-G. Detecting 17 fine-grained dental anomalies from panoramic dental radiography using artificial intelligence. Sci Rep. 2022;12:5172.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Angelis FD, Pranno N, Franchina A, Carlo SD, Brauner E, Ferri A, et al. Artificial intelligence: a new diagnostic software in dentistry: a preliminary performance diagnostic study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:1728.

Vinayahalingam S, Xi T, Bergé S, Maal T, de Jong G. Automated detection of third molars and mandibular nerve by deep learning. Sci Rep. 2019;9:9007.

Mertens S, Krois J, Cantu AG, Arsiwala LT, Schwendicke F. Artificial intelligence for caries detection: randomized trial. J Dent. 2021;115: 103849.

Holzinger A, Langs G, Denk H, Zatloukal K, Müller H. Causability and explainability of artificial intelligence in medicine. WIREs Data Min Knowl Discov. 2019;9:1312.

Google Scholar

Schwendicke F, Samek W, Krois J. Artificial intelligence in dentistry: chances and challenges. J Dent Res. 2020;99:769–74.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Gerke S, Babic B, Evgeniou T, Cohen IG. The need for a system view to regulate artificial intelligence/machine learning-based software as medical device. NPJ Digit Med. 2020;3:53.

Scheetz J, Rothschild P, McGuinness M, Hadoux X, Soyer HP, Janda M, et al. A survey of clinicians on the use of artificial intelligence in ophthalmology, dermatology, radiology and radiation oncology. Sci Rep. 2021;11:5193.

Sur J, Bose S, Khan F, Dewangan D, Sawriya E, Roul A. Knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions regarding the future of artificial intelligence in oral radiology in India: a survey. Imaging Sci Dent. 2020;50:193–8.

Yüzbaşıoğlu E. Attitudes and perceptions of dental students towards artificial intelligence. J Dent Educ. 2021;85:60–8.

Pauwels R, Del Rey YC. Attitude of Brazilian dentists and dental students regarding the future role of artificial intelligence in oral radiology: a multicenter survey. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2021;50:20200461.

Kosan E, Krois J, Wingenfeld K, Deuter CE, Gaudin R, Schwendicke F. Patients’ perspectives on artificial intelligence in dentistry: a controlled study. J Clin Med. 2022;11:2143.

Haan M, Ongena YP, Hommes S, Kwee TC, Yakar D. A qualitative study to understand patient perspective on the use of artificial intelligence in radiology. J Am Coll Radiol. 2019;16:1416–9.

Chen Y-W. Artificial intelligence in dentistry: current applications and future perspectives. Quintessence Int. 2020;51:248–57.

PubMed Google Scholar

Hazarika I. Artificial intelligence: opportunities and implications for the health workforce. Int Health. 2020;12:241–5.

Chockley K, Emanuel E. The end of radiology? Three threats to the future practice of radiology. J Am Coll Radiol. 2016;13:1415–20.

Pakdemirli E. Artificial intelligence in radiology: friend or foe? Where are we now and where are we heading? Acta Radiologica Open. 2019;8:205846011983022.

Article Google Scholar

Pethani F. Promises and perils of artificial intelligence in dentistry. Aust Dent J. 2021;66:124–35.

Bisdas S, Topriceanu C-C, Zakrzewska Z, Irimia A-V, Shakallis L, Subhash J, et al. Artificial intelligence in medicine: a multinational multi-center survey on the medical and dental students’ perception. Front Public Health. 2021;9: 795284.

Ongena YP, Haan M, Yakar D, Kwee TC. Patients’ views on the implementation of artificial intelligence in radiology: development and validation of a standardized questionnaire. Eur Radiol. 2020;30:1033–40.

Promberger M, Baron J. Do patients trust computers? J Behav Decis Making. 2006;19:455–68.

Önkal D, Goodwin P, Thomson M, Gönül S, Pollock A. The relative influence of advice from human experts and statistical methods on forecast adjustments. J Behav Decis Making. 2009;22:390–409.

Recht M, Bryan RN. Artificial intelligence: threat or boon to radiologists? J Am Coll Radiol. 2017;14:1476–80.

Shan T, Tay FR, Gu L. Application of artificial intelligence in dentistry. J Dent Res. 2021;100:232–44.

Schwendicke F, Rossi JG, Göstemeyer G, Elhennawy K, Cantu AG, Gaudin R, et al. Cost-effectiveness of artificial intelligence for proximal caries detection. J Dent Res. 2021;100:369–76.

Gomez Rossi J, Rojas-Perilla N, Krois J, Schwendicke F. Cost-effectiveness of artificial intelligence as a decision-support system applied to the detection and grading of melanoma, dental caries, and diabetic retinopathy. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5: e220269.

Warin K, Limprasert W, Suebnukarn S, Inglam S, Jantana P, Vicharueang S. Assessment of deep convolutional neural network models for mandibular fracture detection in panoramic radiographs. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2022;51(11):1488–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijom.2022.03.056 .

Lee J-H, Kim D-H, Jeong S-N, Choi S-H. Detection and diagnosis of dental caries using a deep learning-based convolutional neural network algorithm. J Dent. 2018;77:106–11.

Devlin H, Williams T, Graham J, Ashley M. The ADEPT study: a comparative study of dentists’ ability to detect enamel-only proximal caries in bitewing radiographs with and without the use of AssistDent artificial intelligence software. Br Dent J. 2021;231:481–5.

Setzer FC, Shi KJ, Zhang Z, Yan H, Yoon H, Mupparapu M, et al. Artificial intelligence for the computer-aided detection of periapical lesions in cone-beam computed tomographic images. J Endod. 2020;46:987–93.

Aminoshariae A, Kulild J, Nagendrababu V. Artificial intelligence in endodontics: current applications and future directions. J Endod. 2021;47:1352–7.

Ossowska A, Kusiak A, Świetlik D. Artificial intelligence in dentistry-narrative review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:3449.

Yilmaz E, Kayikcioglu T, Kayipmaz S. Computer-aided diagnosis of periapical cyst and keratocystic odontogenic tumor on cone beam computed tomography. Comput Methods Progr Biomed. 2017;146:91–100.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Ilhan B, Guneri P, Wilder-Smith P. The contribution of artificial intelligence to reducing the diagnostic delay in oral cancer. Oral Oncol. 2021;116: 105254.

Bouletreau P, Makaremi M, Ibrahim B, Louvrier A, Sigaux N. Artificial Intelligence: applications in orthognathic surgery. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019;120:347–54.

Gupta A, Kharbanda OP, Sardana V, Balachandran R, Sardana HK. Accuracy of 3D cephalometric measurements based on an automatic knowledge-based landmark detection algorithm. Int J CARS. 2016;11:1297–309.

Kunz F, Stellzig-Eisenhauer A, Zeman F, Boldt J. Artificial intelligence in orthodontics : evaluation of a fully automated cephalometric analysis using a customized convolutional neural network. J Orofac Orthop. 2020;81:52–68.

Kim H, Shim E, Park J, Kim YJ, Lee U, Kim Y. Web-based fully automated cephalometric analysis by deep learning. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2020;194:105513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2020.105513 .

Camci H, Salmanpour F. Estimating the size of unerupted teeth: Moyers vs. deep learning. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2022;161:451.