- How it works

"Christmas Offer"

Terms & conditions.

As the Christmas season is upon us, we find ourselves reflecting on the past year and those who we have helped to shape their future. It’s been quite a year for us all! The end of the year brings no greater joy than the opportunity to express to you Christmas greetings and good wishes.

At this special time of year, Research Prospect brings joyful discount of 10% on all its services. May your Christmas and New Year be filled with joy.

We are looking back with appreciation for your loyalty and looking forward to moving into the New Year together.

"Claim this offer"

In unfamiliar and hard times, we have stuck by you. This Christmas, Research Prospect brings you all the joy with exciting discount of 10% on all its services.

Offer valid till 5-1-2024

We love being your partner in success. We know you have been working hard lately, take a break this holiday season to spend time with your loved ones while we make sure you succeed in your academics

Discount code: RP0996Y

Use of Pronouns in Academic Writing

Published by Alvin Nicolas at August 17th, 2021 , Revised On August 24, 2023

Pronouns are words that make reference to both specific and nonspecific things and people. They are used in place of nouns.

First-person pronouns (I, We) are rarely used in academic writing. They are primarily used in a reflective piece, such as a reflective essay or personal statement. You should avoid using second-person pronouns such as “you” and “yours”. The use of third-person pronouns (He, She, They) is allowed, but it is still recommended to consider gender bias when using them in academic writing.

The antecedent of a pronoun is the noun that the pronoun represents. In English, you will see the antecedent appear both before and after the pronoun, even though it is usually mentioned in the text before the pronoun. The students could not complete the work on time because they procrastinated for too long. Before he devoured a big burger, Michael looked a bit nervous.

The Antecedent of a Pronoun

Make sure the antecedent is evident and explicit whenever you use a pronoun in a sentence. You may want to replace the pronoun with the noun to eliminate any vagueness.

- After the production and the car’s mechanical inspection were complete, it was delivered to the owner.

In the above sentence, it is unclear what the pronoun “it” is referring to.

- After the production and the car’s mechanical inspection was complete, the car was delivered to the owner.

Use of First Person Pronouns (I, We) in Academic Writing

The use of first-person pronouns, such as “I” and “We”, is a widely debated topic in academic writing.

While some style guides, such as ‘APA” and “Harvard”, encourage first-person pronouns when describing the author’s actions, many other style guides discourage their use in academic writing to keep the attention to the information presented within rather than who describes it.

Similarly, you will find some leniency towards the use of first-person pronouns in some academic disciplines, while others strictly prohibit using them to maintain an impartial and neutral tone.

It will be fair to say that first-person pronouns are increasingly regular in many forms of academic writing. If ever in doubt whether or not you should use first-person pronouns in your essay or assignment, speak with your tutor to be entirely sure.

Avoid overusing first-person pronouns in academic papers regardless of the style guide used. It is recommended to use them only where required for improving the clarity of the text.

If you are writing about a situation involving only yourself or if you are the sole author of the paper, then use the singular pronouns (I, my). Use plural pronouns (We, They, Our) when there are coauthors to work.

Avoiding First Person Pronouns

You can avoid first-person pronouns by employing any of the following three methods.

There are advantages and disadvantages of each of these three strategies. For example, passive voice introduces dangling modifiers, which can make your text unclear and ambiguous. Therefore, it would be best to keep first-person pronouns in the text if you can use them.

In some forms of academic writing, such as a personal statement and reflective essay, it is completely acceptable to use first-person pronouns.

The Problem with the Editorial We

Avoid using the first person plural to refer to people in academic text, known as the “editorial we”. The use of the “editorial we” is quite common in newspapers when the author speaks on behalf of the people to express a shared experience or view.

Refrain from using broad generalizations in academic text. You have to be crystal clear and very specific about who you are making reference to. Use nouns in place of pronouns where possible.

- When we tested the data, we found that the hypothesis to be incorrect.

- When the researchers tested the data, they found the hypothesis to be incorrect.

- As we started to work on the project, we realized how complex the requirements were.

- As the students started to work on the project, they realized how complex the requirements were.

If you are talking on behalf of a specific group you belong to, then the use of “we” is acceptable.

- It is essential to be aware of our own

- It is essential for essayists to be aware of their own weaknesses.

- Essayists need to be aware of their own

Use of Second Person Pronouns (You) in Academic Writing

It is strictly prohibited to use the second-person pronoun “you” to address the audience in any form of academic writing. You can rephrase the sentence or introduce the impersonal pronoun “one” to avoid second-person pronouns in the text.

- To achieve the highest academic grade, you must avoid procrastination.

- To achieve the highest academic grade, one must avoid procrastination.

- As you can notice in below Table 2.1, all participants selected the first option.

- As shown in below Table 2.1, all participants selected the first option.

Use of Third Person Pronouns (He, She, They) in Academic Writing

Third-person pronouns in the English language are usually gendered (She/Her, He/Him). Educational institutes worldwide are increasingly advocating for gender-neutral language, so you should avoid using third-person pronouns in academic text.

In the older academic text, you will see gender-based nouns (Fishermen, Traitor) and pronouns (him, her, he, she) being commonly used. However, this style of writing is outdated and warned against in the present times.

You may also see some authors using both masculine and feminine pronouns, such as “he” or “she”, in the same text, but this generally results in unclear and inappropriate sentences.

Considering using gender-neutral pronouns, such as “they”, ‘there”, “them” for unknown people and undetermined people. The use of “they” in academic writing is highly encouraged. Many style guides, including Harvard, MLA, and APA, now endorse gender natural pronouns in academic writing.

On the other hand, you can also choose to avoid using pronouns altogether by either revising the sentence structure or pluralizing the sentence’s subject.

- When a student is asked to write an essay, he can take a specific position on the topic.

- When a student is asked to write an essay, they can take a specific position on the topic.

- When students are asked to write an essay, they are expected to take a specific position on the topic.

- Students are expected to take a specific position on the essay topic.

- The writer submitted his work for approval

- The writer submitted their work for approval.

- The writers submitted their work for approval.

- The writers’ work was submitted for approval.

Make sure it is clear who you are referring to with the singular “they” pronoun. You may want to rewrite the sentence or name the subject directly if the pronoun makes the sentence ambiguous.

For example, in the following example, you can see it is unclear who the plural pronoun “they” is referring to. To avoid confusion, the subject is named directly, and the context approves that “their paper” addresses the writer.

- If the writer doesn’t complete the client’s paper in time, they will be frustrated.

- The client will be frustrated if the writer doesn’t complete their paper in due time.

If you need to make reference to a specific person, it would be better to address them using self-identified pronouns. For example, in the following sentence, you can see that each person is referred to using a different possessive pronoun.

The students described their experience with different academic projects: Mike talked about his essay, James talked about their poster presentation, and Sara talked about her dissertation paper.

Ensure Consistency Throughout the Text

Avoid switching back and forth between first-person pronouns (I, We, Our) and third-person pronouns (The writers, the students) in a single piece. It is vitally important to maintain consistency throughout the text.

For example, The writers completed the work in due time, and our content quality is well above the standard expected. We completed the work in due time, and our content quality is well above the standard expected. The writers completed the work in due time, and the content quality is well above the standard expected.“

How to Use Demonstrative Pronouns (This, That, Those, These) in Academic Writing

Make sure it is clear who you are referring to when using demonstrative pronouns. Consider placing a descriptive word or phrase after the demonstrative pronouns to give more clarity to the sentence.

For example, The political relationship between Israel and Arab states has continued to worsen over the last few decades, contrary to the expectations of enthusiasts in the regional political sphere. This shows that a lot more needs to be done to tackle this. The political relationship between Israel and Arab states has continued to worsen over the last few decades, contrary to the expectations of enthusiasts in the regional political sphere. This situation shows that a lot more needs to be done to tackle this issue.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the 8 types of pronouns.

The 8 types of pronouns are:

- Personal: Refers to specific persons.

- Demonstrative: Points to specific things.

- Interrogative: Used for questioning.

- Possessive: Shows ownership.

- Reflexive: Reflects the subject.

- Reciprocal: Indicates mutual action.

- Relative: Introduces relative clauses.

- Indefinite: Refers vaguely or generally.

You May Also Like

A modifier is a word that changes, clarifies, or limits a particular word in a sentence in order to add details, clarification, importance, or explanation.

We use prepositions to express relationships between different components of a sentence. This article explains the use of prepositions with examples.

The correct use of definite and indefinite articles can help you improve your essay or dissertation language. This guide explains the use of articles in writing with examples.

As Featured On

USEFUL LINKS

LEARNING RESOURCES

COMPANY DETAILS

Splash Sol LLC

- How It Works

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

Can You Use First-Person Pronouns (I/we) in a Research Paper?

Research writers frequently wonder whether the first person can be used in academic and scientific writing. In truth, for generations, we’ve been discouraged from using “I” and “we” in academic writing simply due to old habits. That’s right—there’s no reason why you can’t use these words! In fact, the academic community used first-person pronouns until the 1920s, when the third person and passive-voice constructions (that is, “boring” writing) were adopted–prominently expressed, for example, in Strunk and White’s classic writing manual “Elements of Style” first published in 1918, that advised writers to place themselves “in the background” and not draw attention to themselves.

In recent decades, however, changing attitudes about the first person in academic writing has led to a paradigm shift, and we have, however, we’ve shifted back to producing active and engaging prose that incorporates the first person.

Can You Use “I” in a Research Paper?

However, “I” and “we” still have some generally accepted pronoun rules writers should follow. For example, the first person is more likely used in the abstract , Introduction section , Discussion section , and Conclusion section of an academic paper while the third person and passive constructions are found in the Methods section and Results section .

In this article, we discuss when you should avoid personal pronouns and when they may enhance your writing.

It’s Okay to Use First-Person Pronouns to:

- clarify meaning by eliminating passive voice constructions;

- establish authority and credibility (e.g., assert ethos, the Aristotelian rhetorical term referring to the personal character);

- express interest in a subject matter (typically found in rapid correspondence);

- establish personal connections with readers, particularly regarding anecdotal or hypothetical situations (common in philosophy, religion, and similar fields, particularly to explore how certain concepts might impact personal life. Additionally, artistic disciplines may also encourage personal perspectives more than other subjects);

- to emphasize or distinguish your perspective while discussing existing literature; and

- to create a conversational tone (rare in academic writing).

The First Person Should Be Avoided When:

- doing so would remove objectivity and give the impression that results or observations are unique to your perspective;

- you wish to maintain an objective tone that would suggest your study minimized biases as best as possible; and

- expressing your thoughts generally (phrases like “I think” are unnecessary because any statement that isn’t cited should be yours).

Usage Examples

The following examples compare the impact of using and avoiding first-person pronouns.

Example 1 (First Person Preferred):

To understand the effects of global warming on coastal regions, changes in sea levels, storm surge occurrences and precipitation amounts were examined .

[Note: When a long phrase acts as the subject of a passive-voice construction, the sentence becomes difficult to digest. Additionally, since the author(s) conducted the research, it would be clearer to specifically mention them when discussing the focus of a project.]

We examined changes in sea levels, storm surge occurrences, and precipitation amounts to understand how global warming impacts coastal regions.

[Note: When describing the focus of a research project, authors often replace “we” with phrases such as “this study” or “this paper.” “We,” however, is acceptable in this context, including for scientific disciplines. In fact, papers published the vast majority of scientific journals these days use “we” to establish an active voice. Be careful when using “this study” or “this paper” with verbs that clearly couldn’t have performed the action. For example, “we attempt to demonstrate” works, but “the study attempts to demonstrate” does not; the study is not a person.]

Example 2 (First Person Discouraged):

From the various data points we have received , we observed that higher frequencies of runoffs from heavy rainfall have occurred in coastal regions where temperatures have increased by at least 0.9°C.

[Note: Introducing personal pronouns when discussing results raises questions regarding the reproducibility of a study. However, mathematics fields generally tolerate phrases such as “in X example, we see…”]

Coastal regions with temperature increases averaging more than 0.9°C experienced higher frequencies of runoffs from heavy rainfall.

[Note: We removed the passive voice and maintained objectivity and assertiveness by specifically identifying the cause-and-effect elements as the actor and recipient of the main action verb. Additionally, in this version, the results appear independent of any person’s perspective.]

Example 3 (First Person Preferred):

In contrast to the study by Jones et al. (2001), which suggests that milk consumption is safe for adults, the Miller study (2005) revealed the potential hazards of ingesting milk. The authors confirm this latter finding.

[Note: “Authors” in the last sentence above is unclear. Does the term refer to Jones et al., Miller, or the authors of the current paper?]

In contrast to the study by Jones et al. (2001), which suggests that milk consumption is safe for adults, the Miller study (2005) revealed the potential hazards of ingesting milk. We confirm this latter finding.

[Note: By using “we,” this sentence clarifies the actor and emphasizes the significance of the recent findings reported in this paper. Indeed, “I” and “we” are acceptable in most scientific fields to compare an author’s works with other researchers’ publications. The APA encourages using personal pronouns for this context. The social sciences broaden this scope to allow discussion of personal perspectives, irrespective of comparisons to other literature.]

Other Tips about Using Personal Pronouns

- Avoid starting a sentence with personal pronouns. The beginning of a sentence is a noticeable position that draws readers’ attention. Thus, using personal pronouns as the first one or two words of a sentence will draw unnecessary attention to them (unless, of course, that was your intent).

- Be careful how you define “we.” It should only refer to the authors and never the audience unless your intention is to write a conversational piece rather than a scholarly document! After all, the readers were not involved in analyzing or formulating the conclusions presented in your paper (although, we note that the point of your paper is to persuade readers to reach the same conclusions you did). While this is not a hard-and-fast rule, if you do want to use “we” to refer to a larger class of people, clearly define the term “we” in the sentence. For example, “As researchers, we frequently question…”

- First-person writing is becoming more acceptable under Modern English usage standards; however, the second-person pronoun “you” is still generally unacceptable because it is too casual for academic writing.

- Take all of the above notes with a grain of salt. That is, double-check your institution or target journal’s author guidelines . Some organizations may prohibit the use of personal pronouns.

- As an extra tip, before submission, you should always read through the most recent issues of a journal to get a better sense of the editors’ preferred writing styles and conventions.

Wordvice Resources

For more general advice on how to use active and passive voice in research papers, on how to paraphrase , or for a list of useful phrases for academic writing , head over to the Wordvice Academic Resources pages . And for more professional proofreading services , visit our Academic Editing and P aper Editing Services pages.

We Vs. They: Using the First & Third Person in Research Papers

Writing in the first , second , or third person is referred to as the author’s point of view . When we write, our tendency is to personalize the text by writing in the first person . That is, we use pronouns such as “I” and “we”. This is acceptable when writing personal information, a journal, or a book. However, it is not common in academic writing.

Some writers find the use of first , second , or third person point of view a bit confusing while writing research papers. Since second person is avoided while writing in academic or scientific papers, the main confusion remains within first or third person.

In the following sections, we will discuss the usage and examples of the first , second , and third person point of view.

First Person Pronouns

The first person point of view simply means that we use the pronouns that refer to ourselves in the text. These are as follows:

Can we use I or We In the Scientific Paper?

Using these, we present the information based on what “we” found. In science and mathematics, this point of view is rarely used. It is often considered to be somewhat self-serving and arrogant . It is important to remember that when writing your research results, the focus of the communication is the research and not the persons who conducted the research. When you want to persuade the reader, it is best to avoid personal pronouns in academic writing even when it is personal opinion from the authors of the study. In addition to sounding somewhat arrogant, the strength of your findings might be underestimated.

For example:

Based on my results, I concluded that A and B did not equal to C.

In this example, the entire meaning of the research could be misconstrued. The results discussed are not those of the author ; they are generated from the experiment. To refer to the results in this context is incorrect and should be avoided. To make it more appropriate, the above sentence can be revised as follows:

Based on the results of the assay, A and B did not equal to C.

Second Person Pronouns

The second person point of view uses pronouns that refer to the reader. These are as follows:

This point of view is usually used in the context of providing instructions or advice , such as in “how to” manuals or recipe books. The reason behind using the second person is to engage the reader.

You will want to buy a turkey that is large enough to feed your extended family. Before cooking it, you must wash it first thoroughly with cold water.

Although this is a good technique for giving instructions, it is not appropriate in academic or scientific writing.

Third Person Pronouns

The third person point of view uses both proper nouns, such as a person’s name, and pronouns that refer to individuals or groups (e.g., doctors, researchers) but not directly to the reader. The ones that refer to individuals are as follows:

- Hers (possessive form)

- His (possessive form)

- Its (possessive form)

- One’s (possessive form)

The third person point of view that refers to groups include the following:

- Their (possessive form)

- Theirs (plural possessive form)

Everyone at the convention was interested in what Dr. Johnson presented. The instructors decided that the students should help pay for lab supplies. The researchers determined that there was not enough sample material to conduct the assay.

The third person point of view is generally used in scientific papers but, at times, the format can be difficult. We use indefinite pronouns to refer back to the subject but must avoid using masculine or feminine terminology. For example:

A researcher must ensure that he has enough material for his experiment. The nurse must ensure that she has a large enough blood sample for her assay.

Many authors attempt to resolve this issue by using “he or she” or “him or her,” but this gets cumbersome and too many of these can distract the reader. For example:

A researcher must ensure that he or she has enough material for his or her experiment. The nurse must ensure that he or she has a large enough blood sample for his or her assay.

These issues can easily be resolved by making the subjects plural as follows:

Researchers must ensure that they have enough material for their experiment. Nurses must ensure that they have large enough blood samples for their assay.

Exceptions to the Rules

As mentioned earlier, the third person is generally used in scientific writing, but the rules are not quite as stringent anymore. It is now acceptable to use both the first and third person pronouns in some contexts, but this is still under controversy.

In a February 2011 blog on Eloquent Science , Professor David M. Schultz presented several opinions on whether the author viewpoints differed. However, there appeared to be no consensus. Some believed that the old rules should stand to avoid subjectivity, while others believed that if the facts were valid, it didn’t matter which point of view was used.

First or Third Person: What Do The Journals Say

In general, it is acceptable in to use the first person point of view in abstracts, introductions, discussions, and conclusions, in some journals. Even then, avoid using “I” in these sections. Instead, use “we” to refer to the group of researchers that were part of the study. The third person point of view is used for writing methods and results sections. Consistency is the key and switching from one point of view to another within sections of a manuscript can be distracting and is discouraged. It is best to always check your author guidelines for that particular journal. Once that is done, make sure your manuscript is free from the above-mentioned or any other grammatical error.

You are the only researcher involved in your thesis project. You want to avoid using the first person point of view throughout, but there are no other researchers on the project so the pronoun “we” would not be appropriate. What do you do and why? Please let us know your thoughts in the comments section below.

I am writing the history of an engineering company for which I worked. How do I relate a significant incident that involved me?

Hi Roger, Thank you for your question. If you are narrating the history for the company that you worked at, you would have to refer to it from an employee’s perspective (third person). If you are writing the history as an account of your experiences with the company (including the significant incident), you could refer to yourself as ”I” or ”My.” (first person) You could go through other articles related to language and grammar on Enago Academy’s website https://enago.com/academy/ to help you with your document drafting. Did you get a chance to install our free Mobile App? https://www.enago.com/academy/mobile-app/ . Make sure you subscribe to our weekly newsletter: https://www.enago.com/academy/subscribe-now/ .

Good day , i am writing a research paper and m y setting is a company . is it ethical to put the name of the company in the research paper . i the management has allowed me to conduct my research in thir company .

thanks docarlene diaz

Generally authors do not mention the names of the organization separately within the research paper. The name of the educational institution the researcher or the PhD student is working in needs to be mentioned along with the name in the list of authors. However, if the research has been carried out in a company, it might not be mandatory to mention the name after the name in the list of authors. You can check with the author guidelines of your target journal and if needed confirm with the editor of the journal. Also check with the mangement of the company whether they want the name of the company to be mentioned in the research paper.

Finishing up my dissertation the information is clear and concise.

How to write the right first person pronoun if there is a single researcher? Thanks

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

- Reporting Research

- Industry News

- Publishing Research

- AI in Academia

- Promoting Research

- Career Corner

- Diversity and Inclusion

- Infographics

- Expert Video Library

- Other Resources

- Enago Learn

- Upcoming & On-Demand Webinars

- Open Access Week 2024

- Peer Review Week 2024

- Conference Videos

- Enago Report

- Journal Finder

- Enago Plagiarism & AI Grammar Check

- Editing Services

- Publication Support Services

- Research Impact

- Translation Services

- Publication solutions

- AI-Based Solutions

- Thought Leadership

- Call for Articles

- Call for Speakers

- Author Training

- Edit Profile

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

Which among these would you prefer the most for improving research integrity?

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

Can You Use I or We in a Research Paper?

4-minute read

- 11th July 2023

Writing in the first person, or using I and we pronouns, has traditionally been frowned upon in academic writing . But despite this long-standing norm, writing in the first person isn’t actually prohibited. In fact, it’s becoming more acceptable – even in research papers.

If you’re wondering whether you can use I (or we ) in your research paper, you should check with your institution first and foremost. Many schools have rules regarding first-person use. If it’s up to you, though, we still recommend some guidelines. Check out our tips below!

When Is It Most Acceptable to Write in the First Person?

Certain sections of your paper are more conducive to writing in the first person. Typically, the first person makes sense in the abstract, introduction, discussion, and conclusion sections. You should still limit your use of I and we , though, or your essay may start to sound like a personal narrative .

Using first-person pronouns is most useful and acceptable in the following circumstances.

When doing so removes the passive voice and adds flow

Sometimes, writers have to bend over backward just to avoid using the first person, often producing clunky sentences and a lot of passive voice constructions. The first person can remedy this. For example:

Both sentences are fine, but the second one flows better and is easier to read.

When doing so differentiates between your research and other literature

When discussing literature from other researchers and authors, you might be comparing it with your own findings or hypotheses . Using the first person can help clarify that you are engaging in such a comparison. For example:

In the first sentence, using “the author” to avoid the first person creates ambiguity. The second sentence prevents misinterpretation.

When doing so allows you to express your interest in the subject

In some instances, you may need to provide background for why you’re researching your topic. This information may include your personal interest in or experience with the subject, both of which are easier to express using first-person pronouns. For example:

Expressing personal experiences and viewpoints isn’t always a good idea in research papers. When it’s appropriate to do so, though, just make sure you don’t overuse the first person.

When to Avoid Writing in the First Person

It’s usually a good idea to stick to the third person in the methods and results sections of your research paper. Additionally, be careful not to use the first person when:

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

● It makes your findings seem like personal observations rather than factual results.

● It removes objectivity and implies that the writing may be biased .

● It appears in phrases such as I think or I believe , which can weaken your writing.

Keeping Your Writing Formal and Objective

Using the first person while maintaining a formal tone can be tricky, but keeping a few tips in mind can help you strike a balance. The important thing is to make sure the tone isn’t too conversational.

To achieve this, avoid referring to the readers, such as with the second-person you . Use we and us only when referring to yourself and the other authors/researchers involved in the paper, not the audience.

It’s becoming more acceptable in the academic world to use first-person pronouns such as we and I in research papers. But make sure you check with your instructor or institution first because they may have strict rules regarding this practice.

If you do decide to use the first person, make sure you do so effectively by following the tips we’ve laid out in this guide. And once you’ve written a draft, send us a copy! Our expert proofreaders and editors will be happy to check your grammar, spelling, word choice, references, tone, and more. Submit a 500-word sample today!

Is it ever acceptable to use I or we in a research paper?

In some instances, using first-person pronouns can help you to establish credibility, add clarity, and make the writing easier to read.

How can I avoid using I in my writing?

Writing in the passive voice can help you to avoid using the first person.

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

5-minute read

Free Email Newsletter Template

Promoting a brand means sharing valuable insights to connect more deeply with your audience, and...

6-minute read

How to Write a Nonprofit Grant Proposal

If you’re seeking funding to support your charitable endeavors as a nonprofit organization, you’ll need...

9-minute read

How to Use Infographics to Boost Your Presentation

Is your content getting noticed? Capturing and maintaining an audience’s attention is a challenge when...

8-minute read

Why Interactive PDFs Are Better for Engagement

Are you looking to enhance engagement and captivate your audience through your professional documents? Interactive...

7-minute read

Seven Key Strategies for Voice Search Optimization

Voice search optimization is rapidly shaping the digital landscape, requiring content professionals to adapt their...

Five Creative Ways to Showcase Your Digital Portfolio

Are you a creative freelancer looking to make a lasting impression on potential clients or...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

Style Guide for Gender-Inclusive Writing

Photo by Sharon McCutcheon on Unsplash Article by Wendy Lee Spaček, Library Assistant for the Arts & Humanities Department, and Research Assistant for the Learning Commons at Wells Library. She is currently earning her Master in Library Science degree and in 2019 earned her MFA in Poetry from IU. She specializes in English, poetry, and teaching and learning. Her secondary interests include gender & sexuality studies and library conservation

Style Guides on the Singular Pronoun “They” & Gender-Inclusive Academic Writing

Academic style guides agree: honoring and using a person’s correct personal pronoun is a matter of respect, and it's good style.

All three major Academic Style Guides ( APA, the Chicago Manual of Style , and MLA ) agree that a person’s correct personal pronouns (they, he, she, etc.) should be respected and used at all times in formal and academic writing. It is not possible to infer a person’s pronouns just by looking at them. To determine the pronouns of someone you are writing about, refer to their biography, or if possible, ask them what personal pronouns they use. If their personal pronouns are unknown or cannot be determined, using singular “they” may be the solution if you are writing in APA or MLA. For those using Chicago, the guide recommends rewriting the text in a way that does not require using personal pronouns ( 5.256 ). Always take care in your writing to use the correct personal pronouns. Never assume a person’s pronouns when writing about them!

More about personal pronouns and how to use them

In English, personal pronouns are gendered. Historically, English offers only three personal pronouns: masculine (he), feminine (she), and the un-gendered “it” (which is widely seen as rude or disrespectful to use when referring to a person). These few personal pronouns do not adequately express the variety of gender expressions that have been present throughout history. Grammar is not static, but changes over time, adapting to, reflecting, and perpetuating biases and social constructs present in the culture. Many people have been excluded by this rigid and artificial binary representation of gender codified in the English language and have had to find or create alternatives to identify themselves in speech and writing.

Below is a chart that lists some of the most commonly used personal pronouns and gives examples for how to use them:

Academic Style Guides on the importance of achieving gender-neutral writing

Academic style guides agree on the importance of achieving gender-neutral writing, and the problem of using “he” as a universal pronoun. For a time, academic style guides suggested the use of “he or she” or alternating between “he” or “she” in writing. This construction is now acknowledged as being not only clunky and awkward, but exclusionary because to use “he or she” suggests a rigid gender binary, excluding all persons whose gender identities are outside of that binary. Luckily, singular “they,” in use since the 14th century in informal and spoken speech, has started to gain traction as a gender-inclusive pronoun to refer to a person of unknown gender in formal and academic writing. More on the history of singular “they” can be found at the Oxford English Dictionary’s website and Historians.org.

In 2021 Academic Style Guides are divided on the use of singular “they” as a gender-neutral unknown referent

Academic Style Guides adapt slowly to changes in grammar, and like grammar, are socially constructed texts that are constantly in flux. To understand Academic Style Guides’ current and past positions on singular “they” as a gender-neutral unknown referent, it is important to keep in mind that Academic Style Guides do not create grammatical rules. Rather, they establish formal guidelines that follow spoken and grammatical conventions which are set by informal writing and speech. Academic Style Guides are often slow to adopt conventions they might see as temporary. Despite the long history of singular “they” in this usage, which mirrors the grammatical evolution of singular “you,” some style guides have waffled on sanctioning its use.

As of 2021, all three major guides (APA, MLA, and Chicago) acknowledge the ubiquity of singular “they” for use with an unknown referent in informal writing and speech. However, only one of the three guides, the 7th Edition of APA’s Style Guide, fully endorses the use of singular “they” as “a generic third-person singular pronoun to refer to a person whose gender is unknown or irrelevant to the context of usage” (APA, 120). MLA, which leaves grammar largely up to the discretion of the author, neither endorses nor prohibits the use of singular “they” in this sense. As a result, it is acceptable in MLA Style. The Chicago Manual of Style (CMOS) has a particularly complicated history with singular “they” as a gender-neutral unknown referent. In the 1993 edition, it endorsed “they/their” in this sense (Chicago, 13th Ed. 2.98). However, this was removed from subsequent editions. Though CMOS acknowledges the ubiquity of this usage, it continues to prohibit its use and instead recommends rewriting the sentence in some way that eliminates the need for a pronoun. For more on the history of singular “they” and the Chicago Manual of Style, take a look at this 2017 article written by Cai Fischietto on IU Libraries’ website.

Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association: The Official Guide to APA Style. Seventh edition, American Psychological Association, 2020.

MLA Handbook. Eighth edition, The Modern Language Association of America, 2016.

The Chicago Manual of Style. Seventeenth edition, The University of Chicago Press, 2017.

The Chicago Manual of Style. Thirteenth edition, The University of Chicago Press, 1993, pp. 76-77.

Further reading on gender-inclusive writing

Trans Journalists Association's Style Guide

Further reading on the singular pronoun “they”

Merriam-Webster's Words at Play blog on the evolution of singular "they"

Singular "they" is Merriam Webster's 2020 word of the year

Singular "they" is the American Dialect Society's Word of the Decade

IU Libraries 2016 article Academic Style Guides on the Singular Pronoun 'They' by Cai Fischietto

Style Guides on singular “they”

The Chicago Manual of Style, 17th Edition, 5.48

American Psychological Association (APA) Style Guide

Modern Language Association (MLA) Style Guide

Further Reading

2019 Guardian article about the development of gender-neutral writing around the world

Social media

Additional resources, featured databases.

- OneSearch@IU

- Google Scholar

- HathiTrust Digital Library

IU Libraries

- Reservable Spaces

- Our Departments

- Intranet SharePoint (Staff)

- Website Login (Staff)

Should I Use “I”?

What this handout is about.

This handout is about determining when to use first person pronouns (“I”, “we,” “me,” “us,” “my,” and “our”) and personal experience in academic writing. “First person” and “personal experience” might sound like two ways of saying the same thing, but first person and personal experience can work in very different ways in your writing. You might choose to use “I” but not make any reference to your individual experiences in a particular paper. Or you might include a brief description of an experience that could help illustrate a point you’re making without ever using the word “I.” So whether or not you should use first person and personal experience are really two separate questions, both of which this handout addresses. It also offers some alternatives if you decide that either “I” or personal experience isn’t appropriate for your project. If you’ve decided that you do want to use one of them, this handout offers some ideas about how to do so effectively, because in many cases using one or the other might strengthen your writing.

Expectations about academic writing

Students often arrive at college with strict lists of writing rules in mind. Often these are rather strict lists of absolutes, including rules both stated and unstated:

- Each essay should have exactly five paragraphs.

- Don’t begin a sentence with “and” or “because.”

- Never include personal opinion.

- Never use “I” in essays.

We get these ideas primarily from teachers and other students. Often these ideas are derived from good advice but have been turned into unnecessarily strict rules in our minds. The problem is that overly strict rules about writing can prevent us, as writers, from being flexible enough to learn to adapt to the writing styles of different fields, ranging from the sciences to the humanities, and different kinds of writing projects, ranging from reviews to research.

So when it suits your purpose as a scholar, you will probably need to break some of the old rules, particularly the rules that prohibit first person pronouns and personal experience. Although there are certainly some instructors who think that these rules should be followed (so it is a good idea to ask directly), many instructors in all kinds of fields are finding reason to depart from these rules. Avoiding “I” can lead to awkwardness and vagueness, whereas using it in your writing can improve style and clarity. Using personal experience, when relevant, can add concreteness and even authority to writing that might otherwise be vague and impersonal. Because college writing situations vary widely in terms of stylistic conventions, tone, audience, and purpose, the trick is deciphering the conventions of your writing context and determining how your purpose and audience affect the way you write. The rest of this handout is devoted to strategies for figuring out when to use “I” and personal experience.

Effective uses of “I”:

In many cases, using the first person pronoun can improve your writing, by offering the following benefits:

- Assertiveness: In some cases you might wish to emphasize agency (who is doing what), as for instance if you need to point out how valuable your particular project is to an academic discipline or to claim your unique perspective or argument.

- Clarity: Because trying to avoid the first person can lead to awkward constructions and vagueness, using the first person can improve your writing style.

- Positioning yourself in the essay: In some projects, you need to explain how your research or ideas build on or depart from the work of others, in which case you’ll need to say “I,” “we,” “my,” or “our”; if you wish to claim some kind of authority on the topic, first person may help you do so.

Deciding whether “I” will help your style

Here is an example of how using the first person can make the writing clearer and more assertive:

Original example:

In studying American popular culture of the 1980s, the question of to what degree materialism was a major characteristic of the cultural milieu was explored.

Better example using first person:

In our study of American popular culture of the 1980s, we explored the degree to which materialism characterized the cultural milieu.

The original example sounds less emphatic and direct than the revised version; using “I” allows the writers to avoid the convoluted construction of the original and clarifies who did what.

Here is an example in which alternatives to the first person would be more appropriate:

As I observed the communication styles of first-year Carolina women, I noticed frequent use of non-verbal cues.

Better example:

A study of the communication styles of first-year Carolina women revealed frequent use of non-verbal cues.

In the original example, using the first person grounds the experience heavily in the writer’s subjective, individual perspective, but the writer’s purpose is to describe a phenomenon that is in fact objective or independent of that perspective. Avoiding the first person here creates the desired impression of an observed phenomenon that could be reproduced and also creates a stronger, clearer statement.

Here’s another example in which an alternative to first person works better:

As I was reading this study of medieval village life, I noticed that social class tended to be clearly defined.

This study of medieval village life reveals that social class tended to be clearly defined.

Although you may run across instructors who find the casual style of the original example refreshing, they are probably rare. The revised version sounds more academic and renders the statement more assertive and direct.

Here’s a final example:

I think that Aristotle’s ethical arguments are logical and readily applicable to contemporary cases, or at least it seems that way to me.

Better example

Aristotle’s ethical arguments are logical and readily applicable to contemporary cases.

In this example, there is no real need to announce that that statement about Aristotle is your thought; this is your paper, so readers will assume that the ideas in it are yours.

Determining whether to use “I” according to the conventions of the academic field

Which fields allow “I”?

The rules for this are changing, so it’s always best to ask your instructor if you’re not sure about using first person. But here are some general guidelines.

Sciences: In the past, scientific writers avoided the use of “I” because scientists often view the first person as interfering with the impression of objectivity and impersonality they are seeking to create. But conventions seem to be changing in some cases—for instance, when a scientific writer is describing a project she is working on or positioning that project within the existing research on the topic. Check with your science instructor to find out whether it’s o.k. to use “I” in their class.

Social Sciences: Some social scientists try to avoid “I” for the same reasons that other scientists do. But first person is becoming more commonly accepted, especially when the writer is describing their project or perspective.

Humanities: Ask your instructor whether you should use “I.” The purpose of writing in the humanities is generally to offer your own analysis of language, ideas, or a work of art. Writers in these fields tend to value assertiveness and to emphasize agency (who’s doing what), so the first person is often—but not always—appropriate. Sometimes writers use the first person in a less effective way, preceding an assertion with “I think,” “I feel,” or “I believe” as if such a phrase could replace a real defense of an argument. While your audience is generally interested in your perspective in the humanities fields, readers do expect you to fully argue, support, and illustrate your assertions. Personal belief or opinion is generally not sufficient in itself; you will need evidence of some kind to convince your reader.

Other writing situations: If you’re writing a speech, use of the first and even the second person (“you”) is generally encouraged because these personal pronouns can create a desirable sense of connection between speaker and listener and can contribute to the sense that the speaker is sincere and involved in the issue. If you’re writing a resume, though, avoid the first person; describe your experience, education, and skills without using a personal pronoun (for example, under “Experience” you might write “Volunteered as a peer counselor”).

A note on the second person “you”:

In situations where your intention is to sound conversational and friendly because it suits your purpose, as it does in this handout intended to offer helpful advice, or in a letter or speech, “you” might help to create just the sense of familiarity you’re after. But in most academic writing situations, “you” sounds overly conversational, as for instance in a claim like “when you read the poem ‘The Wasteland,’ you feel a sense of emptiness.” In this case, the “you” sounds overly conversational. The statement would read better as “The poem ‘The Wasteland’ creates a sense of emptiness.” Academic writers almost always use alternatives to the second person pronoun, such as “one,” “the reader,” or “people.”

Personal experience in academic writing

The question of whether personal experience has a place in academic writing depends on context and purpose. In papers that seek to analyze an objective principle or data as in science papers, or in papers for a field that explicitly tries to minimize the effect of the researcher’s presence such as anthropology, personal experience would probably distract from your purpose. But sometimes you might need to explicitly situate your position as researcher in relation to your subject of study. Or if your purpose is to present your individual response to a work of art, to offer examples of how an idea or theory might apply to life, or to use experience as evidence or a demonstration of an abstract principle, personal experience might have a legitimate role to play in your academic writing. Using personal experience effectively usually means keeping it in the service of your argument, as opposed to letting it become an end in itself or take over the paper.

It’s also usually best to keep your real or hypothetical stories brief, but they can strengthen arguments in need of concrete illustrations or even just a little more vitality.

Here are some examples of effective ways to incorporate personal experience in academic writing:

- Anecdotes: In some cases, brief examples of experiences you’ve had or witnessed may serve as useful illustrations of a point you’re arguing or a theory you’re evaluating. For instance, in philosophical arguments, writers often use a real or hypothetical situation to illustrate abstract ideas and principles.

- References to your own experience can explain your interest in an issue or even help to establish your authority on a topic.

- Some specific writing situations, such as application essays, explicitly call for discussion of personal experience.

Here are some suggestions about including personal experience in writing for specific fields:

Philosophy: In philosophical writing, your purpose is generally to reconstruct or evaluate an existing argument, and/or to generate your own. Sometimes, doing this effectively may involve offering a hypothetical example or an illustration. In these cases, you might find that inventing or recounting a scenario that you’ve experienced or witnessed could help demonstrate your point. Personal experience can play a very useful role in your philosophy papers, as long as you always explain to the reader how the experience is related to your argument. (See our handout on writing in philosophy for more information.)

Religion: Religion courses might seem like a place where personal experience would be welcomed. But most religion courses take a cultural, historical, or textual approach, and these generally require objectivity and impersonality. So although you probably have very strong beliefs or powerful experiences in this area that might motivate your interest in the field, they shouldn’t supplant scholarly analysis. But ask your instructor, as it is possible that they are interested in your personal experiences with religion, especially in less formal assignments such as response papers. (See our handout on writing in religious studies for more information.)

Literature, Music, Fine Arts, and Film: Writing projects in these fields can sometimes benefit from the inclusion of personal experience, as long as it isn’t tangential. For instance, your annoyance over your roommate’s habits might not add much to an analysis of “Citizen Kane.” However, if you’re writing about Ridley Scott’s treatment of relationships between women in the movie “Thelma and Louise,” some reference your own observations about these relationships might be relevant if it adds to your analysis of the film. Personal experience can be especially appropriate in a response paper, or in any kind of assignment that asks about your experience of the work as a reader or viewer. Some film and literature scholars are interested in how a film or literary text is received by different audiences, so a discussion of how a particular viewer or reader experiences or identifies with the piece would probably be appropriate. (See our handouts on writing about fiction , art history , and drama for more information.)

Women’s Studies: Women’s Studies classes tend to be taught from a feminist perspective, a perspective which is generally interested in the ways in which individuals experience gender roles. So personal experience can often serve as evidence for your analytical and argumentative papers in this field. This field is also one in which you might be asked to keep a journal, a kind of writing that requires you to apply theoretical concepts to your experiences.

History: If you’re analyzing a historical period or issue, personal experience is less likely to advance your purpose of objectivity. However, some kinds of historical scholarship do involve the exploration of personal histories. So although you might not be referencing your own experience, you might very well be discussing other people’s experiences as illustrations of their historical contexts. (See our handout on writing in history for more information.)

Sciences: Because the primary purpose is to study data and fixed principles in an objective way, personal experience is less likely to have a place in this kind of writing. Often, as in a lab report, your goal is to describe observations in such a way that a reader could duplicate the experiment, so the less extra information, the better. Of course, if you’re working in the social sciences, case studies—accounts of the personal experiences of other people—are a crucial part of your scholarship. (See our handout on writing in the sciences for more information.)

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Welcome to the new OASIS website! We have academic skills, library skills, math and statistics support, and writing resources all together in one new home.

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Scholarly Voice: First-Person Point of View

First-person point of view.

Since 2007, Walden academic leadership has endorsed the APA manual guidance on appropriate use of the first-person singular pronoun "I," allowing the use of this pronoun in all Walden academic writing except doctoral capstone abstracts, which should not contain first person pronouns.

In addition to the pointers below, APA 7, Section 4.16 provides information on the appropriate use of first person in scholarly writing.

Inappropriate Uses: I feel that eating white bread causes cancer. The author feels that eating white bread causes cancer. I found several sources (Marks, 2011; Isaac, 2006; Stuart, in press) that showed a link between white bread consumption and cancer. Appropriate Use: I surveyed 2,900 adults who consumed white bread regularly. In this chapter, I present a literature review on research about how seasonal light changes affect depression.

Confusing Sentence: The researcher found that the authors had been accurate in their study of helium, which the researcher had hypothesized from the beginning of their project. Revision: I found that Johnson et al. (2011) had been accurate in their study of helium, which I had hypothesized since I began my project.

Passive voice: The surveys were distributed and the results were compiled after they were collected. Revision: I distributed the surveys, and then I collected and compiled the results.

Appropriate use of first person we and our : Two other nurses and I worked together to create a qualitative survey to measure patient satisfaction. Upon completion, we presented the results to our supervisor.

Make assumptions about your readers by putting them in a group to which they may not belong by using first person plural pronouns. Inappropriate use of first person "we" and "our":

- We can stop obesity in our society by changing our lifestyles.

- We need to help our patients recover faster.

In the first sentence above, the readers would not necessarily know who "we" are, and using a phrase such as "our society " can immediately exclude readers from outside your social group. In the second sentence, the author assumes that the reader is a nurse or medical professional, which may not be the case, and the sentence expresses the opinion of the author.

To write with more precision and clarity, hallmarks of scholarly writing, revise these sentences without the use of "we" and "our."

- Moderate activity can reduce the risk of obesity (Hu et al., 2003).

- Staff members in the health care industry can help improve the recovery rate for patients (Matthews, 2013).

Pronouns Video

- APA Formatting & Style: Pronouns (video transcript)

Related Resources

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Previous Page: Point of View

- Next Page: Second-Person Point of View

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Cost of Attendance

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Appropriate Pronoun Usage

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Because English has no generic singular—or common-sex—pronoun, we have used HE, HIS, and HIM in such expressions as "the student needs HIS pencil." When we constantly personify "the judge," "the critic," "the executive," "the author," and so forth, as male by using the pronoun HE, we are subtly conditioning ourselves against the idea of a female judge, critic, executive, or author. There are several alternative approaches for ending the exclusion of women that results from the pervasive use of masculine pronouns.

Recast into the plural

- Original: Give each student his paper as soon as he is finished.

- Alternative: Give students their papers as soon as they are finished.

Reword to eliminate gender problems.

- Original: The average student is worried about his grade.

- Alternative: The average student is worried about grades.

Replace the masculine pronoun with ONE, YOU, or (sparingly) HE OR SHE, as appropriate.

- Original: If the student was satisfied with his performance on the pretest, he took the post-test.

- Alternative: A student who was satisfied with her or his performance on the pretest took the post-test.

Alternate male and female examples and expressions. (Be careful not to confuse the reader.)

- Original: Let each student participate. Has he had a chance to talk? Could he feel left out?

- Alternative: Let each student participate. Has she had a chance to talk? Could he feel left out?

Indefinite Pronouns

Using the masculine pronouns to refer to an indefinite pronoun ( everybody, everyone, anybody, anyone ) also has the effect of excluding women. In all but strictly formal uses, plural pronouns have become acceptable substitutes for the masculine singular.

- Original: Anyone who wants to go to the game should bring his money tomorrow.

- Alternative: Anyone who wants to go to the game should bring their money tomorrow.

An alternative to this is merely changing the sentence. English is very flexible, so there is little reason to "write yourself into a corner":

- Original: Anyone who wants to go to the game should bring his money.

- Alternative: People who want to go to the game should bring their money.

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

I understand you feel that way, but I feel this way: the benefits of I-language and communicating perspective during conflict

Shane l rogers, jill howieson, casey neame.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Corresponding author.

Received 2018 Feb 23; Accepted 2018 May 3; Collection date 2018.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

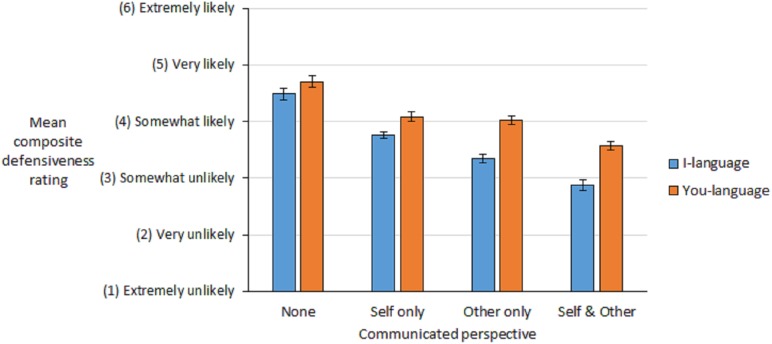

Using hypothetical scenarios, we provided participants with potential opening statements to a conflict discussion that varied on I/you language and communicated perspective. Participants rated the likelihood that the recipient of the statement would react in a defensive manner. Using I-language and communicating perspective were both found to reduce perceptions of hostility. Statements that communicated both self- and other-perspective using I-language (e.g. ‘I understand why you might feel that way, but I feel this way, so I think the situation is unfair’ ) were rated as the best strategy to open a conflict discussion. Simple acts of initial language use can reduce the chances that conflict discussion will descend into a downward spiral of hostility.

Keywords: Communicating perspective, I-statements, You-statements, Defensiveness, Hostility, Interpersonal conflict, Hypothetical scenarios, Factorial ANOVA, Perspective taking, Rating statements

Introduction

During interpersonal conflict, the initial communication style can set the scene for the remainder of the discussion ( Drake & Donohue, 1996 ). A psychological principle termed the norm of reciprocity describes a basic human tendency to match the behaviour and communication style of one’s partner during social interaction ( Park & Antonioni, 2007 ). During conflict, a hostile approach typically produces hostility in return from the other person, potentially creating a negative downward spiral ( Bowen, Winczewski & Collins, 2016 ; Park & Antonioni, 2007 ; Pike & Sillars, 1985 ; Wiebe & Zhang, 2017 ). Therefore, it is not surprising that recommendations abound in the academic and popular literature about specific communication tactics to minimise perceptions of hostility ( Bloomquist, 2012 ; Hargie, 2011 ; Heydenberk & Heydenberk, 2007 ; Howieson & Priddis, 2015 ; Kidder, 2017 ; Moore, 2014 ; Whitcomb & Whitcomb, 2013 ).

The present research assesses two specific aspects of language style that theorists have recommended as beneficial tactics for minimising hostility during conflict: the use of I-language instead of you-language, and communicating perspective ( Hargie, 2011 ). We broadly define communicating perspective as language that is clearly communicating one’s own point of view, and/or communicating an understanding of the perspective of the other person. This paper sets out to examine the relative merits of I-language and communicating perspective, both singularly, and used together, to open communication to prevent conflict escalation.

Communicating perspective—giving and taking

Consideration of the perspective of the other party is widely held to be beneficial during conflict ( Ames, 2008 ; Galinksy et al., 2008 ; Hargie, 2011 ; Howieson & Priddis, 2015 ; Kidder, 2017 ). An understanding of perspectives facilitates a more integrative approach where parties are willing to compromise to arrive at a mutually beneficial solution ( Galinksy et al., 2008 ; Kemp & Smith, 1994 ; Todd & Galinsky, 2014 ). Therefore, in dispute resolution a mediator will endeavour to encourage perspective taking by both parties ( Howieson & Priddis, 2012 , 2015 ; Ingerson, DeTienne & Liljenquist, 2015 ; Kidder, 2017 ; Lee et al., 2015 ). However, fostering perspective taking is more involved than simply telling someone to try and consider the other person’s point of view. In the negotiation/mediation literature it is recognised that increasing levels of perspective taking is best achieved via the communication process that occurs during a negotiation ( Howieson & Priddis, 2012 , 2015 ; Kidder, 2017 ).

It is important to consider that perspective taking is an internal cognitive process, so is not readily apparent to the other party unless it is made observable via communication ( Kellas, Willer & Trees, 2013 ). Kellas, Willer & Trees (2013) refer to this as communicating perspective taking , and report that married couples typically perceive agreement, relevant contributions, coordination, and positive tone as communicated evidence of perspective taking. A more direct strategy to communicate perspective taking is to paraphrase the perspective of the other party ( Howieson & Priddis, 2015 ; Kidder, 2017 ). For example, by explicitly stating what you perceive is the other’s point of view by saying something like ‘What I’m hearing is that perhaps you aren’t seeing enough evidence of appreciation and so feel like you’re being taken for granted’. Seehausen et al. (2012) demonstrated the utility of paraphrasing by interviewing participants (interviewees) about a recent social conflict while varying interviewer responses across participants as simple note taking or paraphrasing. Interviewees receiving paraphrase responses reported feeling less negative emotion associated with the conflict compared to interviewees receiving note taking responses. Similarly, other research has reported that perceptions of empathic effort during conflict is associated with relationship satisfaction ( Cohen et al., 2012 ).

While communicating perspective taking is useful during conflict, so is perspective giving (i.e. attempting to communicate one’s own position/perspective) ( Bruneau & Saxe, 2012 ; Graumann, 1989 ). For example, ‘I am not feeling great about this because I don’t feel like I am receiving a fair deal’. Perspective giving can be beneficial for the person offering the perspective to help them ‘feel heard’ ( Bruneau & Saxe, 2012 ), and also assist the other party to engage in perspective taking, which fosters a greater sense of mutual understanding ( Ames, 2008 ; Ames & Wazlawek, 2014 ). This is why negotiation experts recommend that during conflict both parties should communicate what their perspective is, and also communicate explicitly to the other person that they are attempting to consider their perspective ( Howieson & Priddis, 2015 ). However, while communication of perspective taking and giving have received research attention individually, no prior research has attempted to systematically compare them. In the present study we examine the perception of statements that vary in the extent of communicated perspective (i.e. none, self-only, other-only, self & other). By contrasting two types of communicating perspective (i.e. giving and taking) we can contribute to the research literature while also answering questions that have practical relevance for everyday communication.

I-Language and You-Language

Another aspect of language that is beneficial during conflict is the use of I-language (e.g. ‘I think things need to change’ ) versus you-language (e.g. ‘You need to change’ ) ( Hargie, 2011 ; Kubany et al., 1992a ; Simmons, Gordon & Chambless, 2005 ). For example, Simmons, Gordon & Chambless (2005) reported that a higher proportion of I-language and a lower proportion of you-language was associated with better problem solving and higher marital satisfaction. Similarly, Bieson, Schooler & Smith (2016) found that more frequent you-language during face-to-face conflict discussion was negatively associated with interaction quality of couples.

Kubany and colleagues took an experimental approach to directly assess the impact of I/you-language by examining participant ratings for statements that varied inclusion of I-language or you-language. Their research focused on the communication of emotion using I-statements (e.g. ‘I am feeling upset’ ) versus you-statements (e.g. ‘You have made me upset’ ). In a series of studies it was found that I-language was less likely to evoke negative emotions and more likely to evoke compassion and cooperative behavioural inclinations in the recipient ( Kubany et al., 1992b , 1995a , 1995b ). The benefit of I-language over you-language is that I-language communicates to the recipient that the sender acknowledges they are communicating from their own point of view and therefore they are open to negotiation ( Burr, 1990 ). Further, recipients often perceive you-language as accusatory and hostile ( Burr, 1990 ; Hargie, 2011 ; Kubany et al., 1992a ).

Furthermore, research from the embodied cognition field of study has produced evidence to suggest that text narratives using you-language foster more self-referential processing in the reader compared to I-language ( Beveridge & Pickering, 2013 ; Brunye et al., 2009 , 2011 ; Ditman et al., 2010 ). Compared to I-language, studies have found you-language associated with subsequent faster response times for pictures from a self-perspective (versus other-perspective) ( Brunye et al., 2009 ), better memory performance ( Ditman et al., 2010 ), and higher emotional reactivity ( Brunye et al., 2011 ). While these studies do not directly investigate conflict, the finding that you-language fosters greater self-referential processing is of relevance for conflict. As previously mentioned, during conflict the ideal scenario is for both parties to engage in mutual perspective taking to facilitate the search for a mutually beneficial solution. Therefore, you-language has potential to foster inward focus that can reduce the amount of perspective taking during communication.

The present study

The present study will extend earlier research investigating the impact of I/you language and communicated perspective by employing a rating statements design similar to the experimental research of Kubany and colleagues ( Kubany et al., 1992a , 1992b , 1995a , 1995b ). Based on prior research, we hypothesise that participants will rate: (1) I-language as less likely to provoke a defensive reaction than you-language ( Kubany et al., 1992a , 1992b ; Simmons, Gordon & Chambless, 2005 ); and (2) communicating perspective as less likely to provoke a defensive reaction compared to statements that do not communicate any clear perspective ( Cohen et al., 2012 ; Gordon & Chen, 2016 ; Howieson & Priddis, 2015 ; Kellas, Willer & Trees, 2013 ).

Importantly, we also varied the type of communicated perspective. As there has not been any prior research contrasting self-oriented versus other-oriented communicated perspective using a statement-rating paradigm, only tentative expectations were possible. We anticipated that a blend of one’s own and the other’s perspective would be received the best. We think this strategy is superior because it conveys both understanding (by acknowledging the other) and positive assertion (by acknowledging the self) ( Howieson & Priddis, 2015 ).

Participants

Participants were 253 university students (Mean = 28 years; SD = 8.75; 77% female). Prior to commencement of the research ethical approval was obtained from Edith Cowan University ethics committee (Ref: 15257). All participants supplied informed consent to take part in this research. Prior research by Kubany and colleagues using a similar rating statements paradigm reported significant effects with relatively low sample sizes ranging from 16 to 40 ( Kubany et al., 1992a , 1992b , 1995a ), with one study using a larger sample of 160 ( Kubany et al., 1995b ). We were therefore initially aiming to collect around 100 responses, but ended up with a larger sample, which has the benefit of assisting us feel more confident in our results.

Six hypothetical scenarios were constructed that described a hypothetical conflict situation. One example scenario was: Mike and his partner Lucy are living together and both working full time. Whenever Mike does some cleaning of the house and asks Lucy to help, Lucy typically replies that she is too tired after a full day at work to do cleaning. Mike feels it is unfair that he should be responsible for all the cleaning duties .

Each scenario was designed with two protagonists, an offended party (e.g. Mike), and the party causing offense (e.g. Lucy). An overall problem was communicated within the scenario description (e.g. Lucy is not helping to clean the house as often as Mike would like). In addition, both the perspective of the offended party (e.g. Mike feels it unfair that he is responsible for all cleaning), and the offending party (e.g. Lucy is usually very tired after a full day at her work) were also included. After reading a scenario, the participant was presented with eight statements that the offended party might use to begin a conflict discussion with the offending party. These statements varied on the usage of I/you language and communicated perspective. Table 1 shows all the statements presented to participants for the example scenario.

Table 1. Example statements provided to participants.