An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Nurses’ Time Allocation and Multitasking of Nursing Activities: A Time Motion Study

Po-yin yen , phd, rn, marjorie kellye , ms, rn, marcelo lopetegui , ms, md, abhijoy saha , ms, jacqueline loversidge , phd, rn, esther m chipps , phd, rn, lynn gallagher-ford , phd, rn, faan, jacalyn buck , phd, rn.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Collection date 2018.

This is an Open Access article: verbatim copying and redistribution of this article are permitted in all media for any purpose

Nurses have been required to provide more patient-centered, efficient, and cost effective care. In order to do so, they need to work at the top of their license. We conducted a time motion study to document nursing activities on communication, hands-on tasks, and locations (where activities occurred), and compared differences between different time blocks (7am-11am, 11am-3pm, and 3pm-7pm). We found that nurses spent most of their time communicating with patients and in patient rooms. Nurses also spent most of their time charting and reviewing information in EHR, mostly at the nursing station. Nurses’ work was not distributed equally across a 12-hour shift. We found that greater frequency and duration in hands-on tasks occurred between 7am-11am. In addition, nurses spent approximately 10% of their time on delegable and non-nursing activities, which could be used more effectively for patient care. The study results provide evidence to assist nursing leaders to develop strategies for transforming nursing practice through re-examination of nursing work and activities, and to promote nurses working at top of license for high quality care and best outcomes. Our research also presents a novel and quantifiable method to capture data on multidimensional levels of nursing activities.

Introduction

Besides producing high quality patient outcomes, nursing care has been required to be more patient-centered, efficient, and cost effective. However, research suggests that nurses spend a considerable amount of non-value added time on activities that could potentially be delegated to other team members with greater cost effectiveness. 1 Inefficiencies also contribute to non-value added time. 1 - 3 Within the past 10 years, Health Information Technology (IT) has had a major impact on health systems. Electronic health records (EHR) system adoption rose from 10% (2008) to 80% (2015) in the United States because of national regulation and incentives. 4 - 6 In addition, mobile devices, smart infusion pumps, barcode medication administration systems (BCMA), electronic whiteboards, and numerous technologies have been implemented or are pending implementation in hospitals. Health IT influences patient care, nursing activities, and turnover time and volume. 7 However, study results are mixed when evaluating the effect of EHR implementation on care and documentation times. Several studies reported an increase in patient care time due to decreased administrative task time and documentation time after implementing the electronic documentation system. 8 , 9 Others reported increased documentation time. 7 , 10 How these findings could support nurses’ work remains unclear.

Working within the complex healthcare environment of today, nurses must provide care that is efficient and effective. There is a growing body of literature describing nurses’ work using observational studies. 11 - 19 Some of this research have been conducted using electronic devices, such as a Personal Digital Assistant (PDA), 20 , 21 while others have utilized a stopwatch and paper/pencil. Observation accuracy could be limited because of the time necessary for paper/pencil documentation. While these studies reported a wide range of observation timeframe (e.g. 5am-5pm), none reported the distribution of the time period observed. 20 - 24 As a result, it is unclear whether the data were skewed to certain hours that observations were easier to schedule, if the observation was taken during the full shift length (8-12 hours), or whether observation fatigue was taken into account for quality control. Also, although task definitions were provided in most studies, it is unclear whether the start time and the end time of each activity was controlled, thus limiting the replication of the study. Other methodological limitations include randomly selected observation periods of 1-3 hours, 20 , 25 , 26 self-monitoring time motion study, 27 manual paper-based & stopwatch data collection, 22 confounding variables (e.g. nurse-patient ratio and patient acuity level 28 - 30 ) not observed or controlled, and focusing on single nursing activity (e.g. documentation, 7 , 9 medication administration, 31 - 33 communication, 34 glycemic control 26 ). These limitations prevent study replication and generalizability of study findings.

Multitasking is the nature of nurses’ work. To understand multitasking, examining the context of patient care is essiential. 35 Measuring multitasking enables healthcare organizations to improve efficiency, quality and safety, workflow, and clinician job satisfaction. 36 The concept of multitasking is often confused with task switching, which involves frequent and rapid changes between two tasks. 37 Various methods have been used to understand multitasking. However, reliability, accuracy, or generalizability of these studies 20 , 36 , 38 - 40 were compromised due to limited approaches or technology (e.g. manual recording process, 38 , 39 poorly designed electronic data collection device. 20 , 21 , 41 )

The work of nursing also involves interruptions. While some interruptions may be necessary for positive patient outcomes, 42 most are not. 43 , 44 A study reported that nurses were most likely to be interrupted and to multitask during medication administration. 21 Such overrepresentation of multitasking behavior during medication administration raises patient safety issues. Medication interruptions have been widely reported to be associated with medication errors 45 , 46 and can pose life-threatening consequences for patients. 43 , 44 , 47 Research is needed to accurately capture interruptions as they relate to multitasking behaviors and how these behaviors contribute to nuring errors.

We conducted a time motion study to observe and record nursing activities during their working day shifts between 7am to 7pm. In a prior publication, we reported our time motion study design and approaches to collect and visualize nursing workflow in three activity dimensions: communication, task and location. 48 Communication represents whom nurses are interacting with; hands-on tasks represent tasks nurses are physically performing (i.e. preparing medication); and location represents where nursing activities take place. We operationalized our definition of multitasking as the observable performance of two or more tasks simultaneously, 49 for example, talking to a patient and preparing medication. We explored these three activity dimensions, across the continuum of time to understand multitasking and task switching in nursing practice. 48 We also controlled the distribution of observation time by splitting the 12-hour nursing day shift into three time blocks: 7am-11am, 11am-3pm, and 3pm-7pm.

The purposes of the study were to 1) quantify nurses’ time allocation on communication, hands-on tasks, and locations, 2) compare nurses’ allocation between different time blocks (7am-11am, 11am-3pm, and 3pm-7pm), 3) discover nurses’ multitasking and location traits, and 4) examine nurses’ phone call interruptions. To our knowledge, this was the first time motion study controlling the distribution of observation time as well as comparing nurses’ time allocation in different time blocks.

Setting and Sample

The study was conducted on a medical-surgical (med-surg) unit at a Mid-west academic medical center. We selected the 12-hour 7am to 7pm day shift, since a high volume of nursing activities is perceived to be typical during that time. We recruited registered nurses who met the following inclusion criteria: (1) full-time staff Registered Nurses (RNs) working at the academic medical center with more than two years of acute care nursing work experience, and (2) greater than or equal to six months of work experience on the study unit. We observed nurses in the general patient care and adjacent areas such as the nursing station, hallway, medication room, patient rooms, and supply areas. In these units, nurse patient ratios ranged from 1:4 to 1:5 depending on patient acuity.

Observed nursing activities

We observed nursing activities, such as hand-off (shift reporting), direct patient care (patient assessment, medication administration, procedures), indirect patient care (medication preparation, getting medication), interprofessional communication, and EHR review and charting. We also observed delegable nursing activities, such as vital sign and patient positioning (e.g., to patient care assistant), and delegable non-nursing activities such as records transfer and copying, which could be delegated to non-nursing team members (e.g., unit clerk). We did not document nurses’ hands-on tasks and communication in the isolation room (patient rooms in isolation), as observers were not allowed to follow nurses to the isolation room for safety reasons. The observable nursing activities list was refined iteratively and finalized during the training and trial observations. In total, we defined 11 types of communication, 32 hands-on tasks, and 14 locations. A list of example activities with definitions and start-end times has been published. 48

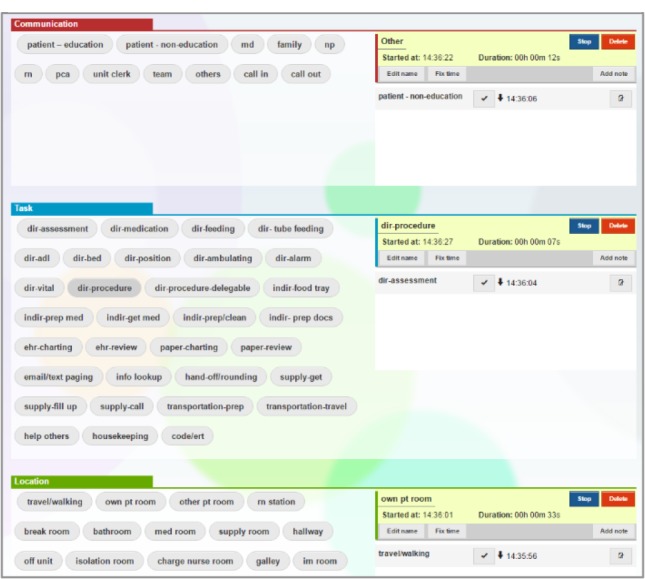

We loaded the defined nursing activities into TimeCaT ( Figure 1 ), 50 a validated electronic time capture tool developed to support data collection for time motion studies, optimized for touch enabled tablet computers and iPads. Observers used TimeCaT to document nursing activities with electronic timestamps, and capture multitasking and interruptions. 50 In TimeCaT, we were also able to visualize workflow and explore the location where nursing activities occurred. The workflow visualization illustrated nursing activities in three activity dimensions: communication, hands-on task and location, across the continuum of time. The data collected in TimeCaT allows us to portray nurses’ work: with whom the nurse was speaking (communication), while doing what (hands-on task), and at what location. 48

TimeCaT screenshot

Observers & Inter-observer reliability assessment (IORA)

Our observers were three nursing students, including one PhD nursing student and two undergraduate senior nursing students. Because of their nursing background and clinical experience, they were able to recognize and distinguish various nursing activities. Observers were required to attend training sessions and trial observations for at least 12 hours. They were also required to have three rounds of inter-observer reliability assessment to ensure data consistency before beginning data collection.

We established the inter-observer reliability via the IORA feature provided in TimeCaT. 50 TimeCaT IORA assesses four types of agreements: 1) proportion-kappa (P-K): evaluates the overall agreement on the proportion of time devoted to specific activities. P-K provides a global assessment of the agreement over time; 2) naming-kappa (N-K): evaluates the naming agreement on observed activities; N-K assesses observers’ understanding of activity definition in order to name an activity correctly; 3) duration-concordance correlation coefficient (D-CCC): evaluates the duration agreement of activities. D-CCC assesses observers’ agreement on the timing of the start and end of an event (activity), and results in duration agreement; 4) sequence-Needleman-Wunsch (S-NW): evaluates the sequence agreement of activities. S-NW focuses on the sequence/order of activities, which could help describe similarities among distinct workflows. The IORA provides quantitative reports as well as visualized side-by-side workflow comparison to assist in observers training. 48 Our IORA results indicated substantial agreement between our observers. 48

Data Collection

After approval from the local Institutional Review Board, observers obtained informed consent from the observed nurse as well as permission from patients to observe their care. No identifiable information or health records were collected. A typical 12-hour nursing day shift was split into three time blocks: 7am-11am, 11am-3pm, and 3pm-7pm. The 4-hour observation time block minimized the chance of un-balanced data if a 12-hour day shift happened to have a heavy or light workload, and also prevented observer fatigue. Each 4-hour observation was a one-on-one observation: one observer shadowed one nurse. Observers kept a certain distance from the observed nurse during the observation, but were not allowed to interact with the observed nurse in order to collect data reflecting true time duration and context. Observers arranged observations based on their availability about one to three times a week. Observers were suggested not to schedule observations at the same time to minimize distraction in the unit.

Data Analysis

We performed descriptive analysis to summarize nurses’ time allocation on communication, hands-on tasks, and locations. To examine whether there were differences in how nurses distributed their time in activities (ranking on frequency and duration) between time blocks (7am-11am, 11am-3pm, and 3pm-7pm), we used R to perform the Wilcoxon test to determine whether two time blocks have the same distribution of activities. To detect group differences on specific activities between time blocks (7am-11am, 11am-3pm, and 3pm-7pm), we performed the non-parametric independent-samples Kruskal-Wallis test with the criteria alpha set at 0.05. Post hoc pairwise comparison used Bonferroni correction. We used SPSS Statistics 25 and MS Excel for analysis and to generate graphs and tables.

We completed a total of 79 observations (316 hours) with 15 registered nurses. Among the 79 observations, nine were on Monday, 14 on Tuesday, 12 on Wednesday, 23 on Thursday, 16 on Friday, 2 on Saturday, and 3 on Sunday; 23 were 7am-11am, 30 were 11am-3pm, and 26 were 3pm-7pm.

Nurses’ time allocation on communication, hands-on tasks, and locations

We summarized nurses’ time allocation on communication, hands-on tasks, and locations ( Table 1 ). On average, in a 4-hour observation, nurses spent the most time communicating with patients (29.99 mins) and other nurses (26.68 mins). As for hands-on tasks, they spent the most time charting in EHR (31.63 mins) and reviewing information in EHR (21.51 mins), following by medication administration (15.70 mins) and getting medications (8.15 mins). They also spent about 13.52 mins on delegable tasks. When looking at locations, nurses spent most time in their patients’ room (60.17 mins) and at the nursing station (53.55 mins), following by in the hallway (37.74 min). We listed the top 10 tasks nurses performed in the hallway; nurses were charting and reviewing on EHR most of the time ( Table 1 a).

Nurses’ time allocation on communication, hands-on tasks, and location (mins per 4-hour obs.)

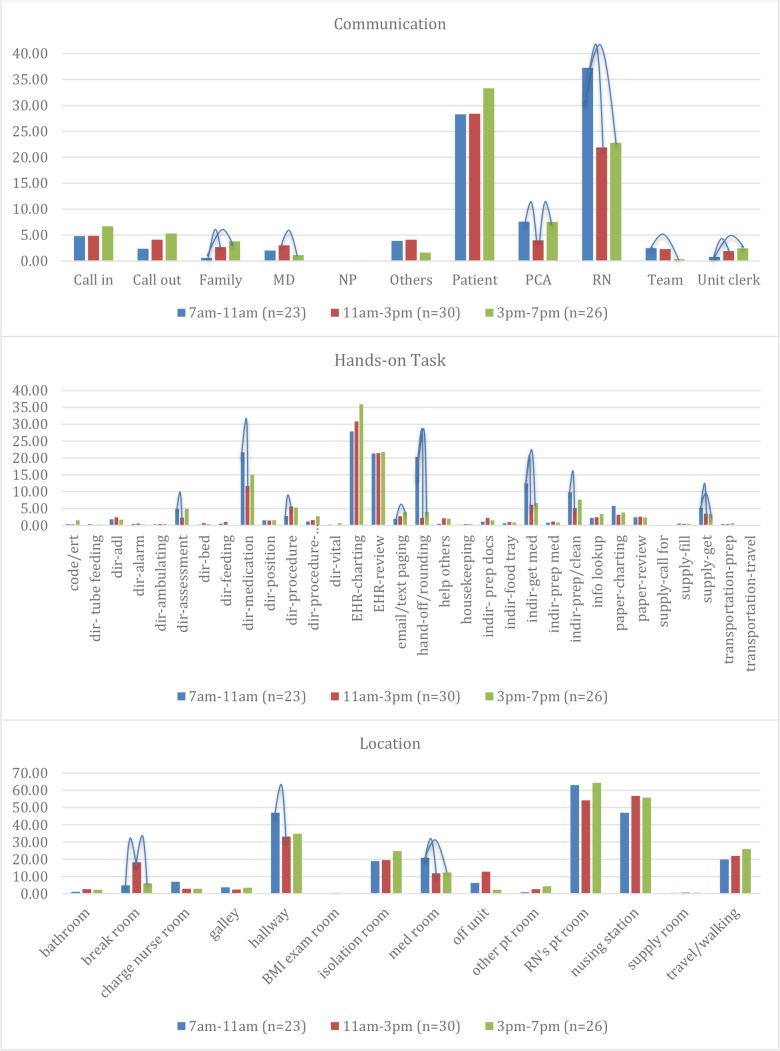

Comparison of time spent during 7am-11am, 11am-3pm, and 3pm-7pm

We also examined whether nurses spent time differently during 7am-11am, 11am-3pm, and 3pm-7pm time blocks. Figure 2 shows nurses’ time spent on communication, hands-on tasks, and locations. The Wilcoxon test only found a difference between 11am-3pm and 3pm-7pm on mean frequency of activities. In other words, nurses distributed their time in activities similarly across 7am-11am, 11am-3pm, and 3pm-7pm. The Kruskal-Wallis test show statistical significance in some group comparisons. The blue curves in Figure 1 represent group difference with statistical significance (p<0.05). For example, in the Communication bar chart, nurses spent less time communicating with family during 7am-11am than during 11am-3pm and 3pm-7pm. This could result from family visits taking place largely in the afternoon. Also, we found that nurses spent more time getting medications and supplies during 7am-11am, and spent more time in the med room during 7am-11am as well. Additionally, nurses spent more time in the hallway during 7am-11am, which can possibly be attributed to hand-offs and rounding that occurs in the hallway at this time.

Time spent (mins) on communication, hands-on tasks, and location

Multitasking

We looked into nurses’ multitasking traits as they engaged in communication and hands-on tasks simultaneously. We found that on average, nurses multitasked 59.95 minutes (37.17%) during 7-11am; 42.29 mins (26.25%) during 11am-3pm; and 51.62 mins (32.01%) during 3-7pm. The frequency and multitasking duration of hands-on tasks were higher during 7am-11am ( Table 2 ). Also, among the top 10 multitasks, seven are consistently in the top 10 ( Table 2 ). Nurses communicating with patients during medication administration, patient assessment, and charting were common multitasks; nurses also often communicated with other nurses while charting and reviewing in the EHR.

Frequency and duration of multitasking (communication + hands-on tasks)

Real time documentation has been a foreseen advantage as EHRs launched in hospitals. Nurses are encouraged or even required to document assessment findings and performed nursing activities in the EHR in the patient room. The electronic timestamps would reflect the time nursing activities performed. In our study, we found that among all EHR time, nurses spent the most time charting and reviewing in the EHR at the nurse station, followed by in the hallway, and then their patient rooms ( Table 4 ). This reflects an opportunity to define real time documentation, and identify obstacles hindering real time documentation.

Locations of EHR use

Communicating with Patients

As indicated in Figure 1 , nurses spent the most time communicating with patients. We examined what nurses were doing (hands-on tasks) while communicating with patients to understand how they spent time with patients. Table 5 list the top 10 hands-on tasks during the communication. Medication administration is the time when nurses interacted with patients the most (9.85 mins during 7am-11am). Note that each nurse was assigned 4 to 5 patients; more had 5 patients. Thus, the time available to devote to each patient would be less.

Top 10 hands-on tasks during comm. w/patients

Phone Call Interruptions

Interruption is common during patient care. Nurses are frequently interruptted by conversation, alarms or phone calls. Interruptions in patient rooms and the medication room are distractive, and can potentially lead to error. We analyzed the proportion of times (frequency) that nurses received phone calls while in patient rooms and the medication room. We found that nurses were interrupted by phone calls 16% of the times in patient rooms, and 10% of the times in the medication room ( Table 6 ).

Phone call interruption

To our knowledge, this was the first study using a time motion study to quantify and compare nurses’ time allocation in different time blocks (7-11am, 11-3pm, and 3-7pm). In addition, with our study design and approaches, we were able to detect multitasking and traits of nursing activities in different time blocks and locations. Our data also reflected the “busyness” of nurses’ work in the day shift.

Studies have been conducted to investigate nurses’ time allocation on nursing activities in order to describe and support nursing practice. Nurses spent approximately 34% of time in the patient room. 51 Lengthy documentation time has been a major challenge in the current EHR environment. Studies reported nurses spent 26.2 - 41% of their time on documentation 51 , 52 . However, these studies did not specify the distribution of the observation hours. It is unclear if the findings were representative for a longer timeframe (e.g. 7am-7pm, 5am-5pm). In our study, we found nurses spent 35% of their time in the patient room (including the isolation room) and spent about 25% of their time on documentation, including EHR and paper charting and review. Direct comparisons between our current study and previous work is challenging due to differences in methodologies, nursing specialty areas observed and variations in timing of observations relative to shift activities. As nurses’ work was not distributed equally across a 12-hour shift, we also found that greater frequency and duration in hands-on tasks were exhibited during 7am-11am. Future studies should consider the distribution of observation time to demonstrate representable and comparable findings.

Top-of-license practice

In 2010, The Institute of Medicine (IOM) published a report, The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health 53 recommending that “nurses should practice to the full extent of their education,” in other words, to work at the “top-of-license”. 54 , 55 Top-of-license nursing practice addresses how nurses should spend their time across the care continuum and suggest that “non-valued-added” activities should be delegated and executed by other healthcare personnel. 2 , 3 We conducted focus groups to explore nurses’ perception of their daily nursing activities. 56 Nurses expressed they were distracted and burdened by performing delegable and non-nursing activities due to insufficient staffing or inattention by other departments (dietary, housekeeping, transportation) or other nursing staff (patient care assistant and unit clerk), and wished to have more time being with their pateints. 56 Our time motion study confirmed these findings that nurses spent approximately 10% of time on delegable and non-nursing activities. Other studies reported similar findings of time spent on delegable activities (8-16%). 57 - 60 Although it does not seem to be a large amount, given that nurses’ spent 26% of time in patient rooms and 12.5% of time interacting with their four to five assigned patients. The 10% of time contributed to delegable or non-nursing activities could have been used more effectively for patient care. As the healthcare environment becomes complex, 49 future research should re-examine the current nursing practice to develop new strategies to improve nurses’ time allocation for high quality patient care. 30 , 61

Real time documentation

Timely documentation is essential for decision support and triggering alerts needed to draw attention on patient condition. Using EHR at the bedside was expected to increase the amount of time that nurses can spend in the patient room. However, nurses expressed the challenge of sharing their attention between patients and the EHR, resulting in more time on the computer screen. 62 Although real time documentation provided more thorough medical records, nurses’ still miss information because their communication broke down and nurses lost part of the conversation while typing in the EHR. 62 Nurses are also required to complete the mandatory documentation within a certain time frame, which competes with the time needed to fulfill patients’ needs. 63 Our study supports these nursing concerns in that nurses spent more time charting at the nursing station and the hallway than in patient rooms. Our study also shows a trend of increased documentation during 3pm-7pm. Although not statistically significant, these findings are consistent with a previous study reporting that afternoon was the peak time for nursing documentation. 64

Phone Call Interruption

Interruptions occur commonly in patient rooms and the medication room 43 , 44 and are threats to patient safety. 65 , 66 A recent study reported that medication administration was more likely to be rechecked because of interruptions, resulting in an decrease of wrong-dose errors, 67 this also implied work inefficiency. We also found that nurses communicated with patients primarily during medication administration. The conversation could be self-directed interruption (initiated by nurses), or unexpected interruptions (initiated by patients). We found that nurses spent 8-13% of the time in the medication room dealing with phone interruptions and 16-18% of the time in patient rooms dealing with phone interruptions. Interruptions by phone calls during patient care increases nurses’ stress. 68 Innovative solutions are necessary to minimize interruptions. For example, a wireless call system could provide more information (e.g. who and what the call is about) for nurses to manage interruptions. 68

Study Limitations

The study was limited to one unit in one hospital within one academic health system, thus limiting generalizability. Data collection occurred only over a four-month period subject to seasonal variations in hospital admissions. We also did not document nurses’ communication and hands-on tasks in the isolation room, as observers were not allowed access to the isolation room for safety reason. Participation bias was a limitation, as the study required nurses’ participation and consent. Also, observational research is limited by the human capacity to accurately record every action that occurs, especially in a high stress environment. 69 We may have missed some activities in rapidly changing hands-on tasks, communications or locations/movements. We could not guarantee 100% accuracy, but we minimized the inconsistency between observers through rigorous training, IORA, and clearly defining definitions of each activity.

The time motion study portrays nurses’ work in a 12-hours day shift. Our research also demonstrates a novel and quantifiable method of measuring multidimensional levels of nursing activities. The study results provide additional evidence to the growing body of literature on nurses’ time allocation, multitasking, patient care traits, and interruptions. This work can assist nursing leaders to develop strategies for transforming nursing practice through re-examination of nursing work and activities, and to maximize the potential of the nursing workforce by supporting nurses to truly practice at the top of their license.

Top 7 multitasks across all time blocks

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement: the project was funded by The American Nurses Foundation Nursing Research Grants Program.

- 1. Kudo Y, Yoshimura E, Shahzad MT, Shibuya A, Aizawa Y. Japanese professional nurses spend unnecessarily long time doing nursing assistants’ tasks. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2012;228(1):59–67. doi: 10.1620/tjem.228.59. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Storfjell JL, Ohlson S, Omoike O, Fitzpatrick T, Wetasin K. Non-value-added time: the million dollar nursing opportunity. J Nurs Adm. 2009;39(1):38–45. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0b013e31818e9cd4. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Storfjell JL, Omoike O, Ohlson S. The balancing act: patient care time versus cost. J Nurs Adm. 2008;38(5):244–249. doi: 10.1097/01.NNA.0000312771.96610.df. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Adler-Milstein J, DesRoches CM, Furukawa MF, et al. More Than Half of US Hospitals Have At Least A Basic EHR But Stage 2 Criteria Remain Challenging For Most. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ]

- 5. DesRoches CM, Charles D, Furukawa MF, et al. Adoption of electronic health records grows rapidly, but fewer than half of US hospitals had at least a basic system in 2012. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32(8):1478–1485. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0308. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Adler-Milstein J, Holmgren AJ, Kralovec P, Worzala C, Searcy T, Patel V. Electronic health record adoption in US hospitals: the emergence of a digital “advanced use” divide. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2017;24(6):1142–1148. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocx080. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Read-Brown S, Sanders DS, Brown AS, et al. Time-motion analysis of clinical nursing documentation during implementation of an electronic operating room management system for ophthalmic surgery. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2013;2013:1195–1204. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Banner L, Olney CM. Automated clinical documentation: does it allow nurses more time for patient care? Comput Inform Nurs. 2009;27(2):75–81. doi: 10.1097/NCN.0b013e318197287d. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Wong D, Bonnici T, Knight J, Gerry S, Turton J, Watkinson P. A ward-based time study of paper and electronic documentation for recording vital sign observations. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2017;24(4):717–721. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocw186. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Sanders DS, Read-Brown S, Tu DC, et al. Impact of an electronic health record operating room management system in ophthalmology on documentation time, surgical volume, and staffing. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132(5):586–592. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.8196. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Benner P, Sheets V, Uris P, Malloch K, Schwed K, Jamison D. Individual, practice, and system causes of errors in nursing: a taxonomy. J Nurs Adm. 2002;32(10):509–523. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200210000-00006. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Clarke SP, Aiken LH. Failure to rescue. Am J Nurs. 2003;103(1):42–47. doi: 10.1097/00000446-200301000-00020. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Ebright PR, Patterson ES, Chalko BA, Render ML. Understanding the complexity of registered nurse work in acute care settings. J Nurs Adm. 2003;33(12):630–638. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200312000-00004. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Higuchi KA, Donald JG. Thinking processes used by nurses in clinical decision making. J Nurs Educ. 2002;41(4):145–153. doi: 10.3928/0148-4834-20020401-04. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Potter P, Wolf L, Boxerman S, et al. An Analysis of Nurses’ Cognitive Work: A New Perspective for Understanding Medical Errors Advances in Patient Safety: From Research to Implementation (Volume 1: Research Findings) Rockville; p. MD2005. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Wolf LD, Potter P, Sledge JA, Boxerman SB, Grayson D, Evanoff B. Describing nurses’ work: combining quantitative and qualitative analysis. Hum Factors. 2006;48(1):5–14. doi: 10.1518/001872006776412289. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Tang Z, Mazabob J, Weavind L, Thomas E, Johnson TR. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2006. A time-motion study of registered nurses’ workflow in intensive care unit remote monitoring; pp. 759–763. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Capuano T, Bokovoy J, Halkins D, Hitchings K. Work flow analysis: eliminating non-value-added work. J Nurs Adm. 2004;34(5):246–256. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200405000-00008. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Blay N, Duffield CM, Gallagher R, Roche M. A systematic review of time studies to assess the impact of patient transfers on nurse workload. Int J Nurs Pract. 2014;20(6):662–673. doi: 10.1111/ijn.12290. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Westbrook JI, Ampt A, Williamson M, Nguyen K, Kearney L. Methods for measuring the impact of health information technologies on clinicians’ patterns of work and communication. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2007;129(Pt 2):1083–1087. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Westbrook JI, Duffield C, Li L, Creswick NJ. How much time do nurses have for patients? A longitudinal study quantifying hospital nurses’ patterns of task time distribution and interactions with health professionals. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:319. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-319. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Abbey M, Chaboyer W, Mitchell M. Understanding the work of intensive care nurses: a time and motion study. Aust Crit Care. 2012;25(1):13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2011.08.002. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Sakai Y, Yokono T, Mizokami Y, et al. Differences in the working pattern among wound, ostomy, and continence nurses with and without conducting the specified medical act: a multicenter time and motion study. BMC Nurs. 2016;15:69. doi: 10.1186/s12912-016-0191-1. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Wright G, O’Mahony D, Kabuya C, Betts H, Odama A. Nurses behaviour pre and post the implementation of data capture using tablet computers in a rural clinic in South Africa. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2015;210:803–807. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Tuinman A, de Greef MH, Krijnen WP, Nieweg RM, Roodbol PF. Examining Time Use of Dutch Nursing Staff in Long-Term Institutional Care: A Time-Motion Study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(2):148–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.09.002. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Gartemann J, Caffrey E, Hadker N, Crean S, Creed GM, Rausch C. Nurse workload in implementing a tight glycaemic control protocol in a UK hospital: a pilot time-in-motion study. Nurs Crit Care. 2012;17(6):279–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-5153.2012.00506.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Hendrich A, Chow MP, Skierczynski BA, Lu Z. A 36-hospital time and motion study: how do medical-surgical nurses spend their time? Perm J. 2008;12(3):25–34. doi: 10.7812/tpp/08-021. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Chan TC, Killeen JP, Vilke GM, Marshall JB, Castillo EM. Effect of mandated nurse-patient ratios on patient wait time and care time in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(5):545–552. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00727.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. van Oostveen CJ, Gouma DJ, Bakker PJ, Ubbink DT. Quantifying the demand for hospital care services: a time and motion study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:15. doi: 10.1186/s12913-014-0674-2. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Sochalski J. Is more better?: the relationship between nurse staffing and the quality of nursing care in hospitals. Med Care. 2004;42(2 Suppl):II67–73. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000109127.76128.aa. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Elganzouri ES, Standish CA, Androwich I. Medication Administration Time Study (MATS): nursing staff performance of medication administration. J Nurs Adm. 2009;39(5):204–210. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0b013e3181a23d6d. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Qian S, Yu P, Hailey DM. The impact of electronic medication administration records in a residential aged care home. Int J Med Inform. 2015;84(11):966–973. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2015.08.002. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Qian S, Yu P, Hailey DM, Wang N. Factors influencing nursing time spent on administration of medication in an Australian residential aged care home. J Nurs Manag. 2016;24(3):427–434. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12343. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 34. Popovici I, Morita PP, Doran D, et al. Technological aspects of hospital communication challenges: an observational study. Int J Qual Health Care. 2015;27(3):183–188. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzv016. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. de Ruiter HP, Demma JM. Nursing: the skill and art of being in a society of multitasking. Creat Nurs. 2011;17(1):25–29. doi: 10.1891/1078-4535.17.1.25. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. Bastian ND, Munoz D, Ventura M. A Mixed-Methods Research Framework for Healthcare Process Improvement. J Pediatr Nurs. 2016;31(1):e39–51. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2015.09.003. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 37. Draheim C, Hicks KL, Engle RW. Combining Reaction Time and Accuracy: The Relationship Between Working Memory Capacity and Task Switching as a Case Example. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2016;11(1):133–155. doi: 10.1177/1745691615596990. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 38. Edwards A, Fitzpatrick LA, Augustine S, et al. Synchronous communication facilitates interruptive workflow for attending physicians and nurses in clinical settings. Int J Med Inform. 2009;78(9):629–637. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2009.04.006. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 39. Spencer R, Coiera E, Logan P. Variation in communication loads on clinical staff in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;44(3):268–273. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.04.006. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 40. Berg LM, Kallberg AS, Goransson KE, Ostergren J, Florin J, Ehrenberg A. Interruptions in emergency department work: an observational and interview study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(8):656–663. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-001967. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 41. Walter SR, Li L, Dunsmuir WT, Westbrook JI. Managing competing demands through task-switching and multitasking: a multi-setting observational study of 200 clinicians over 1000 hours. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(3):231–241. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002097. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 42. McGillis Hall L, Pedersen C, Hubley P, et al. Interruptions and Pediatric Patient Safety. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2010;25(3):167–175. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2008.09.005. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 43. Johnson M, Sanchez P, Langdon R, et al. The impact of interruptions on medication errors in hospitals: an observational study of nurses. J Nurs Manag. 2017;25(7):498–507. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12486. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 44. Thomas L, Donohue-Porter P, Stein Fishbein J. Impact of Interruptions, Distractions, and Cognitive Load on Procedure Failures and Medication Administration Errors. J Nurs Care Qual. 2017;32(4):309–317. doi: 10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000256. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 45. McGillis Hall L, Pedersen C, Fairley L. Losing the moment: understanding interruptions to nurses’ work. J Nurs Adm. 2010;40(4):169–176. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0b013e3181d41162. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 46. Westbrook JI, Woods A, Rob MI, Dunsmuir WM, Day RO. Association of interruptions with an increased risk and severity of medication administration errors. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2010;170(8):683–690. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.65. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 47. Flynn F, Evanish JQ, Fernald JM, Hutchinson DE, Lefaiver C. Progressive Care Nurses Improving Patient Safety by Limiting Interruptions During Medication Administration. Crit Care Nurse. 2016;36(4):19–35. doi: 10.4037/ccn2016498. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 48. Yen PY, Kelley M, Lopetegui M, et al. Understanding and Visualizing Multitasking and Task Switching Activities: A Time Motion Study to Capture Nursing Workflow. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2016;2016:1264–1273. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 49. Kalisch BJ, Aebersold M. Interruptions and multitasking in nursing care. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2010;36(3):126–132. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(10)36021-1. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 50. Lopetegui M, Yen PY, Lai AM, Embi PJ, Payne PR. Time Capture Tool (TimeCaT): development of a comprehensive application to support data capture for Time Motion Studies. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2012;2012:596–605. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 51. Schenk E, Schleyer R, Jones CR, Fincham S, Daratha KB, Monsen KA. J Nurs Manag. 2017. Time motion analysis of nursing work in ICU, telemetry and medical-surgical units. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 52. Roumeliotis N, Parisien G, Charette S, Arpin E, Brunet F, Jouvet P. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2018. Reorganizing Care With the Implementation of Electronic Medical Records: A Time-Motion Study in the PICU. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 53. Institute of Medicine. Washington DC: National Academy of Sciences; 2011. The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health. [ Google Scholar ]

- 54. Company TAB. Achieving Top-of-License Nursing Practice. 2013. http://www.advisory.com/research/nursing-executive-center/studies/2013/achieving-top-of-license-nursing-practice . Accessed April 30th, 2015.

- 55. Company TAB. What is top-of-license nursing practice? 2014. http://www.advisory.com/research/nursing-executive-center/multimedia/video/2014/defining-top-of-license-practice . Accessed April 30th, 2015.

- 56. Buck J, Loversidge J, Chipps E, Gallagher-Ford L, Genter L, Yen P-Y. Journal of Nursing Administration. in press; 2018. Top-Of-License Nursing Practice Part 1: Describing Common Nursing Activities and Nurses’ Experiences that Hinder Top-of-License Practice. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 57. Schachner MB, Recondo FJ, Sommer JA, et al. Pre-Implementation Study of a Nursing e-Chart: How Nurses Use Their Time. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2015;216:255–258. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 58. Antinaho T, Kivinen T, Turunen H, Partanen P. Nurses’ working time use - how value adding it is? J Nurs Manag. 2015;23(8):1094–1105. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12258. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 59. Song X, Kim J-H, Despins L. A Time-Motion Study in an Intensive Care Unit using the Near Field Electromagnetic Ranging System. Paper presented at: Proceedings of the 2017 Industrial and Systems Engineering Conference2017. [ Google Scholar ]

- 60. Krugman M, Sanders C, Kinney LJ. Part 2: Evaluation and outcomes of an evidence-based facility design project. J Nurs Adm. 2015;45(2):84–92. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000162. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000162. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 61. Lavander P, Merilainen M, Turkki L. Working time use and division of labour among nurses and health-care workers in hospitals - a systematic review. J Nurs Manag. 2016;24(8):1027–1040. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12423. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 62. Duffy WJ, Kharasch MS, Du H. Point of care documentation impact on the nurse-patient interaction. Nurs Adm Q. 2010;34(1):E1–E10. doi: 10.1097/NAQ.0b013e3181c95ec4. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 63. Gaudet CA. Electronic Documentation and Nurse-Patient Interaction. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2016;39(1):3–14. doi: 10.1097/ANS.0000000000000098. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 64. Laitinen H, Kaunonen M, Astedt-Kurki P. The impact of using electronic patient records on practices of reading and writing. Health Informatics J. 2014;20(4):235–249. doi: 10.1177/1460458213492445. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 65. Hopkinson SG, Jennings BM. Interruptions during nurses’ work: A state-of-the-science review. Res Nurs Health. 2013;36(1):38–53. doi: 10.1002/nur.21515. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 66. Raban MZ, Westbrook JI. Are interventions to reduce interruptions and errors during medication administration effective?: a systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(5):414–421. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002118. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 67. Blignaut AJ, Coetzee SK, Klopper HC, Ellis SM. Medication administration errors and related deviations from safe practice: an observational study. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26(21-22):3610–3623. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13732. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 68. Klemets J, Evjemo TE. Technology-mediated awareness: facilitating the handling of (un)wanted interruptions in a hospital setting. Int J Med Inform. 2014;83(9):670–682. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2014.06.007. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 69. Vankipuram M, Kahol K, Cohen T, Patel VL. Toward automated workflow analysis and visualization in clinical environments. J Biomed Inform. 2011;44(3):432–440. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2010.05.015. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- PDF (1.1 MB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

- 1.866.411.2159

- Online Pediatric Nurse Practitioner (PNP) Program

- Online Family Nurse Practitioner (FNP)

- Online Psychiatric Mental Health Nurse Practitioner Program (PMHNP)

- Online Women’s Health Nurse Practitioner Program (WHNP)

- Online Adult Gerontology – Primary Care Nurse Practitioner (AGPCNP) Program

- Adult Gerontology Acute Care Nurse Practitioner (AGACNP)

- Online Master’s Degrees Overview

- Master’s in Applied Behavior Analysis

- Online Master of Science in Product Management

- Online Master of Science in Nursing

- Online Master of Social Work

- Online Doctoral Degrees Overview

- Online BSN to Doctor of Nursing Practice

- Online MSN to Doctor of Nursing Practice

- Online Certificate Programs Overview

- Online ABA Certificate

- Online Introduction to Product Management Certificate

- Online Nursing Certificate Programs

- About Regis College

- Corporate Partners Tuition Discount

- Federal Employee Program

- Military & Veterans Tuition Discount Program

- Faculty Directory

Nurse Time Management: Tips and Techniques for Nurses and Nursing Students

May 4, 2023

View all blog posts under Articles | View all blog posts under Infographics | View all blog posts under Master of Science in Nursing

Recommended nurse -to-patient ratios help ensure such time is available to nurses. The appropriate nurse-to-patient ratio depends on the type of nursing care being provided. For example, in a critical care unit, nurses should have no more than two patients, whereas in an emergency department, nurses can safely care for up to four patients.

Unfortunately, the ongoing nursing shortage has disrupted these nurse-to-patient ratios in many cases. The lack of nurse educators and the aging nursing workforce, which exacerbate this shortage, make the need for more nurses to pursue advanced roles particularly urgent.

By putting into practice effective nurse time management strategies, however, nurses can improve the efficiency of their care delivery and potentially shrink the nurse-to-patient ratio gap.

What Is Nurse Time Management?

In nursing, time management refers to how nurses use and organize their time. Effective time management typically requires nurses to adopt a set of behaviors that help them to work smarter, not necessarily harder. With the right habits in place, nurses can increase their efficiency and boost their productivity.

The behaviors key to effective time management tend to revolve around:

- Setting goals

- Prioritizing tasks

- Identifying ways to save time

Developing time management skills in the above areas can help nurses balance heavy workloads and meet the demands made on their time.

To gain further insight into nurse time management, nurses may find it useful to examine its components and how they relate to various nursing tasks.

The Purpose of Nurse Time Management

Nurses frequently have tight time blocks to handle a great number of responsibilities — everything from taking patient medical histories and checking diagnostic tests to mentoring newer members of their nursing teams.

Effective time management can empower nurses to carry out more tasks in less time. It can also help nurses adapt to the constraints imposed upon them without compromising the care they deliver.

Benefits of Nurse Time Management

Beyond making it possible for nurses to carry out their duties in the face of time crunches, time management skills can help nurses improve their job performance. Enhanced job performance typically leads to increased motivation at work and, in turn, greater job satisfaction.

What Effective Time Management Can Achieve

Effective time management can correct poor time allocation and lead to better clinical decisions. That’s because, when nurses manage their time well, they feel less pressured. This gives them the space to think more clearly and make measured choices based on their past experiences, their knowledge of the patient, the context of the situation, and other considerations.

Conversely, a lack of time can result in nurses only attending to the tasks they must do, and forgoing the tasks they should do related to patient care. For example, a nurse may make sure to turn patients to prevent them from getting bed sores, but they may skip having conversations with patients that provide needed emotional support and reassurance.

Effective time management can enable nurses to spend more time with their patients and get to the less urgent nursing tasks that are still very important.

Why Is Time Management in Nursing So Important?

Nurse time management not only affects a nurse’s ability to effectively carry out their duties. Time management can also impact patient safety, professional advancement, and successful collaboration with other care providers.

Following are some other important advantages of effective nurse time management.

Reducing Patient Care Gaps

As mentioned above, the nursing shortage has resulted in patient care gaps . With nurses often facing less-than-ideal nurse-to-patient ratios, some patients end up receiving care that falls short of best practices. These breakdowns in care can increase the risk of adverse health outcomes for patients.

Time constraints often contribute to gaps in care, and with fewer nurses on duty, individual nurses have less time than ever before. As a result, nurses may struggle to find the time to fully discuss preventive care with their patients, for example, or adequately explain a diagnosis. This can result in patients not getting a needed colorectal screening or a recommended mammogram.

However, sharp time management skills can help nurses prevent such lapses in care. By redefining how they work and adopting habits that improve their efficiency, nurses can create more time in their schedules, allowing them to engage in best practices that keep care gaps in check.

Improved Patient Care

Time management can reduce the anxiety nurses experience in the course of doing their job. This helps nurses regulate their emotions and better cope with challenging situations as they arise. This also can lead to:

- Fewer errors in care delivery

- Enhanced communication with colleagues and patients

- Improved analysis of data in decision-making

Improvements in Facility Operations and Operational Management

Nurses serve as the primary providers of care at hospitals and deliver most long-term care in the U.S. They also make up the largest segment of health care workers . Inevitably, they have a huge impact on how health care organizations run.

Nursing practices can affect the efficiency of day-to-day operations at any medical facility. For example, nursing practices can impact patient wait times, operational costs , and the use of resources. That being the case, effective nurse time management can:

- Save a health care organization money

- Increase patient satisfaction

- Help reduce wasteful uses of supplies and equipment

Potential Improvements in Patient Outcomes

Health care organizations have a number of ways they can improve their patients’ outcomes — for example, by increasing the efficiency of their facility’s operations, making efforts to keep patients satisfied, and providing consistently high-quality care, to name a few. The central role nurses play in health care means they can make a huge difference in each of these areas.

From preventing medical mistakes to implementing evidence-based treatments, with the right time management skills, nurses help ensure that their organizations deliver optimal patient outcomes.

8 Tips for Nurse Time Management

Given the many benefits of effective time management, it makes sense for nurses to invest time and energy into cultivating their skills in this area. Such an investment can help nurses be more at ease in their work and, in turn, feel more joy doing what they do best.

The following time management tips for nurses serve as an excellent starting point for any nurse ready to take a proactive approach to improving their experience on the job.

1. Prioritize Tasks with To-Do Lists

Nurses interact with large amounts of information throughout their shifts. They also have many tasks to keep track of. Trying to store everything through sheer memorization can wear a nurse out. By taking notes , making to-do lists that prioritize items according to urgency, and marking to whom each task could be delegated, nurses free up space in their minds and lighten their mental load. This can improve their mental agility.

To-do lists enable nurses to remember details they may otherwise forget. These details can better inform the interventions and treatments they decide to use and lead to better results in patient care as a result.

When writing to-do lists, nurses can ask themselves a series of questions to help them prioritize their schedules, such as:

- What should I do first and why?

- What does the patient need most?

- If this isn’t done now, what’s the worst that could happen?

2. Cluster Care

A nurse clusters care for a patient by completing a slew of important tasks in a single visit. So, rather than making individual stops to check a patient’s vitals, assist them with toileting, and administer medication, a nurse takes care of all these items at once.

By clustering care, nurses can avoid unnecessary back-and-forth movements and, in turn, save time. This results in fewer interruptions for patients as well, which can help them rest better.

Research has shown that because clustering care limits how many times a nurse goes in and out of a patient’s room, this habit also can lower the risk of nurses catching infectious diseases.

In addition to keeping nurses safer, clustering care can keep patients safer too. A recent study found that, in certain cases, clustering care can reduce a patient’s risk of acquiring urinary tract infections and shorten the length of time they require a urinary catheter.

3. Act Proactively

Unexpected events and setbacks tend to occur with some regularity in nursing. For that reason, nurses need to try and stay one step ahead of any potential problems by acting proactively to protect patient safety.

Proactive nursing comes down to taking control of situations, so patients receive the care they need when they need it. It also means seizing opportunities when they appear, and anticipating what could go wrong.

For example, when work slows down, a nurse can use this time to tackle low-priority tasks and, in this way, help create buffers should unexpected events unfold. Or a nurse who suspects a patient needs a specific diagnostic test, such as a chest X-ray, may invite a doctor to conduct an evaluation in the triage room of an emergency department to expedite care.

A proactive approach can be a crucial nurse time management technique, resulting in less work for nurses because it helps limit complications that may occur in patients’ conditions. It can also lead to quicker handling of complications, which can prevent bottlenecks from forming that may require reorganizing patients and create even more delays in care delivery.

4. Use Effective Organization

Effective organization can help nurses gain more control over how they spend their day. By organizing one’s workspace and establishing routines that create order and impose a logical structure on how tasks are completed, nurses can work much more efficiently. This efficiency can increase the time nurses have to interact with patients.

Being organized can also give nurses better visibility when it comes to seeing the big picture of patients’ conditions and needs. This visibility can help nurses make more astute clinical decisions that generate better patient outcomes.

Useful organizational strategies can include:

- Developing a system for storing patient records and documents so time isn’t wasted trying to locate important information

- Starting a shift by grouping tasks according to urgency, making it easier to prioritize and cluster care for each patient

- Implementing routines that ensure necessary medications, supplies, and equipment are ready and quickly accessed

Additionally, at the start of each shift, nurses can organize their work with time in mind by considering questions such as:

- What nursing interventions can I implement while I’m waiting for medical orders?

- What resources can be used to complete the day’s work that can improve efficiency?

5. Perform Hourly Rounding

Planned hourly patient visits help nurses ensure their patients are safe, each patient’s required routine care has been performed, and each patient’s comfort has been checked. A best practice in nursing, hourly rounding helps nurses control their time by preemptively addressing patients’ needs.

This time management tip for nurses both lowers the number of times patients ring for assistance and reduces patient falls. While making hourly rounds on day and night shifts , nurses who keep in mind the five P’s will reap the most time-saving benefits from the practice. Issues to address and questions to consider when making hourly rounds include:

Is the patient experiencing pain? If so, at what level? Nurses can discuss options for addressing the pain. They can reaffirm their intent to make the patient as comfortable as possible.

Does the patient need any assistance using the bathroom? Nurses can assure patients that their bathroom needs are a priority and that they can get whatever help they need.

Positioning

Is the patient in a comfortable position? Nurses may need to reposition patients to protect their skin. This may involve pulling them up, placing pillows under their limbs, or adjusting the bed’s position up or down.

Personal Items

Can the patient reach their various personal items, such as their phone, lip balm, or water? Nurses can ask patients if they have everything they need and offer to place a specific item closer.

Does the patient have the privacy they desire? Nurses can ask patients if they want the curtains drawn, the door shut, and so on. They can also reiterate their desire to respect the patient’s privacy needs.

6. Seek Assistance

Fellow team members can often provide support that helps nurses strengthen their time management skills. Talking to colleagues about their approaches to various tasks can enable nurses to learn new techniques and processes that increase their efficiency and eliminate redundancies.

Additionally, asking colleagues to provide constructive feedback can also give nurses useful insights about where they may improve their management of particular tasks.

7. Use Technology Efficiently

Nurses have a huge range of technological tools to help them prioritize their work, stay organized, increase their productivity, track their habits, and the list goes on. For many busy nurses, technology serves as a great time management hack.

To start, nurse time management apps can help nurses plan their days, create to-do lists, set reminders, and more. These apps allow nurses to keep track of their various patient care duties and prevent time-consuming oversights.

Additionally, many health care organizations use software to record patient data. These programs often have time-tracking features that can help nurses assess how they’re spending their time and make changes as necessary.

Alongside time management apps, nurses can take advantage of apps that specifically cater to the health care community. Some of these apps provide medical information, including the side effects of certain medications to drug interactions. Others deliver the latest medical news, translate medical terms into different languages, and give descriptions of diseases and their symptoms.

Using these tools can empower nurses to communicate with diverse patient populations, verify information, better educate patients, and develop time-saving habits.

8. Take Breaks

Though perhaps counterintuitive, taking breaks can actually help nurses save time. While some nurses choose to skip lunch and forgo even a brief recess from their duties, this can sometimes do more harm than good.

Taking time out to rest every so often lowers a nurse’s risk of experiencing an on-the-job injury and making an error. Breaks can also help reduce fatigue and burnout. Without a chance to recover and unwind, nurses may struggle to do their best work. Additionally, nurse burnout not only harms a nurse’s well-being and overall morale, it also contributes to the current nursing shortage.

Some tips for taking breaks that can help nurses feel reenergized include:

- Eating a healthy snack.

- Taking a walk outside.

- Meditating.

- Engaging in non-work-related conversations with coworkers.

- Listening to music.

Add This Infographic to Your Site

A nurse needs a solid set of core competencies in order to develop effective time management strategies. The following skills can transform good time management ideas into excellent time management strategies: delegation, organization, communication, critical thinking, and technical expertise.

Resources for Nurse Time Management

Nurses interested in learning more about time management techniques can explore the following resources:

- “ Time Management Tips for New Nurses ” is a video lesson highlighting techniques for nurse time management in different settings.

- The article “ Two Tactics for Time Management and Stress Reduction ” offers ideas for setting up morning routines and defining nonnegotiable tasks that can help nurses manage their time.

- The article “ 20+ of the Best Mobile Apps for Nurses ” provides links and descriptions for an array of apps that can help nurses unwind, perform well on the job, and stay organized.

- Published by Entrepreneur , “ 15 of the Best Time Management and Productivity Books of All Time ” lists the top books for learning how to better budget one’s time and work more productively.

- This Time Management tool kit includes a collection of articles, infographics, videos, and self-assessments, all focused on techniques for improving time management.

- The article “ 18 Time Management Tips, Strategies, and Quick Wins to Get Your Best Work Done ” describes specific techniques nurses can use to stay organized and use their time efficiently, such as the “Eat the Frog” strategy and the Pareto principle.

- “ Modeling and Evaluation of Clustering Patient Care Into Bubbles ” describes research that explores models for efficiently clustering patient care.

- The video “ 8 Behaviors of Purposeful Hourly Rounding ” provides a 26-minute training on hourly rounding for nurses.

- The article “ 3 Best Tips for Prioritizing the Needs of Your Patients ” covers techniques for prioritizing patient needs.

Important Nurse Time Management Skills

Developing certain key skills can have a significant impact on a nurse’s ability to successfully manage their time. Applying these skills can also greatly improve the efficiency with which nurses perform a host of tasks.

Knowing how to delegate helps nurses manage their workloads. Effective delegation allows nurses to focus on the tasks that require their specific clinical knowledge and assign less complex responsibilities to others.

Essential to teamwork, delegation helps nurses make sure the right tasks are completed by the right people at the right time. Handing off responsibilities to nurse assistants or other health care professionals can enable nurses to tackle tasks that need their immediate attention without getting distracted by less pressing matters.

This can prevent potential delays in the completion of less urgent duties, which often lead to a backlog of tasks that can congest workflows and slow everything down.

The National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) recommends that nurses keep in mind the five rights of delegation when allocating tasks to others. These rights are:

The Right Task

Consider if the delegated task falls within the colleague’s scope of practice and job description. Then ensure the task matches the patient’s care plan.

The Right Circumstance

Only delegate tasks for patients in stable condition and whose status does not require extra safety precautions. This protects patients from unnecessary risks.

The Right Person

Make sure to delegate tasks only to individuals who have already demonstrated their capacity to perform the task. Whoever performs the task must have the proper training, education, and skill set.

The Right Direction and Communication

Provide explicit instructions for the task to the person it has been delegated to, confirm their understanding, and answer any questions they have about what the task entails. Expectations for the task must also be clear.

The Right Supervision and Evaluation

Be available to oversee the delegated task when necessary. Offer support and feedback to ensure the work complies with the proper standards of care and procedures.

Communication

Proper communication is a crucial aspect of nursing. It allows nurses to convey critical information about diagnoses, symptoms, and treatment options to patients, their families, and other health care providers. It also enables nurses to provide emotional support to those under their care and clinical support to those working alongside them.

Effective communication is also an important skill for nurse time management. First, it helps limit misunderstandings that can require team members to undo and redo tasks. By communicating clearly with patients, which also involves active listening, nurses pick up on subtle details that can help them understand and then address patients’ needs more quickly.

Additionally, strong communication skills allow nurses to work more productively. Rather than having to spend time clearing up confusion about task delegations, patient symptoms, follow-up instructions, and medications — all of which can lead to poor patient outcomes and readmissions — nurses can focus on conducting assessments, implementing care plans, and completing daily charting.

Critical Thinking

Nurses with strong critical thinking skills can better analyze patients’ conditions and responses to treatment. They can also more accurately anticipate the associated outcomes and risks of those conditions and treatments. This gives them a more precise and complete understanding of their patients’ situations. In turn, these nurses have sharper judgment. They can then act more swiftly to execute evidence-based interventions if needed.

Analytical nurses catch problems early and think for themselves. Rather than blindly following orders, they evaluate each situation to determine the right course of action. For example, after seeing that a patient’s blood pressure has dropped below acceptable levels, a strong critical thinker won’t simply administer the patient’s prescribed blood pressure medication. Instead, they’ll consult with the patient’s physician about how to stop the patient’s blood pressure from dropping even further.

This ability to think for oneself analytically allows nurses to prevent situations from getting out of hand. Averting problems and addressing issues quickly results in fewer complicated and time-consuming clinical situations arising.

Technical Expertise

Possessing technical expertise streamlines nursing care by eliminating unnecessary pauses and gaps that can lead to errors and compromise patient safety. Nurses with emergency care skills or advanced knowledge of how to use medical equipment, for example, can jump into situations without delay.

In today’s nursing landscape, nurses need to be comfortable using a range of technologies designed to boost the efficiency of everything from recording patient data to monitoring patient vitals. When nurses hone their ability to use these tools, it can enhance communication within their teams and speed up the time it takes to complete routine tasks.

For example, by using real-time location systems, nurses can avoid wasting time trying to track down an electrocardiogram machine, IV unit, or other supplies or equipment they need.

Time Management for Nursing Students

Nursing students have rigorous schedules. Managing demanding coursework, labs, and clinical experiences can leave many nursing students feeling overwhelmed, especially those who lack strong time management skills.

That being said, by developing effective strategies for managing their time while in school, nursing students can prepare themselves for career success .

In addition to helping students stay on track with their academic goals, cultivating strategic time management habits helps foster an efficient approach to nursing. These habits lay the foundation for more efficient nursing practice in the real world.

Key Time Management Skills for Nursing Students

So what does time management for nursing students entail? Beyond getting enough sleep and setting up a disciplined study routine, nursing students can benefit from focusing on time management skills specific to the nursing field.

Learn Prioritization Strategies in Nursing School

As already discussed, prioritization is an essential part of effective nursing practice. Accurately identifying what tasks to complete first and why doesn’t just save nurses extra hassles. In nursing, it can mean the difference between life and death.

In nursing school, prioritization can make it easier for students to meet deadlines and effectively budget their time. This, in turn, can alleviate some of the pressure nursing students feel.

To sharpen their prioritization skills, nursing students may want to examine how nurses in the field approach prioritization. When planning their work, nurses who effectively prioritize their tasks ask themselves a series of questions:

- What important items are dependent on the completion of other specific actions?

- What tasks are time-sensitive?

- What is essential to achieving the desired outcome?

Nursing students can apply these same guiding questions to their own work. This can help them organize their to-do lists, block their time appropriately, and realize their academic goals.

Build the Confidence Needed for Delegation

Being comfortable delegating requires a good deal of confidence, but it’s key to effective teamwork in nursing. Gaining this confidence takes time. However, nursing students can take a number of actions to start building it before they’re on the job. To begin, nursing students can practice delegation during the learning process.

For example, nursing students can volunteer to lead when group work is assigned. They can ask probing questions about appropriate delegation to increase their understanding and, in turn, their confidence. They can also simulate delegation with their peers during clinical experiences.

Resources for Developing Time Management Strategies

The following resources can help nursing students develop effective time management strategies.

- The listicle “ 20 Best Time Management Podcasts ” offers a list of podcasts that all focus on time management hacks.

- Picmonic , a service for nursing and medical students, offers free and paid subscriptions to a system that uses stories, pictures, and quizzes to fast-track learning about key nurse time management topics such as delegation.

- “ Patient Prioritization — Nursing Leadership ” is a teaching video that discusses models of patient prioritization.

- The journal article “ Time Management Strategies for New Nurses ” offers strategies and tips new nurses can use to improve their time management skills.

Cultivate the Right Time Management Skills to Thrive as a Nurse

Effectively budgeting one’s time factors into the success of almost every professional. Effective time management in nursing, however, is more than just a helpful skill. It’s imperative for balancing the workloads and demands made on nurses.

By mastering time management skills, nurses can flourish at the professional level and deliver the highest standard of patient care.

Infographic Sources:

Chron, “Time Management Skills for Nurses”

EMedCert, “10 Time Management Tips for Nurses”

My American Nurse , “New Graduate Nurse Time Management”

StatPearls, “Five Rights of Nursing Delegation”

Let’s move forward

Wherever you are in your career and wherever you want to be, look to Regis for a direct path, no matter your education level. Fill out the form to learn more about our program options or get started on your application today.

IMAGES

VIDEO