What Is Research Design?

A Plain-Language Explainer (With Examples)

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewers: Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) & Kerryn Warren (PhD) | April 2023

Overview: Research Design 101

What is research design.

- Research design types for quantitative studies

- Video explainer : quantitative research design

- Research design types for qualitative studies

- Video explainer : qualitative research design

- How to choose a research design

- Key takeaways

Research design refers to the overall plan, structure or strategy that guides a research project , from its conception to the final data analysis. A good research design serves as the blueprint for how you, as the researcher, will collect and analyse data while ensuring consistency, reliability and validity throughout your study.

Understanding different types of research designs is essential as helps ensure that your approach is suitable given your research aims, objectives and questions , as well as the resources you have available to you. Without a clear big-picture view of how you’ll design your research, you run the risk of potentially making misaligned choices in terms of your methodology – especially your sampling , data collection and data analysis decisions.

The problem with defining research design…

One of the reasons students struggle with a clear definition of research design is because the term is used very loosely across the internet, and even within academia.

Some sources claim that the three research design types are qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods , which isn’t quite accurate (these just refer to the type of data that you’ll collect and analyse). Other sources state that research design refers to the sum of all your design choices, suggesting it’s more like a research methodology . Others run off on other less common tangents. No wonder there’s confusion!

In this article, we’ll clear up the confusion. We’ll explain the most common research design types for both qualitative and quantitative research projects, whether that is for a full dissertation or thesis, or a smaller research paper or article.

Research Design: Quantitative Studies

Quantitative research involves collecting and analysing data in a numerical form. Broadly speaking, there are four types of quantitative research designs: descriptive , correlational , experimental , and quasi-experimental .

As the name suggests, descriptive research design focuses on describing existing conditions, behaviours, or characteristics by systematically gathering information without manipulating any variables. In other words, there is no intervention on the researcher’s part – only data collection.

For example, if you’re studying smartphone addiction among adolescents in your community, you could deploy a survey to a sample of teens asking them to rate their agreement with certain statements that relate to smartphone addiction. The collected data would then provide insight regarding how widespread the issue may be – in other words, it would describe the situation.

The key defining attribute of this type of research design is that it purely describes the situation . In other words, descriptive research design does not explore potential relationships between different variables or the causes that may underlie those relationships. Therefore, descriptive research is useful for generating insight into a research problem by describing its characteristics . By doing so, it can provide valuable insights and is often used as a precursor to other research design types.

Correlational Research Design

Correlational design is a popular choice for researchers aiming to identify and measure the relationship between two or more variables without manipulating them . In other words, this type of research design is useful when you want to know whether a change in one thing tends to be accompanied by a change in another thing.

For example, if you wanted to explore the relationship between exercise frequency and overall health, you could use a correlational design to help you achieve this. In this case, you might gather data on participants’ exercise habits, as well as records of their health indicators like blood pressure, heart rate, or body mass index. Thereafter, you’d use a statistical test to assess whether there’s a relationship between the two variables (exercise frequency and health).

As you can see, correlational research design is useful when you want to explore potential relationships between variables that cannot be manipulated or controlled for ethical, practical, or logistical reasons. It is particularly helpful in terms of developing predictions , and given that it doesn’t involve the manipulation of variables, it can be implemented at a large scale more easily than experimental designs (which will look at next).

Need a helping hand?

Experimental research design is used to determine if there is a causal relationship between two or more variables . With this type of research design, you, as the researcher, manipulate one variable (the independent variable) while controlling others (dependent variables). Doing so allows you to observe the effect of the former on the latter and draw conclusions about potential causality.

For example, if you wanted to measure if/how different types of fertiliser affect plant growth, you could set up several groups of plants, with each group receiving a different type of fertiliser, as well as one with no fertiliser at all. You could then measure how much each plant group grew (on average) over time and compare the results from the different groups to see which fertiliser was most effective.

Overall, experimental research design provides researchers with a powerful way to identify and measure causal relationships (and the direction of causality) between variables. However, developing a rigorous experimental design can be challenging as it’s not always easy to control all the variables in a study. This often results in smaller sample sizes , which can reduce the statistical power and generalisability of the results.

Moreover, experimental research design requires random assignment . This means that the researcher needs to assign participants to different groups or conditions in a way that each participant has an equal chance of being assigned to any group (note that this is not the same as random sampling ). Doing so helps reduce the potential for bias and confounding variables . This need for random assignment can lead to ethics-related issues . For example, withholding a potentially beneficial medical treatment from a control group may be considered unethical in certain situations.

Quasi-Experimental Research Design

Quasi-experimental research design is used when the research aims involve identifying causal relations , but one cannot (or doesn’t want to) randomly assign participants to different groups (for practical or ethical reasons). Instead, with a quasi-experimental research design, the researcher relies on existing groups or pre-existing conditions to form groups for comparison.

For example, if you were studying the effects of a new teaching method on student achievement in a particular school district, you may be unable to randomly assign students to either group and instead have to choose classes or schools that already use different teaching methods. This way, you still achieve separate groups, without having to assign participants to specific groups yourself.

Naturally, quasi-experimental research designs have limitations when compared to experimental designs. Given that participant assignment is not random, it’s more difficult to confidently establish causality between variables, and, as a researcher, you have less control over other variables that may impact findings.

Research Design: Qualitative Studies

There are many different research design types when it comes to qualitative studies, but here we’ll narrow our focus to explore the “Big 4”. Specifically, we’ll look at phenomenological design, grounded theory design, ethnographic design, and case study design.

Phenomenological design involves exploring the meaning of lived experiences and how they are perceived by individuals. This type of research design seeks to understand people’s perspectives , emotions, and behaviours in specific situations. Here, the aim for researchers is to uncover the essence of human experience without making any assumptions or imposing preconceived ideas on their subjects.

For example, you could adopt a phenomenological design to study why cancer survivors have such varied perceptions of their lives after overcoming their disease. This could be achieved by interviewing survivors and then analysing the data using a qualitative analysis method such as thematic analysis to identify commonalities and differences.

Phenomenological research design typically involves in-depth interviews or open-ended questionnaires to collect rich, detailed data about participants’ subjective experiences. This richness is one of the key strengths of phenomenological research design but, naturally, it also has limitations. These include potential biases in data collection and interpretation and the lack of generalisability of findings to broader populations.

Grounded Theory Research Design

Grounded theory (also referred to as “GT”) aims to develop theories by continuously and iteratively analysing and comparing data collected from a relatively large number of participants in a study. It takes an inductive (bottom-up) approach, with a focus on letting the data “speak for itself”, without being influenced by preexisting theories or the researcher’s preconceptions.

As an example, let’s assume your research aims involved understanding how people cope with chronic pain from a specific medical condition, with a view to developing a theory around this. In this case, grounded theory design would allow you to explore this concept thoroughly without preconceptions about what coping mechanisms might exist. You may find that some patients prefer cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) while others prefer to rely on herbal remedies. Based on multiple, iterative rounds of analysis, you could then develop a theory in this regard, derived directly from the data (as opposed to other preexisting theories and models).

Grounded theory typically involves collecting data through interviews or observations and then analysing it to identify patterns and themes that emerge from the data. These emerging ideas are then validated by collecting more data until a saturation point is reached (i.e., no new information can be squeezed from the data). From that base, a theory can then be developed .

Ethnographic design involves observing and studying a culture-sharing group of people in their natural setting to gain insight into their behaviours, beliefs, and values. The focus here is on observing participants in their natural environment (as opposed to a controlled environment). This typically involves the researcher spending an extended period of time with the participants in their environment, carefully observing and taking field notes .

All of this is not to say that ethnographic research design relies purely on observation. On the contrary, this design typically also involves in-depth interviews to explore participants’ views, beliefs, etc. However, unobtrusive observation is a core component of the ethnographic approach.

As an example, an ethnographer may study how different communities celebrate traditional festivals or how individuals from different generations interact with technology differently. This may involve a lengthy period of observation, combined with in-depth interviews to further explore specific areas of interest that emerge as a result of the observations that the researcher has made.

As you can probably imagine, ethnographic research design has the ability to provide rich, contextually embedded insights into the socio-cultural dynamics of human behaviour within a natural, uncontrived setting. Naturally, however, it does come with its own set of challenges, including researcher bias (since the researcher can become quite immersed in the group), participant confidentiality and, predictably, ethical complexities . All of these need to be carefully managed if you choose to adopt this type of research design.

Case Study Design

With case study research design, you, as the researcher, investigate a single individual (or a single group of individuals) to gain an in-depth understanding of their experiences, behaviours or outcomes. Unlike other research designs that are aimed at larger sample sizes, case studies offer a deep dive into the specific circumstances surrounding a person, group of people, event or phenomenon, generally within a bounded setting or context .

As an example, a case study design could be used to explore the factors influencing the success of a specific small business. This would involve diving deeply into the organisation to explore and understand what makes it tick – from marketing to HR to finance. In terms of data collection, this could include interviews with staff and management, review of policy documents and financial statements, surveying customers, etc.

While the above example is focused squarely on one organisation, it’s worth noting that case study research designs can have different variation s, including single-case, multiple-case and longitudinal designs. As you can see in the example, a single-case design involves intensely examining a single entity to understand its unique characteristics and complexities. Conversely, in a multiple-case design , multiple cases are compared and contrasted to identify patterns and commonalities. Lastly, in a longitudinal case design , a single case or multiple cases are studied over an extended period of time to understand how factors develop over time.

How To Choose A Research Design

Having worked through all of these potential research designs, you’d be forgiven for feeling a little overwhelmed and wondering, “ But how do I decide which research design to use? ”. While we could write an entire post covering that alone, here are a few factors to consider that will help you choose a suitable research design for your study.

Data type: The first determining factor is naturally the type of data you plan to be collecting – i.e., qualitative or quantitative. This may sound obvious, but we have to be clear about this – don’t try to use a quantitative research design on qualitative data (or vice versa)!

Research aim(s) and question(s): As with all methodological decisions, your research aim and research questions will heavily influence your research design. For example, if your research aims involve developing a theory from qualitative data, grounded theory would be a strong option. Similarly, if your research aims involve identifying and measuring relationships between variables, one of the experimental designs would likely be a better option.

Time: It’s essential that you consider any time constraints you have, as this will impact the type of research design you can choose. For example, if you’ve only got a month to complete your project, a lengthy design such as ethnography wouldn’t be a good fit.

Resources: Take into account the resources realistically available to you, as these need to factor into your research design choice. For example, if you require highly specialised lab equipment to execute an experimental design, you need to be sure that you’ll have access to that before you make a decision.

Keep in mind that when it comes to research, it’s important to manage your risks and play as conservatively as possible. If your entire project relies on you achieving a huge sample, having access to niche equipment or holding interviews with very difficult-to-reach participants, you’re creating risks that could kill your project. So, be sure to think through your choices carefully and make sure that you have backup plans for any existential risks. Remember that a relatively simple methodology executed well generally will typically earn better marks than a highly-complex methodology executed poorly.

Recap: Key Takeaways

We’ve covered a lot of ground here. Let’s recap by looking at the key takeaways:

- Research design refers to the overall plan, structure or strategy that guides a research project, from its conception to the final analysis of data.

- Research designs for quantitative studies include descriptive , correlational , experimental and quasi-experimenta l designs.

- Research designs for qualitative studies include phenomenological , grounded theory , ethnographic and case study designs.

- When choosing a research design, you need to consider a variety of factors, including the type of data you’ll be working with, your research aims and questions, your time and the resources available to you.

If you need a helping hand with your research design (or any other aspect of your research), check out our private coaching services .

Learn More About Methodology

Triangulation: The Ultimate Credibility Enhancer

Triangulation is one of the best ways to enhance the credibility of your research. Learn about the different options here.

Research Limitations 101: What You Need To Know

Learn everything you need to know about research limitations (AKA limitations of the study). Includes practical examples from real studies.

In Vivo Coding 101: Full Explainer With Examples

Learn about in vivo coding, a popular qualitative coding technique ideal for studies where the nuances of language are central to the aims.

Process Coding 101: Full Explainer With Examples

Learn about process coding, a popular qualitative coding technique ideal for studies exploring processes, actions and changes over time.

Qualitative Coding 101: Inductive, Deductive & Hybrid Coding

Inductive, Deductive & Abductive Coding Qualitative Coding Approaches Explained...

📄 FREE TEMPLATES

Research Topic Ideation

Proposal Writing

Literature Review

Methodology & Analysis

Academic Writing

Referencing & Citing

Apps, Tools & Tricks

The Grad Coach Podcast

15 Comments

Is there any blog article explaining more on Case study research design? Is there a Case study write-up template? Thank you.

Thanks this was quite valuable to clarify such an important concept.

Thanks for this simplified explanations. it is quite very helpful.

This was really helpful. thanks

Thank you for your explanation. I think case study research design and the use of secondary data in researches needs to be talked about more in your videos and articles because there a lot of case studies research design tailored projects out there.

Please is there any template for a case study research design whose data type is a secondary data on your repository?

This post is very clear, comprehensive and has been very helpful to me. It has cleared the confusion I had in regard to research design and methodology.

This post is helpful, easy to understand, and deconstructs what a research design is. Thanks

This post is really helpful.

how to cite this page

Thank you very much for the post. It is wonderful and has cleared many worries in my mind regarding research designs. I really appreciate .

how can I put this blog as my reference(APA style) in bibliography part?

This post has been very useful to me. Confusing areas have been cleared

This is very helpful and very useful!

Wow! This post has an awful explanation. Appreciated.

Thanks This has been helpful

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Submit Comment

- Print Friendly

- Product overview

- All features

- Latest feature release

- App integrations

- project icon Project management

- Project views

- Custom fields

- Status updates

- goal icon Goals and reporting

- Reporting dashboards

- asana-intelligence icon Asana AI

- workflow icon Workflows and automation

- portfolio icon Resource management

- Capacity planning

- Time tracking

- my-task icon Admin and security

- Admin console

- Permissions

- list icon Personal

- premium icon Starter

- briefcase icon Advanced

- Goal management

- Organizational planning

- Project intake

- Resource planning

- Product launches

- View all uses arrow-right icon

- Work management resources Discover best practices, watch webinars, get insights

- Customer stories See how the world's best organizations drive work innovation with Asana

- Help Center Get lots of tips, tricks, and advice to get the most from Asana

- Asana Academy Sign up for interactive courses and webinars to learn Asana

- Developers Learn more about building apps on the Asana platform

- Community programs Connect with and learn from Asana customers around the world

- Events Find out about upcoming events near you

- Partners Learn more about our partner programs

- Asana for nonprofits Get more information on our nonprofit discount program, and apply.

- Project plans

- Team goals & objectives

- Team continuity

- Meeting agenda

- View all templates arrow-right icon

- Project planning |

- What is project design? 7 steps with ex ...

What is project design? 7 steps with expert tips

Project design is an early phase of the project lifecycle where ideas, processes, resources, and deliverables are planned out in seven steps. With detailed resources and visual elements, find out how project design can streamline your team’s efficiency.

When it comes to managing projects, it can be hard to get everyone on the same page. With multiple moving parts, different deliverables, and cross-departmental collaboration, sometimes an initial project meeting just isn’t enough.

We’ll go over the basics of project design, lay out the seven steps to create a project design, and provide expert tips to help you better understand the process.

How project design works

Project design is an early phase of the project lifecycle where ideas, processes, resources, and deliverables are planned out. A project design comes before a project plan as it’s a broad overview whereas a project plan includes more detailed information.

There are seven steps involved when creating a project design, including defining goals and using a visual aid to communicate objectives.

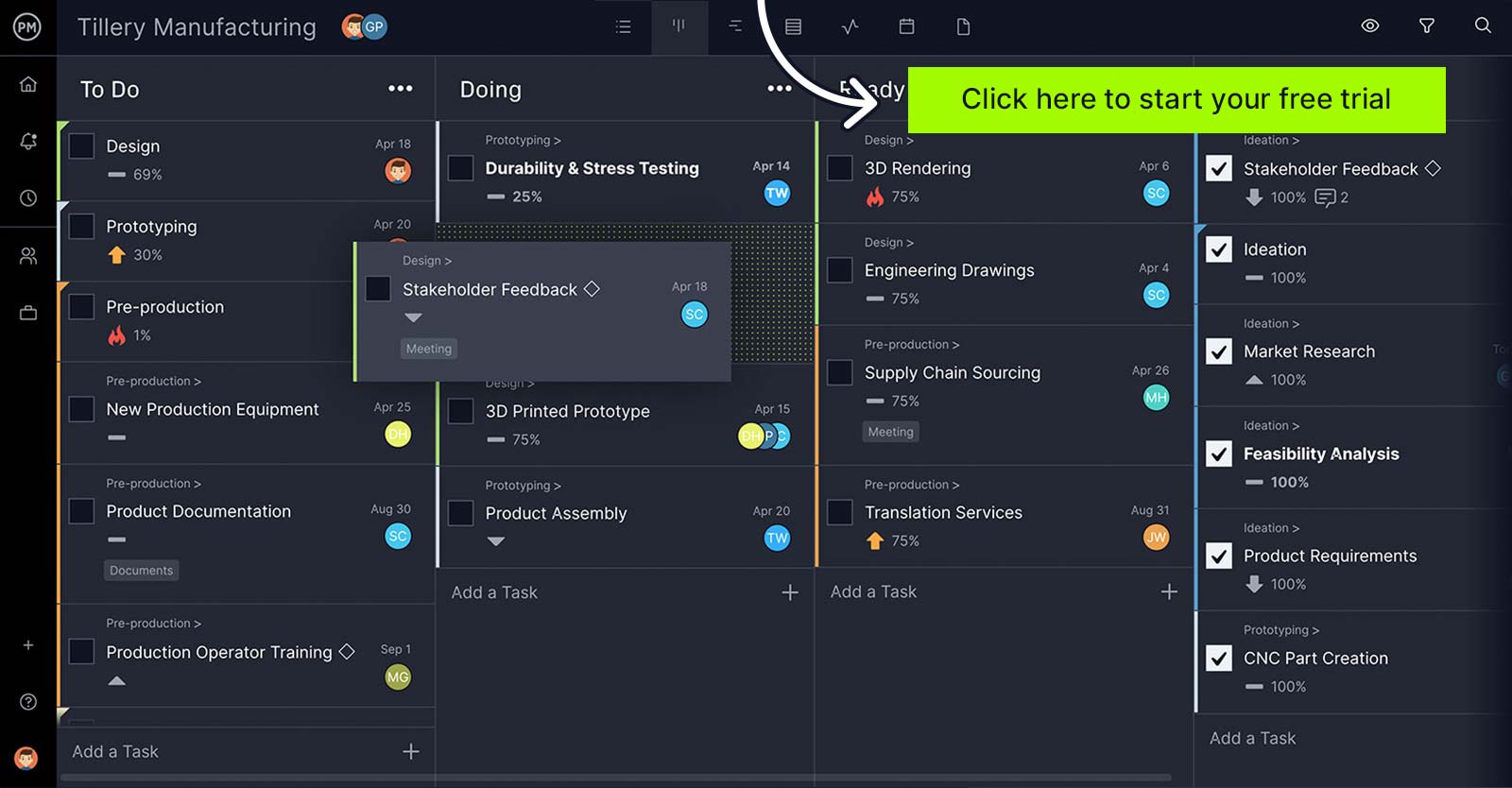

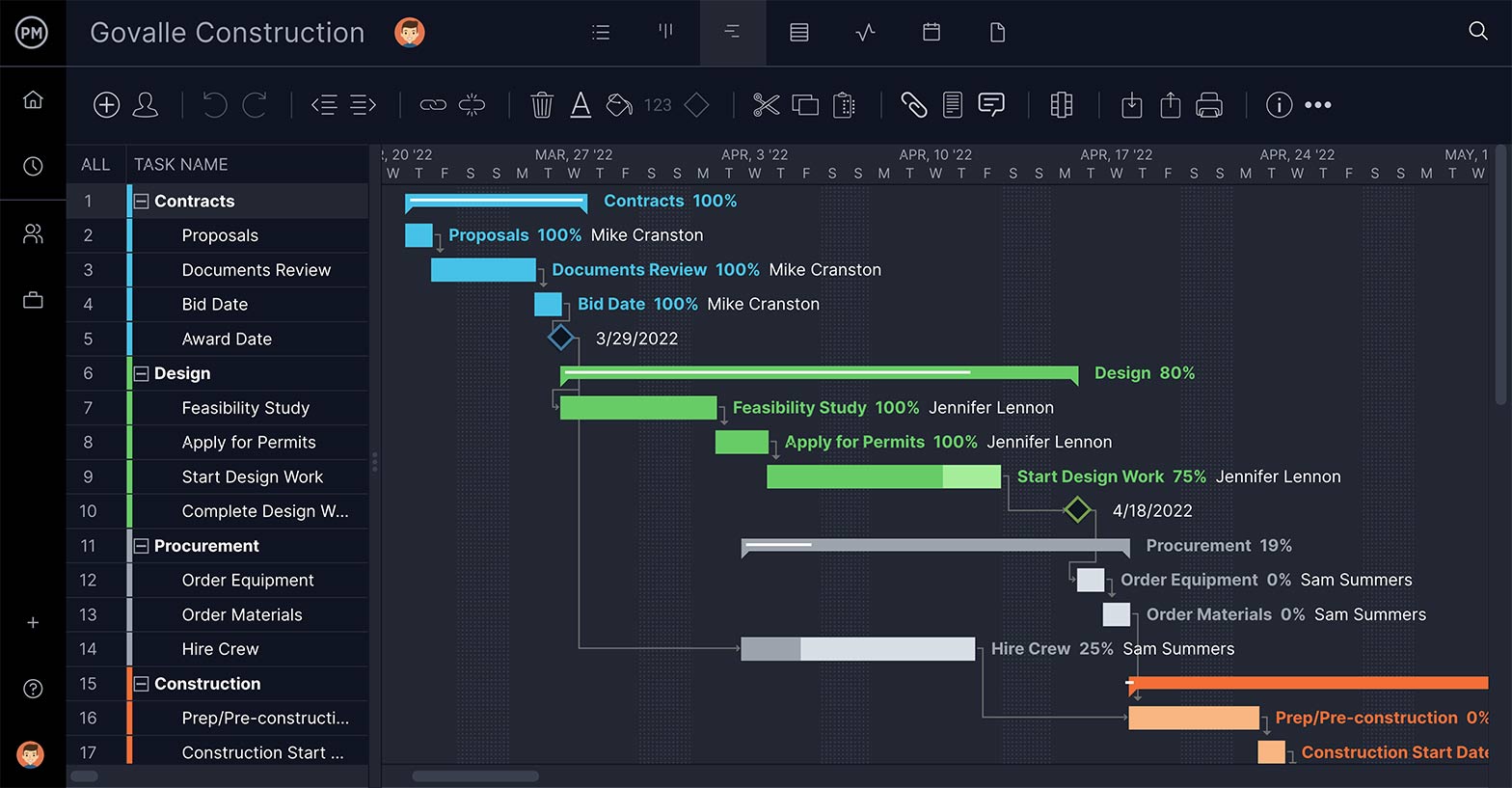

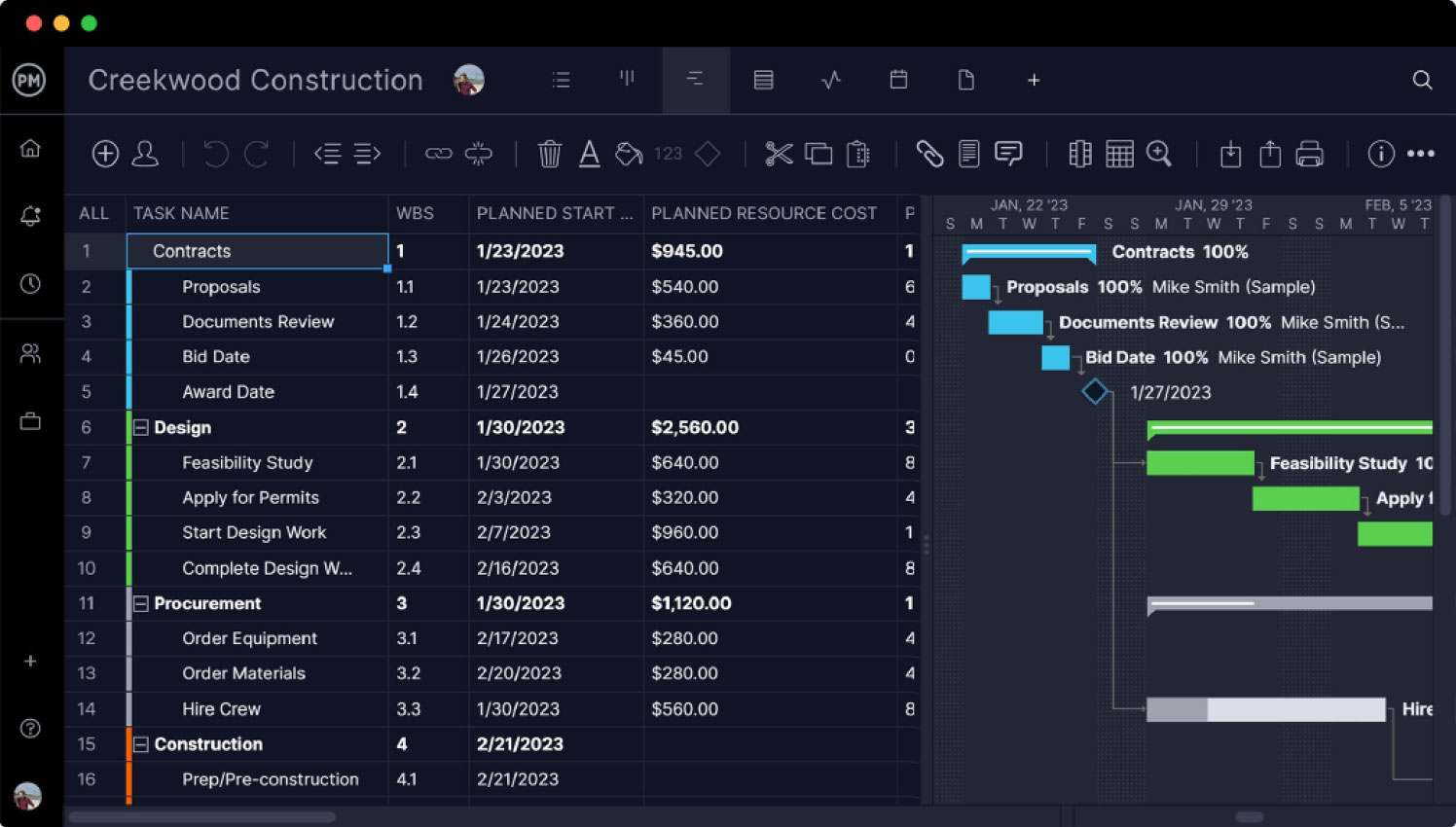

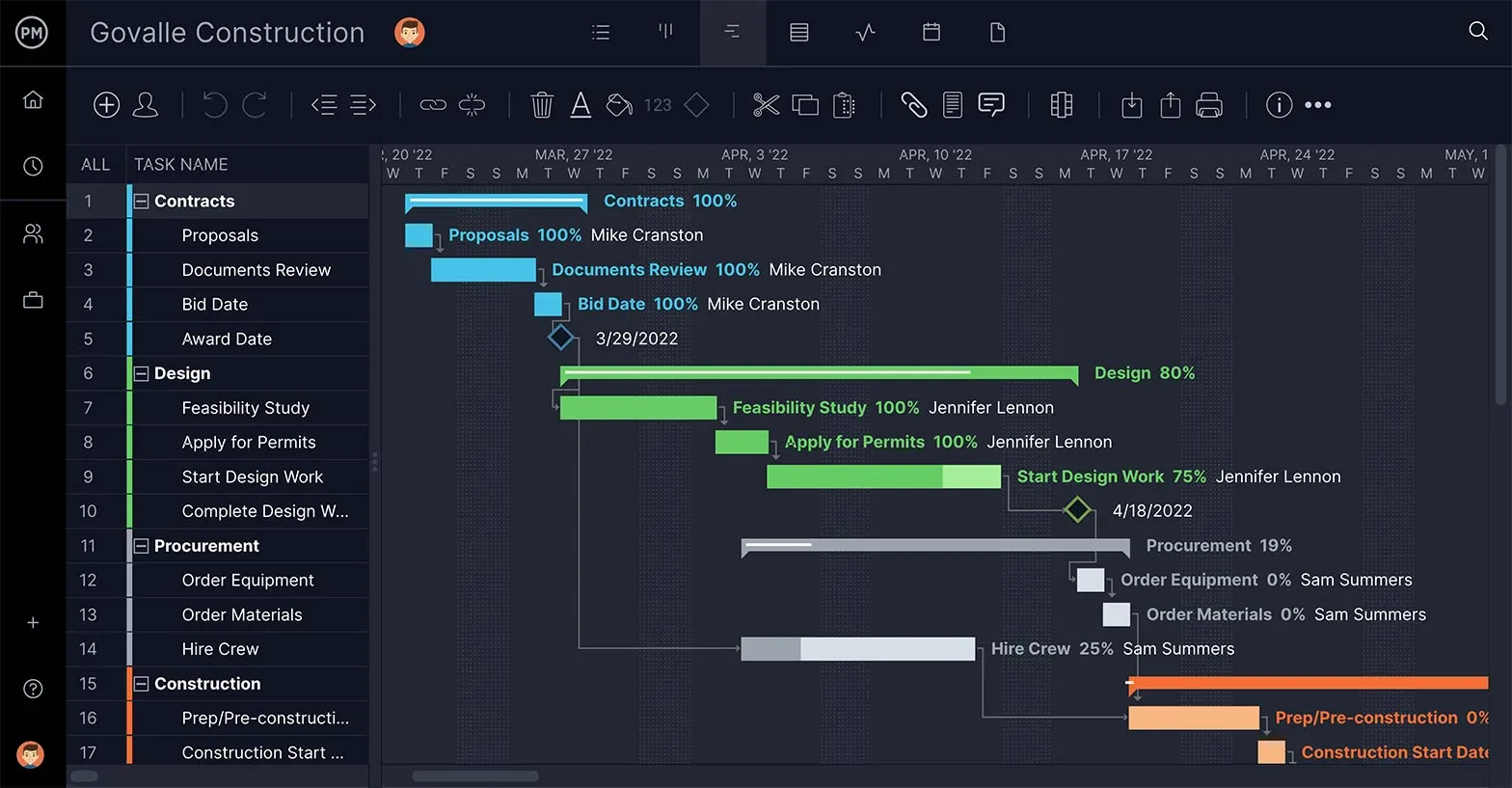

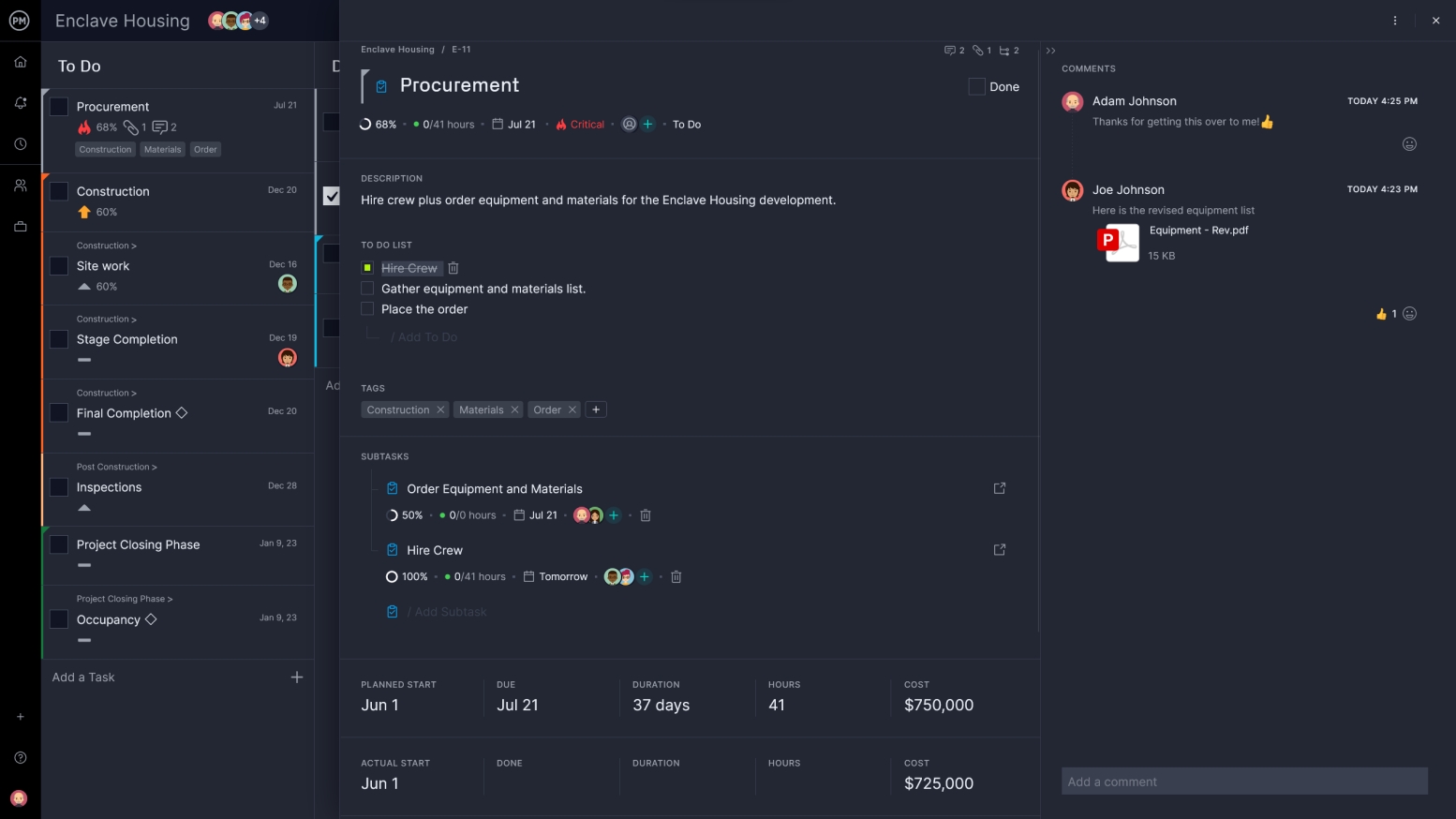

These visual elements include a variety of methods such as Gantt charts, Kanban boards, and flowcharts. Providing a visual representation of your project strategy can help create transparency between stakeholders and clarify different aspects of the project, including its overall feasibility.

The 7 steps of project design

There are seven steps that make up a successful project design process. These include everything from defining goals and baseline objectives to strengthening your strategy to help you stay organized while managing a new project.

Let’s go over each of the steps needed to create a project design.

Step 1. Define project goals

In the first step, define your project goals. To begin, lead an initial ideation meeting where you document the general project timeline and deliverables.

To start, consider the needs of the project and stakeholders. What is it you’re trying to solve? Begin writing a short description of the project and who is involved.

Once you’ve outlined the basic goals of the project, determine the more concrete objectives in detail.

Pro tip: Use SMART goals when starting your project design to better visualize where you’re going. SMART is an acronym that stands for s pecific, m easurable, a chievable, r ealistic, and t ime-bound.

Step 2. Determine outcomes

Next, narrow down the outcomes of the project. These are usually more detailed than the initial goal planning phase and include the specific tasks you will complete during the project.

For example, imagine you’re working on a project to add a new landing page to your website. One of your outcomes may be to add an email signup form.

Document the outcomes and major deliverables needed alongside the project goals to begin building a timeframe. It’s a good idea to reference popular project management methodologies to decide which one fits the needs of your project.

Pro tip: For complex projects, use the Agile methodology with iterations to break large tasks into short sprints. For more traditional projects, use the waterfall method which provides a thorough step-by-step approach.

Step 3. Identify risks and constraints

Once you’ve identified the outcomes, consider your project risks and constraints. Evaluate the aspects of your project that could lead to risk in order to prevent wasted resources down the line.

In order to identify risks and constraints, determine the resource management tools, funds, and timeframe needed. Work to resolve these constraints before the project begins by following up with relevant stakeholders and project teams.

Pro tip: Use a risk register to analyze, document, and solve project risks that arise.

Step 4. Refine your project strategy with a visual aid

A project strategy is a visual roadmap of your project . This helps communicate purpose to team members. Create your strategy by choosing a visual aid that you can share with stakeholders.

There are many types of visual aids you can choose from, some of which include:

Flowchart: A flowchart is a visual representation of the steps and decisions needed to perform a process. Flowcharts are particularly helpful ways to visualize step-by-step approaches and effectively organize project deliverables.

Gantt chart: A Gantt chart is a horizontal bar chart used to illustrate a timeline of a project. The bars in a Gantt chart represent the steps in the project and the length of the bars represent the amount of time they will take to be completed.

Work breakdown structure (WBS): A WBS is the breakdown of all tasks within a given project. Project managers use work breakdown structures to help teams visualize deliverables while keeping objectives top of mind.

Mind map: A mind map is a hierarchy diagram used to visualize projects and tasks. It allows project managers to link deliverables around a central concept or idea such as a specific team goal.

PERT chart: A PERT chart or diagram is a tool used to schedule, organize, and map out tasks. It can be helpful for complex projects and estimating the time needed to complete tasks.

Since each visual tool differs slightly, the aid you choose is up to your team preferences. While a work breakdown structure that details dependencies works well for large teams, a flowchart works well for smaller teams with less complex projects.

Pro tip: Examine the features of components of each of the visual aids before adding one to your project design. You can do this by reviewing each based on the amount of detail included, usability, and visual appearance. This way you can find the one that best fits your needs.

Step 5. Estimate your budget

Next, estimate your project budget to begin resource allocation . Your budget will incorporate the project’s profitability, resources available, and outsourced work needed. It may also be a set number determined by leadership that you’ll need to work around when it comes to being able to execute each deliverable.

Your budget may need to be approved or revised based on leadership signoff. Once finalized, you can begin assigning beneficiaries, design documents, and tasks for your project.

Pro tip: When it comes to resource allocation, implementing automated processes with automation software can improve efficiency and reduce project errors.

Step 6. Create a contingency plan

To begin assigning tasks, create a contingency plan. A contingency plan is a backup plan for the risks and constraints outlined earlier in the process. Having an organized plan when issues arise helps to resolve them in real time and streamline efficiency.

To create one, organize your risks using a Gantt chart or timeline tool and determine a plan for each risk. For example, if one of your risks involves materials not arriving in time, your contingency plan may be to source materials from elsewhere or start on a different part of the project while waiting for materials.

Once you’ve outlined a plan for each risk, you’re ready to begin executing your project.

Pro tip: Use Asana to view lists, timelines, and Gantt charts to better visualize your project plan .

Step 7. Document your milestones

For the final step, document your team’s milestones. This is done to ensure work is being completed on time and to easily identify inconsistencies as they arise.

You can do this using project management software where stakeholders can access the information and progress. It’s a good idea to manage these milestones until the end of the project to ensure tasks are completed on time.

Pro tip: Connect with project stakeholders frequently to keep track of task dependencies and ensure short term goals are met.

3 expert tips to improve your project design

Building a project design that improves collaboration and empowers efficiency is no easy task. Along with the seven steps that make up the project design process, here are a few tips that can take your design one step further.

Keep these three tips in mind when building a project design of your own:

Communicate with stakeholders early and often: Communication is key no matter the project you’re working on. Collaborating early on in the project can ensure all stakeholders are on the same page and understand the most important objectives. You can do this by leading meetings through the entirety of the project and using workflows to streamline teamwork.

Keep your goals top of mind: Connecting your goals to project deliverables can ensure objectives are being met every step of the way. You can do this with the help of timeline software where you can easily connect goals with the work needed to complete them.

Use visual elements to track milestones: While a business case and daily to-dos are helpful, visual elements help stakeholders see the bigger picture. From Gantt charts to PERT charts, there are a number of ways to visualize your project work.

Beyond these three tips, always keep your team’s best interests in mind. Providing the necessary information and scheduling work within reasonable deadlines will keep your team engaged and efficient.

Use project design to tell a story

Project design is an important piece of executing a successful project. From gathering the necessary information and resources to coordinating with team members, your job is to bring the details to life. With the right project design, you and your team can tackle anything that comes your way.

Take the art of project planning one step further with work management software. From streamlining work to improving visibility, Asana can help your team achieve more with clarity and confidence.

Related resources

7 steps to crafting a winning event proposal (with template)

How Asana drives impactful product launches in 3 steps

How to streamline compliance management software with Asana

New site openings: How to reduce costs and delays

What is Research Design? Characteristics, Types, Process, & Examples

Link Copied

Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Share on LinkedIn

Your search has come to an end!

Ever felt like a hamster on a research wheel fast, spinning with a million questions but going nowhere? You've got your topic; you're brimming with curiosity, but... what next? So, forget the research rut and get your papers! This ultimate guide to "what is research design?" will have you navigating your project like a pro, uncovering answers and avoiding dead ends. Know the features of good research design, what you mean by research design, elements of research design, and more.

What is Research Design?

Before starting with the topic, do you know what is research design? Research design is the structure of research methods and techniques selected to conduct a study. It refines the methods suited to the subject and ensures a successful setup. Defining a research topic clarifies the type of research (experimental, survey research, correlational, semi-experimental, review) and its sub-type (experimental design, research problem, descriptive case-study).

There are three main types of designs for research:

1. Data Collection

2. Measurement

3. Data Analysis

Elements of Research Design

Now that you know what is research design, it is important to know the elements and components of research design. Impactful research minimises bias and enhances data accuracy. Designs with minimal error margins are ideal. Key elements include:

1. Accurate purpose statement

2. Techniques for data collection and analysis

3. Methods for data analysis

4. Type of research methodology

5. Probable objections to research

6. Research settings

7. Timeline

8. Measurement of analysis

Got a hang of research, now book yout student accommodation with one click!

Book through amber today!

Characteristics of Research Design

Research design has several key characteristics that contribute to the validity, reliability, and overall success of a research study. To know the answer for what is research design, it is important to know the characteristics. These are-

1. Reliability

A reliable research design ensures that each study’s results are accurate and can be replicated. This means that if the research is conducted again under the same conditions, it should yield similar results.

2. Validity

A valid research design uses appropriate measuring tools to gauge the results according to the research objective. This ensures that the data collected and the conclusions drawn are relevant and accurately reflect the phenomenon being studied.

3. Neutrality

A neutral research design ensures that the assumptions made at the beginning of the research are free from bias. This means that the data collected throughout the research is based on these unbiased assumptions.

4. Generalizability

A good research design draws an outcome that can be applied to a large set of people and is not limited to the sample size or the research group.

Research Design Process

What is research design? A good research helps you do a really good study that gives fair, trustworthy, and useful results. But it's also good to have a bit of wiggle room for changes. If you’re wondering how to conduct a research in just 5 mins , here's a breakdown and examples to work even better.

1. Consider Aims and Approaches

Define the research questions and objectives, and establish the theoretical framework and methodology.

2. Choose a Type of Research Design

Select the suitable research design, such as experimental, correlational, survey, case study, or ethnographic, according to the research questions and objectives.

3. Identify Population and Sampling Method

Determine the target population and sample size, and select the sampling method, like random, stratified random sampling, or convenience sampling.

4. Choose Data Collection Methods

Decide on the data collection methods, such as surveys, interviews, observations, or experiments, and choose the appropriate instruments for data collection.

5. Plan Data Collection Procedures

Create a plan for data collection, detailing the timeframe, location, and personnel involved, while ensuring ethical considerations are met.

6. Decide on Data Analysis Strategies

Select the appropriate data analysis techniques, like statistical analysis, content analysis, or discourse analysis, and plan the interpretation of the results.

What are the Types of Research Design?

A researcher must grasp various types to decide which model to use for a study. There are different research designs that can be broadly classified into quantitative and qualitative.

Qualitative Research

Qualitative research identifies relationships between collected data and observations through mathematical calculations. Statistical methods validate or refute theories about natural phenomena. This research method answers "why" a theory exists and explores respondents' perspectives.

Quantitative Research

Quantitative research is essential when statistical conclusions are needed to gather actionable insights. Numbers provide clarity for critical business decisions. This method is crucial for organizational growth, with insights from complex numerical data guiding future business decisions.

Qualitative Research vs Quantitative Research

While researching, it is important to know the difference between qualitative and quantitative research. Here's a quick difference between the two:

| Aspect | Qualitative Research | Quantitative Research |

|---|---|---|

| Data Type | Non-numerical data such as words, images, and sounds. | Numerical data that can be measured and expressed in numerical terms. |

| Purpose | To understand concepts, thoughts, or experiences. | To test hypotheses, identify patterns, and make predictions. |

| Data Collection | Common methods include interviews with open-ended questions, observations described in words, and literature reviews. | Common methods include surveys with closed-ended questions, experiments, and observations recorded as numbers. |

| Data Analysis | Data is analyzed using grounded theory or thematic analysis. | Data is analyzed using statistical methods. |

| Outcome | Produces rich and detailed descriptions of the phenomenon being studied, and uncovers new insights and meanings. | Produces objective, empirical data that can be measured. |

The research types can be further divided into 5 categories:

1. Descriptive Research

Descriptive research design focuses on detailing a situation or case. It's a theory-driven method that involves gathering, analysing, and presenting data. This approach offers insights into the reasons and mechanisms behind a research subject, enhancing understanding of the research's importance. When the problem statement is unclear, exploratory research can be conducted.

2. Experimental Research

Experimental research design investigates cause-and-effect relationships. It’s a causal design where the impact of an independent variable on a dependent variable is observed. For example, the effect of price on customer satisfaction. This method efficiently addresses problems by manipulating independent variables to see their effect on dependent variables. Often used in social sciences, it involves analysing human behaviour by studying changes in one group's actions and their impact on another group.

3. Correlational Research

Correlational research design is a non-experimental technique that identifies relationships between closely linked variables. It uses statistical analysis to determine these relationships without assumptions. This method requires two different groups. A correlation coefficient between -1 and +1 indicates the strength and direction of the relationship, with +1 showing a positive correlation and -1 a negative correlation.

4. Diagnostic Research

Diagnostic research design aims to identify the underlying causes of specific issues. This method delves into factors creating problematic situations and has three phases:

- Issue inception

- Issue diagnosis

- Issue resolution

5. Explanatory Research

Explanatory research design builds on a researcher’s ideas to explore theories further. It seeks to explain the unexplored aspects of a subject, addressing the what, how, and why of research questions.

Benefits of Research Design

After learning about what is research design and the process, it is important to know the key benefits of a well-structured research design:

1. Minimises Risk of Errors: A good research design minimises the risk of errors and reduces inaccuracy. It ensures that the study is carried out in the right direction and that all the team members are on the same page.

2. Efficient Use of Resources: It facilitates a concrete research plan for the efficient use of time and resources. It helps the researcher better complete all the tasks, even with limited resources.

3. Provides Direction: The purpose of the research design is to enable the researcher to proceed in the right direction without deviating from the tasks. It helps to identify the major and minor tasks of the study.

4. Ensures Validity and Reliability: A well-designed research enhances the validity and reliability of the findings and allows for the replication of studies by other researchers. The main advantage of a good research design is that it provides accuracy, reliability, consistency, and legitimacy to the research.

5. Facilitates Problem-Solving: A researcher can easily frame the objectives of the research work based on the design of experiments (research design). A good research design helps the researcher find the best solution for the research problems.

6. Better Documentation: It helps in better documentation of the various activities while the project work is going on.

That's it! You've explored all the answers for what is research design in research? Remember, it's not just about picking a fancy method – it's about choosing the perfect tool to answer your burning questions. By carefully considering your goals and resources, you can design a research plan that gathers reliable information and helps you reach clear conclusions.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the key components of a research design, how can i choose the best research design for my study, what are some common pitfalls in research design, and how can they be avoided, how does research design impact the validity and reliability of a study, what ethical considerations should be taken into account in research design.

Your ideal student home & a flight ticket awaits

Follow us on :

Related Posts

What Are The Ivy League Schools?

10 Best Healthcare Courses in the UK: Your Path to a Rewarding Career!

.jpg)

Top Colleges in London To Study In 2024

amber © 2024. All rights reserved.

4.8/5 on Trustpilot

Rated as "Excellent" • 4800+ Reviews by students

Rated as "Excellent" • 4800+ Reviews by Students

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Project – Definition, Writing Guide and Ideas

Research Project – Definition, Writing Guide and Ideas

Table of Contents

Research Project

Definition :

Research Project is a planned and systematic investigation into a specific area of interest or problem, with the goal of generating new knowledge, insights, or solutions. It typically involves identifying a research question or hypothesis, designing a study to test it, collecting and analyzing data, and drawing conclusions based on the findings.

Types of Research Project

Types of Research Projects are as follows:

Basic Research

This type of research focuses on advancing knowledge and understanding of a subject area or phenomenon, without any specific application or practical use in mind. The primary goal is to expand scientific or theoretical knowledge in a particular field.

Applied Research

Applied research is aimed at solving practical problems or addressing specific issues. This type of research seeks to develop solutions or improve existing products, services or processes.

Action Research

Action research is conducted by practitioners and aimed at solving specific problems or improving practices in a particular context. It involves collaboration between researchers and practitioners, and often involves iterative cycles of data collection and analysis, with the goal of improving practices.

Quantitative Research

This type of research uses numerical data to investigate relationships between variables or to test hypotheses. It typically involves large-scale data collection through surveys, experiments, or secondary data analysis.

Qualitative Research

Qualitative research focuses on understanding and interpreting phenomena from the perspective of the people involved. It involves collecting and analyzing data in the form of text, images, or other non-numerical forms.

Mixed Methods Research

Mixed methods research combines elements of both quantitative and qualitative research, using multiple data sources and methods to gain a more comprehensive understanding of a phenomenon.

Longitudinal Research

This type of research involves studying a group of individuals or phenomena over an extended period of time, often years or decades. It is useful for understanding changes and developments over time.

Case Study Research

Case study research involves in-depth investigation of a particular case or phenomenon, often within a specific context. It is useful for understanding complex phenomena in their real-life settings.

Participatory Research

Participatory research involves active involvement of the people or communities being studied in the research process. It emphasizes collaboration, empowerment, and the co-production of knowledge.

Research Project Methodology

Research Project Methodology refers to the process of conducting research in an organized and systematic manner to answer a specific research question or to test a hypothesis. A well-designed research project methodology ensures that the research is rigorous, valid, and reliable, and that the findings are meaningful and can be used to inform decision-making.

There are several steps involved in research project methodology, which are described below:

Define the Research Question

The first step in any research project is to clearly define the research question or problem. This involves identifying the purpose of the research, the scope of the research, and the key variables that will be studied.

Develop a Research Plan

Once the research question has been defined, the next step is to develop a research plan. This plan outlines the methodology that will be used to collect and analyze data, including the research design, sampling strategy, data collection methods, and data analysis techniques.

Collect Data

The data collection phase involves gathering information through various methods, such as surveys, interviews, observations, experiments, or secondary data analysis. The data collected should be relevant to the research question and should be of sufficient quantity and quality to enable meaningful analysis.

Analyze Data

Once the data has been collected, it is analyzed using appropriate statistical techniques or other methods. The analysis should be guided by the research question and should aim to identify patterns, trends, relationships, or other insights that can inform the research findings.

Interpret and Report Findings

The final step in the research project methodology is to interpret the findings and report them in a clear and concise manner. This involves summarizing the results, discussing their implications, and drawing conclusions that can be used to inform decision-making.

Research Project Writing Guide

Here are some guidelines to help you in writing a successful research project:

- Choose a topic: Choose a topic that you are interested in and that is relevant to your field of study. It is important to choose a topic that is specific and focused enough to allow for in-depth research and analysis.

- Conduct a literature review : Conduct a thorough review of the existing research on your topic. This will help you to identify gaps in the literature and to develop a research question or hypothesis.

- Develop a research question or hypothesis : Based on your literature review, develop a clear research question or hypothesis that you will investigate in your study.

- Design your study: Choose an appropriate research design and methodology to answer your research question or test your hypothesis. This may include choosing a sample, selecting measures or instruments, and determining data collection methods.

- Collect data: Collect data using your chosen methods and instruments. Be sure to follow ethical guidelines and obtain informed consent from participants if necessary.

- Analyze data: Analyze your data using appropriate statistical or qualitative methods. Be sure to clearly report your findings and provide interpretations based on your research question or hypothesis.

- Discuss your findings : Discuss your findings in the context of the existing literature and your research question or hypothesis. Identify any limitations or implications of your study and suggest directions for future research.

- Write your project: Write your research project in a clear and organized manner, following the appropriate format and style guidelines for your field of study. Be sure to include an introduction, literature review, methodology, results, discussion, and conclusion.

- Revise and edit: Revise and edit your project for clarity, coherence, and accuracy. Be sure to proofread for spelling, grammar, and formatting errors.

- Cite your sources: Cite your sources accurately and appropriately using the appropriate citation style for your field of study.

Examples of Research Projects

Some Examples of Research Projects are as follows:

- Investigating the effects of a new medication on patients with a particular disease or condition.

- Exploring the impact of exercise on mental health and well-being.

- Studying the effectiveness of a new teaching method in improving student learning outcomes.

- Examining the impact of social media on political participation and engagement.

- Investigating the efficacy of a new therapy for a specific mental health disorder.

- Exploring the use of renewable energy sources in reducing carbon emissions and mitigating climate change.

- Studying the effects of a new agricultural technique on crop yields and environmental sustainability.

- Investigating the effectiveness of a new technology in improving business productivity and efficiency.

- Examining the impact of a new public policy on social inequality and access to resources.

- Exploring the factors that influence consumer behavior in a specific market.

Characteristics of Research Project

Here are some of the characteristics that are often associated with research projects:

- Clear objective: A research project is designed to answer a specific question or solve a particular problem. The objective of the research should be clearly defined from the outset.

- Systematic approach: A research project is typically carried out using a structured and systematic approach that involves careful planning, data collection, analysis, and interpretation.

- Rigorous methodology: A research project should employ a rigorous methodology that is appropriate for the research question being investigated. This may involve the use of statistical analysis, surveys, experiments, or other methods.

- Data collection : A research project involves collecting data from a variety of sources, including primary sources (such as surveys or experiments) and secondary sources (such as published literature or databases).

- Analysis and interpretation : Once the data has been collected, it needs to be analyzed and interpreted. This involves using statistical techniques or other methods to identify patterns or relationships in the data.

- Conclusion and implications : A research project should lead to a clear conclusion that answers the research question. It should also identify the implications of the findings for future research or practice.

- Communication: The results of the research project should be communicated clearly and effectively, using appropriate language and visual aids, to a range of audiences, including peers, stakeholders, and the wider public.

Importance of Research Project

Research projects are an essential part of the process of generating new knowledge and advancing our understanding of various fields of study. Here are some of the key reasons why research projects are important:

- Advancing knowledge : Research projects are designed to generate new knowledge and insights into particular topics or questions. This knowledge can be used to inform policies, practices, and decision-making processes across a range of fields.

- Solving problems: Research projects can help to identify solutions to real-world problems by providing a better understanding of the causes and effects of particular issues.

- Developing new technologies: Research projects can lead to the development of new technologies or products that can improve people’s lives or address societal challenges.

- Improving health outcomes: Research projects can contribute to improving health outcomes by identifying new treatments, diagnostic tools, or preventive strategies.

- Enhancing education: Research projects can enhance education by providing new insights into teaching and learning methods, curriculum development, and student learning outcomes.

- Informing public policy : Research projects can inform public policy by providing evidence-based recommendations and guidance on issues related to health, education, environment, social justice, and other areas.

- Enhancing professional development : Research projects can enhance the professional development of researchers by providing opportunities to develop new skills, collaborate with colleagues, and share knowledge with others.

Research Project Ideas

Following are some Research Project Ideas:

Field: Psychology

- Investigating the impact of social support on coping strategies among individuals with chronic illnesses.

- Exploring the relationship between childhood trauma and adult attachment styles.

- Examining the effects of exercise on cognitive function and brain health in older adults.

- Investigating the impact of sleep deprivation on decision making and risk-taking behavior.

- Exploring the relationship between personality traits and leadership styles in the workplace.

- Examining the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for treating anxiety disorders.

- Investigating the relationship between social comparison and body dissatisfaction in young women.

- Exploring the impact of parenting styles on children’s emotional regulation and behavior.

- Investigating the effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions for treating depression.

- Examining the relationship between childhood adversity and later-life health outcomes.

Field: Economics

- Analyzing the impact of trade agreements on economic growth in developing countries.

- Examining the effects of tax policy on income distribution and poverty reduction.

- Investigating the relationship between foreign aid and economic development in low-income countries.

- Exploring the impact of globalization on labor markets and job displacement.

- Analyzing the impact of minimum wage laws on employment and income levels.

- Investigating the effectiveness of monetary policy in managing inflation and unemployment.

- Examining the relationship between economic freedom and entrepreneurship.

- Analyzing the impact of income inequality on social mobility and economic opportunity.

- Investigating the role of education in economic development.

- Examining the effectiveness of different healthcare financing systems in promoting health equity.

Field: Sociology

- Investigating the impact of social media on political polarization and civic engagement.

- Examining the effects of neighborhood characteristics on health outcomes.

- Analyzing the impact of immigration policies on social integration and cultural diversity.

- Investigating the relationship between social support and mental health outcomes in older adults.

- Exploring the impact of income inequality on social cohesion and trust.

- Analyzing the effects of gender and race discrimination on career advancement and pay equity.

- Investigating the relationship between social networks and health behaviors.

- Examining the effectiveness of community-based interventions for reducing crime and violence.

- Analyzing the impact of social class on cultural consumption and taste.

- Investigating the relationship between religious affiliation and social attitudes.

Field: Computer Science

- Developing an algorithm for detecting fake news on social media.

- Investigating the effectiveness of different machine learning algorithms for image recognition.

- Developing a natural language processing tool for sentiment analysis of customer reviews.

- Analyzing the security implications of blockchain technology for online transactions.

- Investigating the effectiveness of different recommendation algorithms for personalized advertising.

- Developing an artificial intelligence chatbot for mental health counseling.

- Investigating the effectiveness of different algorithms for optimizing online advertising campaigns.

- Developing a machine learning model for predicting consumer behavior in online marketplaces.

- Analyzing the privacy implications of different data sharing policies for online platforms.

- Investigating the effectiveness of different algorithms for predicting stock market trends.

Field: Education

- Investigating the impact of teacher-student relationships on academic achievement.

- Analyzing the effectiveness of different pedagogical approaches for promoting student engagement and motivation.

- Examining the effects of school choice policies on academic achievement and social mobility.

- Investigating the impact of technology on learning outcomes and academic achievement.

- Analyzing the effects of school funding disparities on educational equity and achievement gaps.

- Investigating the relationship between school climate and student mental health outcomes.

- Examining the effectiveness of different teaching strategies for promoting critical thinking and problem-solving skills.

- Investigating the impact of social-emotional learning programs on student behavior and academic achievement.

- Analyzing the effects of standardized testing on student motivation and academic achievement.

Field: Environmental Science

- Investigating the impact of climate change on species distribution and biodiversity.

- Analyzing the effectiveness of different renewable energy technologies in reducing carbon emissions.

- Examining the impact of air pollution on human health outcomes.

- Investigating the relationship between urbanization and deforestation in developing countries.

- Analyzing the effects of ocean acidification on marine ecosystems and biodiversity.

- Investigating the impact of land use change on soil fertility and ecosystem services.

- Analyzing the effectiveness of different conservation policies and programs for protecting endangered species and habitats.

- Investigating the relationship between climate change and water resources in arid regions.

- Examining the impact of plastic pollution on marine ecosystems and biodiversity.

- Investigating the effects of different agricultural practices on soil health and nutrient cycling.

Field: Linguistics

- Analyzing the impact of language diversity on social integration and cultural identity.

- Investigating the relationship between language and cognition in bilingual individuals.

- Examining the effects of language contact and language change on linguistic diversity.

- Investigating the role of language in shaping cultural norms and values.

- Analyzing the effectiveness of different language teaching methodologies for second language acquisition.

- Investigating the relationship between language proficiency and academic achievement.

- Examining the impact of language policy on language use and language attitudes.

- Investigating the role of language in shaping gender and social identities.

- Analyzing the effects of dialect contact on language variation and change.

- Investigating the relationship between language and emotion expression.

Field: Political Science

- Analyzing the impact of electoral systems on women’s political representation.

- Investigating the relationship between political ideology and attitudes towards immigration.

- Examining the effects of political polarization on democratic institutions and political stability.

- Investigating the impact of social media on political participation and civic engagement.

- Analyzing the effects of authoritarianism on human rights and civil liberties.

- Investigating the relationship between public opinion and foreign policy decisions.

- Examining the impact of international organizations on global governance and cooperation.

- Investigating the effectiveness of different conflict resolution strategies in resolving ethnic and religious conflicts.

- Analyzing the effects of corruption on economic development and political stability.

- Investigating the role of international law in regulating global governance and human rights.

Field: Medicine

- Investigating the impact of lifestyle factors on chronic disease risk and prevention.

- Examining the effectiveness of different treatment approaches for mental health disorders.

- Investigating the relationship between genetics and disease susceptibility.

- Analyzing the effects of social determinants of health on health outcomes and health disparities.

- Investigating the impact of different healthcare delivery models on patient outcomes and cost effectiveness.

- Examining the effectiveness of different prevention and treatment strategies for infectious diseases.

- Investigating the relationship between healthcare provider communication skills and patient satisfaction and outcomes.

- Analyzing the effects of medical error and patient safety on healthcare quality and outcomes.

- Investigating the impact of different pharmaceutical pricing policies on access to essential medicines.

- Examining the effectiveness of different rehabilitation approaches for improving function and quality of life in individuals with disabilities.

Field: Anthropology

- Analyzing the impact of colonialism on indigenous cultures and identities.

- Investigating the relationship between cultural practices and health outcomes in different populations.

- Examining the effects of globalization on cultural diversity and cultural exchange.

- Investigating the role of language in cultural transmission and preservation.

- Analyzing the effects of cultural contact on cultural change and adaptation.

- Investigating the impact of different migration policies on immigrant integration and acculturation.

- Examining the role of gender and sexuality in cultural norms and values.

- Investigating the impact of cultural heritage preservation on tourism and economic development.

- Analyzing the effects of cultural revitalization movements on indigenous communities.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Survey Instruments – List and Their Uses

Tables in Research Paper – Types, Creating Guide...

Theoretical Framework – Types, Examples and...

Research Results Section – Writing Guide and...

Literature Review – Types Writing Guide and...

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

Published on 5 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 20 March 2023.

A research design is a strategy for answering your research question using empirical data. Creating a research design means making decisions about:

- Your overall aims and approach

- The type of research design you’ll use

- Your sampling methods or criteria for selecting subjects

- Your data collection methods

- The procedures you’ll follow to collect data

- Your data analysis methods

A well-planned research design helps ensure that your methods match your research aims and that you use the right kind of analysis for your data.

Table of contents

Step 1: consider your aims and approach, step 2: choose a type of research design, step 3: identify your population and sampling method, step 4: choose your data collection methods, step 5: plan your data collection procedures, step 6: decide on your data analysis strategies, frequently asked questions.

- Introduction

Before you can start designing your research, you should already have a clear idea of the research question you want to investigate.

There are many different ways you could go about answering this question. Your research design choices should be driven by your aims and priorities – start by thinking carefully about what you want to achieve.

The first choice you need to make is whether you’ll take a qualitative or quantitative approach.

| Qualitative approach | Quantitative approach |

|---|---|

Qualitative research designs tend to be more flexible and inductive , allowing you to adjust your approach based on what you find throughout the research process.

Quantitative research designs tend to be more fixed and deductive , with variables and hypotheses clearly defined in advance of data collection.

It’s also possible to use a mixed methods design that integrates aspects of both approaches. By combining qualitative and quantitative insights, you can gain a more complete picture of the problem you’re studying and strengthen the credibility of your conclusions.

Practical and ethical considerations when designing research

As well as scientific considerations, you need to think practically when designing your research. If your research involves people or animals, you also need to consider research ethics .

- How much time do you have to collect data and write up the research?

- Will you be able to gain access to the data you need (e.g., by travelling to a specific location or contacting specific people)?

- Do you have the necessary research skills (e.g., statistical analysis or interview techniques)?

- Will you need ethical approval ?

At each stage of the research design process, make sure that your choices are practically feasible.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Within both qualitative and quantitative approaches, there are several types of research design to choose from. Each type provides a framework for the overall shape of your research.

Types of quantitative research designs

Quantitative designs can be split into four main types. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs allow you to test cause-and-effect relationships, while descriptive and correlational designs allow you to measure variables and describe relationships between them.

| Type of design | Purpose and characteristics |

|---|---|

| Experimental | |

| Quasi-experimental | |

| Correlational | |

| Descriptive |

With descriptive and correlational designs, you can get a clear picture of characteristics, trends, and relationships as they exist in the real world. However, you can’t draw conclusions about cause and effect (because correlation doesn’t imply causation ).

Experiments are the strongest way to test cause-and-effect relationships without the risk of other variables influencing the results. However, their controlled conditions may not always reflect how things work in the real world. They’re often also more difficult and expensive to implement.

Types of qualitative research designs

Qualitative designs are less strictly defined. This approach is about gaining a rich, detailed understanding of a specific context or phenomenon, and you can often be more creative and flexible in designing your research.

The table below shows some common types of qualitative design. They often have similar approaches in terms of data collection, but focus on different aspects when analysing the data.

| Type of design | Purpose and characteristics |

|---|---|

| Grounded theory | |

| Phenomenology |

Your research design should clearly define who or what your research will focus on, and how you’ll go about choosing your participants or subjects.

In research, a population is the entire group that you want to draw conclusions about, while a sample is the smaller group of individuals you’ll actually collect data from.

Defining the population

A population can be made up of anything you want to study – plants, animals, organisations, texts, countries, etc. In the social sciences, it most often refers to a group of people.

For example, will you focus on people from a specific demographic, region, or background? Are you interested in people with a certain job or medical condition, or users of a particular product?

The more precisely you define your population, the easier it will be to gather a representative sample.

Sampling methods

Even with a narrowly defined population, it’s rarely possible to collect data from every individual. Instead, you’ll collect data from a sample.

To select a sample, there are two main approaches: probability sampling and non-probability sampling . The sampling method you use affects how confidently you can generalise your results to the population as a whole.

| Probability sampling | Non-probability sampling |

|---|---|

Probability sampling is the most statistically valid option, but it’s often difficult to achieve unless you’re dealing with a very small and accessible population.

For practical reasons, many studies use non-probability sampling, but it’s important to be aware of the limitations and carefully consider potential biases. You should always make an effort to gather a sample that’s as representative as possible of the population.

Case selection in qualitative research

In some types of qualitative designs, sampling may not be relevant.

For example, in an ethnography or a case study, your aim is to deeply understand a specific context, not to generalise to a population. Instead of sampling, you may simply aim to collect as much data as possible about the context you are studying.

In these types of design, you still have to carefully consider your choice of case or community. You should have a clear rationale for why this particular case is suitable for answering your research question.

For example, you might choose a case study that reveals an unusual or neglected aspect of your research problem, or you might choose several very similar or very different cases in order to compare them.

Data collection methods are ways of directly measuring variables and gathering information. They allow you to gain first-hand knowledge and original insights into your research problem.

You can choose just one data collection method, or use several methods in the same study.

Survey methods

Surveys allow you to collect data about opinions, behaviours, experiences, and characteristics by asking people directly. There are two main survey methods to choose from: questionnaires and interviews.

| Questionnaires | Interviews |

|---|---|

Observation methods

Observations allow you to collect data unobtrusively, observing characteristics, behaviours, or social interactions without relying on self-reporting.

Observations may be conducted in real time, taking notes as you observe, or you might make audiovisual recordings for later analysis. They can be qualitative or quantitative.

| Quantitative observation | |

|---|---|

Other methods of data collection

There are many other ways you might collect data depending on your field and topic.

| Field | Examples of data collection methods |

|---|---|

| Media & communication | Collecting a sample of texts (e.g., speeches, articles, or social media posts) for data on cultural norms and narratives |

| Psychology | Using technologies like neuroimaging, eye-tracking, or computer-based tasks to collect data on things like attention, emotional response, or reaction time |

| Education | Using tests or assignments to collect data on knowledge and skills |

| Physical sciences | Using scientific instruments to collect data on things like weight, blood pressure, or chemical composition |

If you’re not sure which methods will work best for your research design, try reading some papers in your field to see what data collection methods they used.

Secondary data

If you don’t have the time or resources to collect data from the population you’re interested in, you can also choose to use secondary data that other researchers already collected – for example, datasets from government surveys or previous studies on your topic.

With this raw data, you can do your own analysis to answer new research questions that weren’t addressed by the original study.

Using secondary data can expand the scope of your research, as you may be able to access much larger and more varied samples than you could collect yourself.

However, it also means you don’t have any control over which variables to measure or how to measure them, so the conclusions you can draw may be limited.

As well as deciding on your methods, you need to plan exactly how you’ll use these methods to collect data that’s consistent, accurate, and unbiased.

Planning systematic procedures is especially important in quantitative research, where you need to precisely define your variables and ensure your measurements are reliable and valid.

Operationalisation

Some variables, like height or age, are easily measured. But often you’ll be dealing with more abstract concepts, like satisfaction, anxiety, or competence. Operationalisation means turning these fuzzy ideas into measurable indicators.

If you’re using observations , which events or actions will you count?

If you’re using surveys , which questions will you ask and what range of responses will be offered?

You may also choose to use or adapt existing materials designed to measure the concept you’re interested in – for example, questionnaires or inventories whose reliability and validity has already been established.

Reliability and validity

Reliability means your results can be consistently reproduced , while validity means that you’re actually measuring the concept you’re interested in.

| Reliability | Validity |

|---|---|

For valid and reliable results, your measurement materials should be thoroughly researched and carefully designed. Plan your procedures to make sure you carry out the same steps in the same way for each participant.

If you’re developing a new questionnaire or other instrument to measure a specific concept, running a pilot study allows you to check its validity and reliability in advance.

Sampling procedures

As well as choosing an appropriate sampling method, you need a concrete plan for how you’ll actually contact and recruit your selected sample.

That means making decisions about things like:

- How many participants do you need for an adequate sample size?

- What inclusion and exclusion criteria will you use to identify eligible participants?

- How will you contact your sample – by mail, online, by phone, or in person?

If you’re using a probability sampling method, it’s important that everyone who is randomly selected actually participates in the study. How will you ensure a high response rate?

If you’re using a non-probability method, how will you avoid bias and ensure a representative sample?

Data management

It’s also important to create a data management plan for organising and storing your data.

Will you need to transcribe interviews or perform data entry for observations? You should anonymise and safeguard any sensitive data, and make sure it’s backed up regularly.

Keeping your data well organised will save time when it comes to analysing them. It can also help other researchers validate and add to your findings.

On their own, raw data can’t answer your research question. The last step of designing your research is planning how you’ll analyse the data.

Quantitative data analysis

In quantitative research, you’ll most likely use some form of statistical analysis . With statistics, you can summarise your sample data, make estimates, and test hypotheses.

Using descriptive statistics , you can summarise your sample data in terms of:

- The distribution of the data (e.g., the frequency of each score on a test)

- The central tendency of the data (e.g., the mean to describe the average score)

- The variability of the data (e.g., the standard deviation to describe how spread out the scores are)

The specific calculations you can do depend on the level of measurement of your variables.

Using inferential statistics , you can:

- Make estimates about the population based on your sample data.

- Test hypotheses about a relationship between variables.

Regression and correlation tests look for associations between two or more variables, while comparison tests (such as t tests and ANOVAs ) look for differences in the outcomes of different groups.